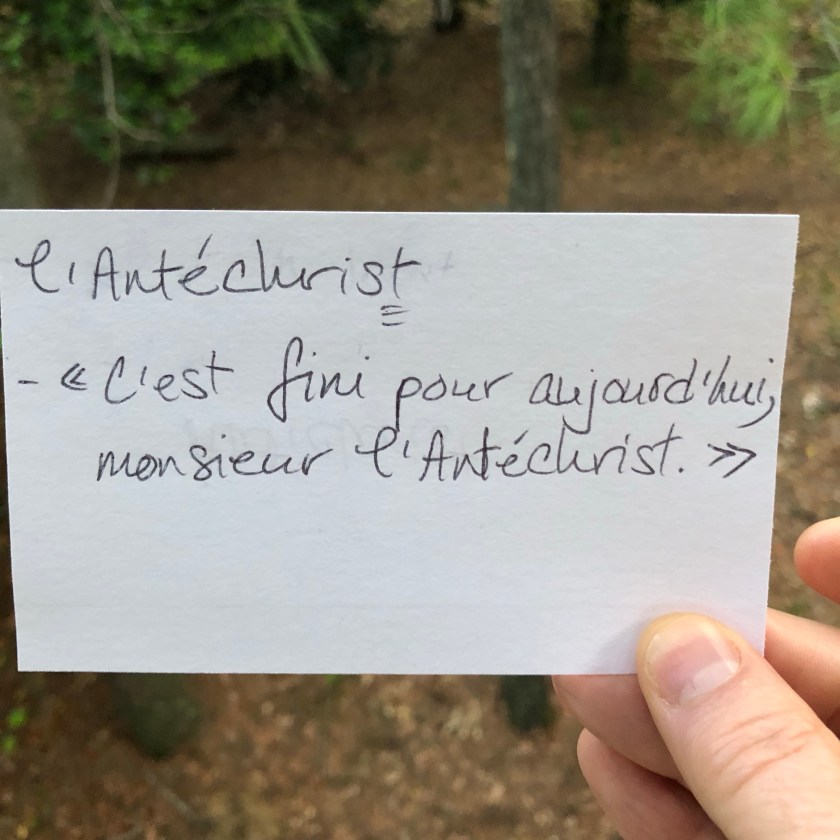

Camus’s L’Étranger, end of the first chapter of Part II: “that’s all for today, Mr. Antichrist.” Note that the final T is pronounced.

Camus’s L’Étranger, end of the first chapter of Part II: “that’s all for today, Mr. Antichrist.” Note that the final T is pronounced.

What computational linguists actually do all day: The debugging edition

We already knew that the patient had the primary, secondary, and tertiary stages of syphilis.

Tell someone you’re a computational linguist, and the next question is almost always this: so, how many languages do you speak? This annoys the shit out of us, in the same way that it might annoy a public health worker if you asked them how many stages of syphilis they have. (There are four. When I was a squid (military slang for “sailor”), one of our cardiologists lost her cool and threw a scalpel. It stuck in one of my mates’ hands. We already knew that the patient had the primary, secondary, and tertiary stages of syphilis, so my buddy was one unhappy boy…)

Being asked “how many languages do you speak?” annoys us because it reflects a total absence of knowledge about what we devote our professional lives to. (This is obviously a little arrogant–why should anyone else bother to find out about what we devote our professional lives to? That’s our problem, right? Nonetheless: the millionth time that you get asked, it’s annoying.) It’s actually easier to explain what linguistics is in French than it is in English, because French has two separate words for things that are both covered by the word language in English:

- une langue is a particular language, such as French, or English, or Low Dutch.

- le langage is language as a system, as a concept.

Linguists study the second, not the first. People who call themselves linguists might specialize in vowels, or in words like “the,” or in how people use language both to segregate themselves and to segregate others. Whatever it is that you do, you’re basing it on data, and the data comes from actual languages, so you might work with any number of them–personally, I wrote a book on a language spoken by about 30,000 people in what is now South Sudan. The point of that work, though, is to investigate broader questions about langage, more so than to speak another language–that’s a very different thing. I can tell you a hell of a lot about the finite state automata that describe tone/tone-bearing-unit mappings in that language, but can’t do anything in it beyond exchange polite greetings (and one very impolite leave-taking used only amongst males of the same age group).

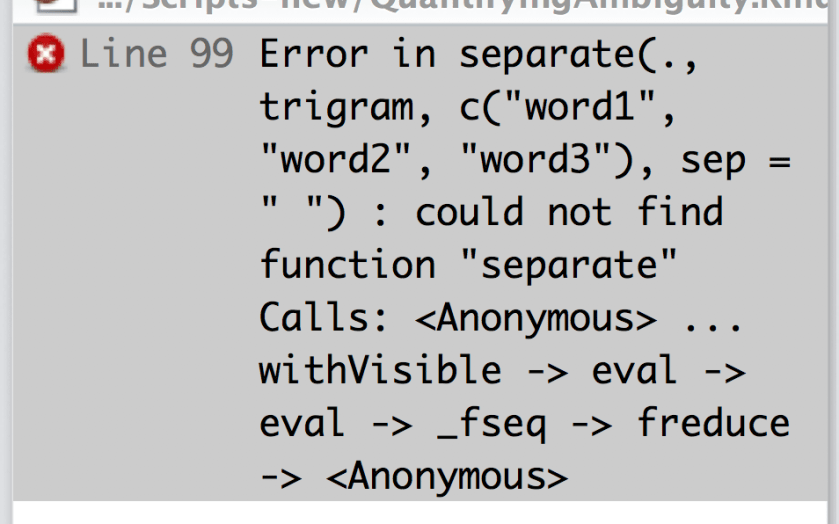

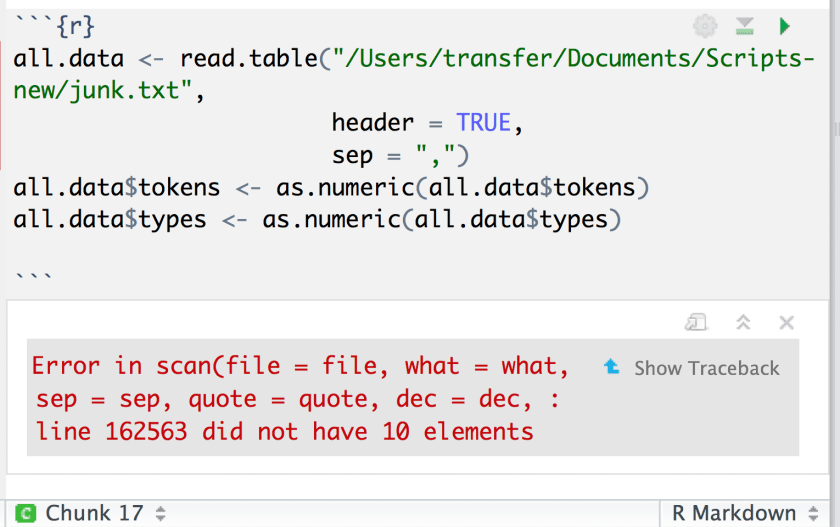

So, if you’re not spending your days sitting around memorizing vocabulary items in three different regional variants of Upper Sorbian, what does a linguist actually do all day? Here’s a typical morning. I was trying to do something with trigrams (3-word sequences–approximately the longest sequence of words that you can include in a statistical model of language before it stops doing what you want it to do), when I ran into this:

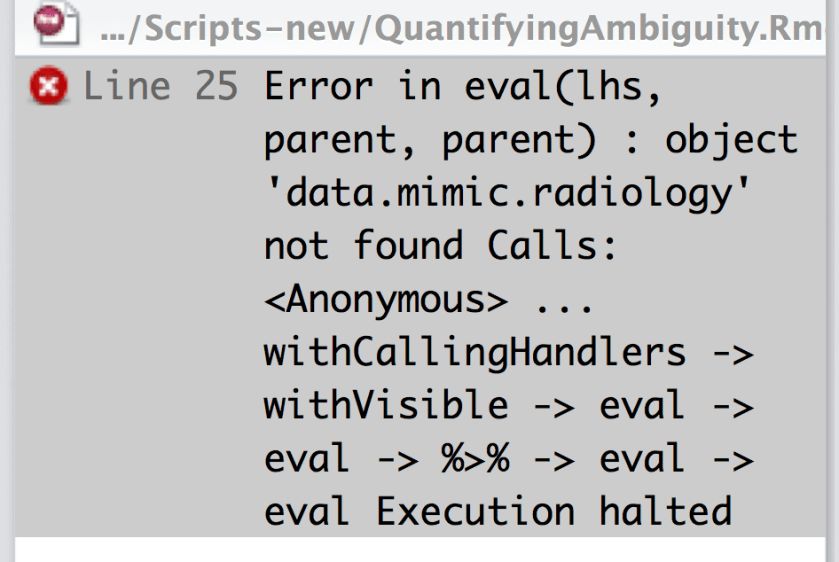

Fixed that one, and then there was a problem with my x-ray reports (my speciality is biomedical languages)…

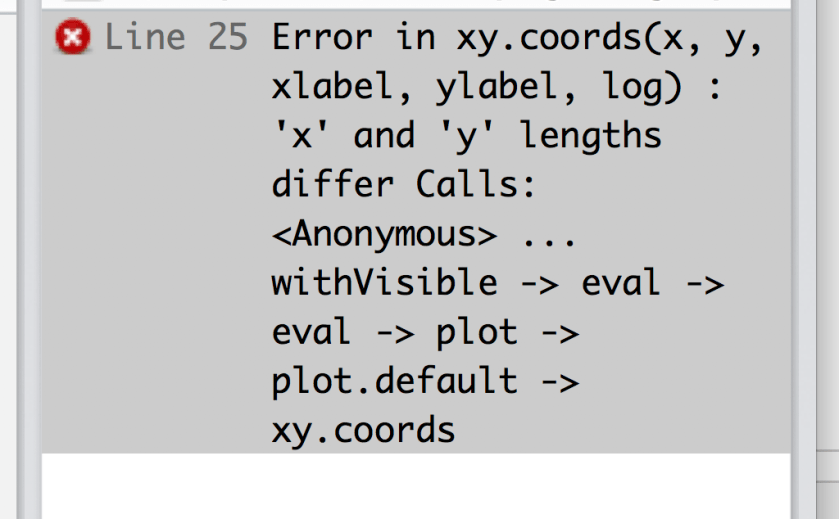

Fixed that one, and then…

…and your guess may well be better than mine on that one. God help you if you run into this kind of thing, though…

…because that message about not having some number of elements (a) usually takes forever to figure out, and then (b) once you do figure it out, reflects some kind of problem with your data that is going to give you a lot of headaches before you get it fixed.

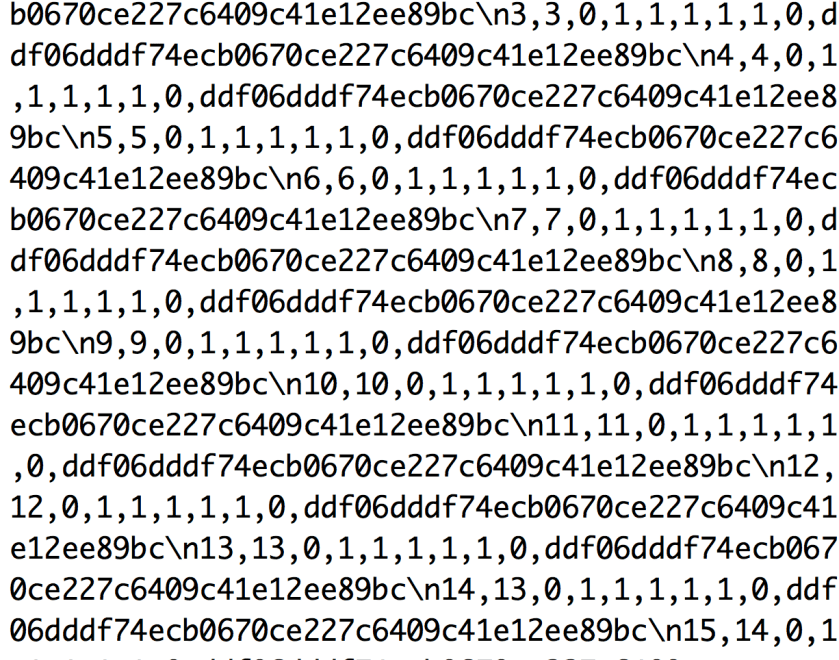

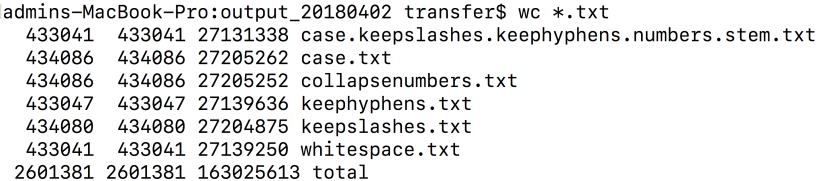

I spend a lot of my day looking at things like this:

.,..which is a bunch of 0s and 1s describing the relationship between word frequency and word rank, plus what goes wrong when your data gets created on an MS-DOS machine, which I will have to fix before I can actually do anything with said data (see the English notes below for what said data means); or this…

…which tells me some things about the effects of “minor” preprocessing differences on type/token ratios–they’re not actually so minor; or this…

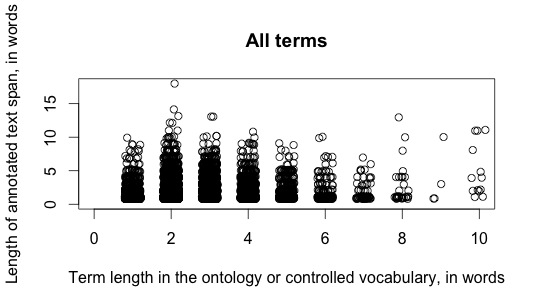

…which tells me that either there are some errors in that data, or there is an enormous amount of variability between the official terminology of the field and the way that said terminology actually shows up in the scientific literature. (See the leftmost blob–it indicates that there are plenty of cases of one-word terms that show up as more than 5 words in actual articles. That is certainly possible–disease in which abnormal cells divide without control and can invade nearby tissues is 13 words that together correspond to the single-word term cancer—but, I was surprised to see just how frequent those large discrepancies in lengths were. In my professional life, I love surprises, but they also suggest that you’d better consider the possibility that there are problems with the data.)

So, yeah: it’s not like I can’t get my hair cut in Japanese, or explain how to do post-surgical hand therapy in Spanish, or piss off a con artist in Turkish (a story for another time)–but, none of those have anything to do with my professional life as a computational linguist. That’s all about computing, which means computers, and I hate computers. Ironic, hein? Life is fucking weird, and I like it that way.

English notes

said: a shorter way of saying “the aforementioned.” Both of these are characteristic of written language, more so than of spoken language. Even in writing, though, it’s pretty bizarre if you’re not a native speaker, which is why I picked it to talk about today. A French equivalent would be ledit/ladite/lesdites (not sure about that last one–Phil dAnge?), which I have a soft spot for ’cause I learned it in Queneau’s Exercices de style.

Trying to think of helpful ways to recognize this bizarre usage of said, I went looking for examples of said whose part of speech is adjectival. Here are some of the things that I found:

- As such, any dispute that you may have on goods purchased or services availed of should be raised directly with said merchant/s.

- A seemingly endless shopping list to conquer, a shrinking budget with which to do said shopping ~ and let’s face it: our businesses don’t run themselves while we’re visiting relatives.

- This is a monumental pain in the ass — you don’t exactly trip over Notary Publics in today’s day and age — and I can only assume came from said company having a problem with identity once sometime in the last twelve years, and the president saying “fuck it.”

How it appears in the post:

- …what goes wrong when your data gets created on an MS-DOS machine, which I will have to fix before I can actually do anything with said data;…

- Either there are some errors in that data, or there is an enormous amount of variability between the official terminology of the field and the way that said terminology actually shows up in the scientific literature.

debugging: A technical term in software programming that refers to finding problems in your program. I used it in the title of today’s post because most of the illustrations that I gave of what I do all day are of irritating problems of one sort or another that I (really did) have to track down in the course of my day. They don’t tell you in school that tracking down such things are literally about 80% of what any programmer spends their time doing. Of course, any problem in a computer program is a problem that you created, so you can get irritated about them, but you most certainly cannot take your irritation out on anyone else…

American English listening practice: Mueller’s questions for Trump

A recording with a transcript is a great way to develop your oral comprehension skills. Here’s a link to a story on National Public Radio. It analyzes the recently released questions that the Justice Department wants to ask Donald Trump, the draft-dodging, give-secrets-to-the-Russians asshole who is the president of the United States–for the moment.

What Mueller’s Questions For President Trump Say About His Investigation – https://www.npr.org/607483451

Movement of bodies: the illustrated version

Fields, lexical and otherwise: Henry Reed’s sweetly funny WWII poem “Movement of bodies.”

As National Poetry Month draws to a close, here is more of the gentle humor of Henry Reed. This version of Movement of bodies, published in 1950, comes from the Sole Arabian Tree web site, where you can find a recording of Henry Reed reading the poem.

If you remember this one from last year: I’ve added some more explanations of the vocabulary, as well as some of your comments!

LESSONS OF THE WAR

III. MOVEMENT OF BODIES

Those of you that have got through the rest, I am going to rapidly

Devote a little time to showing you, those that can master it,

A few ideas about tactics, which must not be confused

With what we call strategy. Tactics is merely

The mechanical movement of bodies, and that is what we mean by it.

Or perhaps I should say: by them.

Strategy, to be quite frank, you will have no hand in.

It is done by those up above, and it merely refers to,

The larger movements over which we have no control.

But tactics are also important, together or single.

You must never forget that, suddenly, in an engagement,

You may find yourself alone.

This brown clay model is a characteristic terrain

Of a simple and typical kind. Its general character

Should be taken in at a glance, and its general character

You can, see at a glance it is somewhat hilly by nature,

With a fair amount of typical vegetation

Disposed at certain parts.

Here at the top of the tray, which we might call the northwards,

Is a wooded headland, with a crown of bushy-topped trees on;

And proceeding downwards or south we take in at a glance

A variety of gorges and knolls and plateaus and basins and saddles,

Somewhat symmetrically put, for easy identification.

And here is our point of attack.

But remember of course it will not be a tray you will fight on,

Nor always by daylight. After a hot day, think of the night

Cooling the desert down, and you still moving over it:

Past a ruined tank or a gun, perhaps, or a dead friend,

In the midst of war, at peace. It might quite well be that.

It isn’t always a tray.

And even this tray is different to what I had thought.

These models are somehow never always the same: for a reason

I do not know how to explain quite. Just as I do not know

Why there is always someone at this particular lesson

Who always starts crying. Now will you kindly

Empty those blinking eyes?

I thank you. I have no wish to seem impatient.

I know it is all very hard, but you would not like,

To take a simple example, to take for example,

This place we have thought of here, you would not like

To find yourself face to face with it, and you not knowing

What there might be inside?

Very well then: suppose this is what you must capture.

It will not be easy, not being very exposed,

Secluded away like it is, and somewhat protected

By a typical formation of what appear to be bushes,

So that you cannot see, as to what is concealed inside,

As to whether it is friend or foe.

And so, a strong feint will be necessary in this, connection.

It will not be a tray, remember. It may be a desert stretch

With nothing in sight, to speak of. I have no wish to be inconsiderate,

But I see there are two of you now, commencing to snivel.

I do not know where such emotional privates can come from.

Try to behave like men.

I thank you. I was saying: a thoughtful deception

Is always somewhat essential in such a case. You can see

That if only the attacker can capture such an emplacement

The rest of the terrain is his: a key-position, and calling

For the most resourceful manoeuvres. But that is what tactics is.

Or I should say rather: are.

Let us begin then and appreciate the situation.

I am thinking especially of the point we have been considering,

Though in a sense everything in the whole of the terrain,

Must be appreciated. I do not know what I have said

To upset so many of you. I know it is a difficult lesson.

Yesterday a man was sick,

But I have never known as many as five in a single intake,

Unable to cope with this lesson. I think you had better

Fall out, all five, and sit at the back of the room,

Being careful not to talk. The rest will close up.

Perhaps it was me saying ‘a dead friend’, earlier on?

Well, some of us live.

And I never know why, whenever we get to tactics,

Men either laugh or cry, though neither is strictly called for.

But perhaps I have started too early with a difficult task?

We will start again, further north, with a simpler problem.

Are you ready? Is everyone paying attention?

Very well then. Here are two hills.

English notes

This poem is full of delightful plays on multiple meanings of words, most of which I’ll skip to focus on the lexical field of geographic terms. Reed uses a bunch of terms that refer to elements of topography (Merriam-Webster: the art or practice of graphic delineation in detail usually on maps or charts of natural and man-made features of a place or region especially in a way to show their relative positions and elevations) as metaphors for a woman’s body. Many of these are terms that a typical native speaker (including myself) wouldn’t necessarily be able to define specifically, although I would guess that most people would at least know that they refer to elements of a terrain, and might even be able to group them into two classes: ones that refer to elevations (high points), and ones that refer to depressions (Merriam-Webster: a place or part that is lower than the surrounding area : a depressed place or part : hollow ). I’ll split them out in that way, then follow them with a few miscellaneous terms. (All links to Merriam-Webster are to the definition for that word.) For a reminder, here’s a paragraph from near the beginning of the poem:

Here at the top of the tray, which we might call the northwards,

Is a wooded headland, with a crown of bushy-topped trees on;

And proceeding downwards or south we take in at a glance

A variety of gorges and knolls and plateaus and basins and saddles,

Somewhat symmetrically put, for easy identification.

And here is our point of attack.

Elevations

knoll: Merriam-Webster: a small round hill : mound. The term grassy knoll, a small hill covered with grass, is closely associated with the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, particularly with conspiracy theories about it.

headland: Merriam-Webster: a point of usually high land jutting out into a body of water : promontory

plateau: Merriam-Webster: a usually extensive land area having a relatively level surface raised sharply above adjacent land on at least one side : tableland

Depressions

gorge: Merriam-Webster: a narrow passage through land; especially : a narrow steep-walled canyon or part of a canyon

basin: Merriam-Webster: a large or small depression in the surface of the land or in the ocean floor. As I speak a bit of French, it’s difficult not to make the association here with le bassin, the pelvis.

saddle: Merriam-Webster: a ridge connecting two higher elevations; a pass in a mountain range. In English, this has the same connections with sex as it does in French: J’en ai-t-y connu des lanciers, // Des dragons et des cuirassiers // Qui me montraient à me tenir en selle // A Grenelle!

Phil d’Ange points out that…

A few notes on some English/French topographical terms : “plateau” and “gorge” are exactly the same and have the same meanings . “Basin” is just one of the common English misspellings, here for “bassin” . But “un bassin” is also used in topography, not only to mean the pelvis, and is applied to large depressions . In France you have “le bassin parisien” and “le bassin aquitain”, rather wide surfaces . On the other hand we have nothing like a saddle in topography . “Une selle” is never used in that way, and I’d add that it is not related to sex either, except in specific occasions like the old song you quote . There are other words associated to horse riding that are common about sexual activities : monter, chevaucher, etc…

Others

wooded: Merriam-Webster: covered with growing trees

engagement: In the context of the poem, the most obvious meaning is the military one of a hostile contact between enemy forces (Merriam-Webster). Presumably Reed is also playing here on the more commonly-used meaning of a commitment to marriage (my best guess on all of the crying trainees).

You must never forget that, suddenly, in an engagement,

You may find yourself alone.

The French cognate has a much wider range of uses/meanings than the American English word. As Phil d’Ange puts it:

A word about “engagement, a French word that has the same meanings : military and commitment to any activity with a moral virtue : social, political, humanitary causes and for some weird reason to marriage (I guess it can be a humanitary cause in some cases) . Seriously “un engagement” is also a promise, a commitment to any act, moral or not : “Il a pris l’engagement de réparer ma voiture avant lundi”, “… l’engagement de me prêter 1000 €” . And it also means hiring an employee . “Engager” a housemaid, an accountant, a bodyguard ( that’s my daily life ha ha ) .

The situation seems to be different in the United Kingdom, where the range of meanings/uses of engagement is closer to that of French. Osyth put it this way:

We use engage in that way too …. I would ‘engage’ a butler or a garage to fix my car and I might be ‘engaged’ to do a piece of work for a magazine. When a couple is preparing for marriage they are ‘engaged’ which makes it alarming or appropriate depending on your feelings about the marital state (or more likely your own experience) that we also engage in combat!

tactics versus strategy: tactics are short-term–a tactical nuclear weapon is one that you would use on the battlefield. (Not very fun to think about, is it? When I tell people that some aspects of the peacetime military seem kinda silly and they ask me for examples, I always tell them about our “what to do in case of nearby nuclear weapon explosion” drills.) In contrast, strategic nuclear weapons are meant for the bigger picture–the stuff that you would use to hammer the other guy’s country in such a way that he becomes unable to continue fighting at all. My tactics in my professional life mostly consist of making schedules to ensure that I don’t miss deadlines, while my strategy is the set of papers that I plan to publish in the next few years. From the poem:

Strategy, to be quite frank, you will have no hand in.

It is done by those up above, and it merely refers to,

The larger movements over which we have no control.

But tactics are also important, together or single.

You must never forget that, suddenly, in an engagement,

You may find yourself alone.

to be at peace: “Calm and serene. My daughter was miserable all week, but she’s at peace now that her tests are over.” (TheFreeDictionary.com)

How Reed uses it in the poem (quite brilliantly):

After a hot day, think of the night

Cooling the desert down, and you still moving over it:

Past a ruined tank or a gun, perhaps, or a dead friend,

In the midst of war, at peace.

to fall out: in a military context, the most common meaning of this is to leave one’s place in the ranks (Merriam-Webster). From the Military.com web site:

Fall out

The command is “Fall Out.” On the command, you may relax in a standing position or break ranks (move a few steps out of formation). You must remain in the immediate area, and return to the formation on the command “Fall In.” Moderate speech is permitted.

How it appears in the poem:

I think you had better

Fall out, all five, and sit at the back of the room

Judging distances: the illustrated version

More wistful beauty from Henry Reed’s WWII poetry.

I can remember it like it was yesterday: being a teen-ager, barely turned 18 (at the time, you could enlist at 17, and I did), lying in my bunk on a guided missile cruiser off of the coast of someplace or other. Thinking: if only I could go back and finish high school… National Poetry Month is not National Poetry Month without Henry Reed’s wistful beauty. His meditation on time and the way that some times can be much farther away — or closer — than others in Judging Distances always takes me back to my misguided youth and that rack (bunk) on the USS Biddle. I got this version of the poem from the Sole Arabian Tree web site; at the bottom of their page, you can find a link to a recording of it. After the text, you’ll find a couple of notes on the vocabulary.

LESSONS OF THE WAR, by Henry Reed

Published 1943

II. JUDGING DISTANCES

Not only how far away, but the way that you say it

Is very important. Perhaps you may never get

The knack of judging a distance, but at least you know

How to report on a landscape: the central sector,

The right of the arc and that, which we had last Tuesday,

And at least you know

That maps are of time, not place, so far as the army

Happens to be concerned—the reason being,

Is one which need not delay us. Again, you know

There are three kinds of tree, three only, the fir and the poplar,

And those which have bushy tops to; and lastly

That things only seem to be things.

A barn is not called a barn, to put it more plainly,

Or a field in the distance, where sheep may be safely grazing.

You must never be over-sure. You must say, when reporting:

At five o’clock in the central sector is a dozen

Of what appear to be animals; whatever you do,

Don’t call the bleeders sheep.

I am sure that’s quite clear; and suppose, for the sake of example,

The one at the end, asleep, endeavors to tell us

What he sees over there to the west, and how far away,

After first having come to attention. There to the west,

On the fields of summer the sun and the shadows bestow

Vestments of purple and gold.

The still white dwellings are like a mirage in the heat,

And under the swaying elms a man and a woman

Lie gently together. Which is, perhaps, only to say

That there is a row of houses to the left of the arc,

And that under some poplars a pair of what appear to be humans

Appear to be loving.

Well that, for an answer, is what we rightly call

Moderately satisfactory only, the reason being,

Is that two things have been omitted, and those are very important.

The human beings, now: in what direction are they,

And how far away, would you say? And do not forget

There may be dead ground in between.

There may be dead ground in between; and I may not have got

The knack of judging a distance; I will only venture

A guess that perhaps between me and the apparent lovers,

(Who, incidentally, appear by now to have finished,)

At seven o’clock from the houses, is roughly a distance

Of about one year and a half.

English notes

knack: “an ability, talent, or special skill needed to do something” (Merriam-Webster). You “have” a (or the) knack “for” doing something, after you “get” a (or the) knack “for” doing it–you learn it. Merriam-Webster gives a list of synonyms for knack:

aptitude, bent, endowment, faculty, flair, genius, gift, head, talent

…and then gives a wonderful discussion of them that does a nice job of making the point that there aren’t really any synonyms:

gift, faculty, aptitude, bent, talent, genius, knack mean a special ability for doing something. gift often implies special favor by God or nature.

- ⟨the gift of singing beautifully⟩

faculty applies to an innate or less often acquired ability for a particular accomplishment or function.

- ⟨a faculty for remembering names⟩

aptitude implies a natural liking for some activity and the likelihood of success in it.

- ⟨a mechanicalaptitude⟩

bent is nearly equal to aptitude but it stresses inclination perhaps more than specific ability.

- ⟨a family with an artistic bent⟩

talent suggests a marked natural ability that needs to be developed.

- ⟨has enough talent to succeed⟩

geniussuggests impressive inborn creative ability.

- ⟨has no greatgenius for poetry⟩

knack implies a comparatively minor but special ability making for ease and dexterity in performance.

- ⟨the knack of getting along⟩

Knack appears in the poem twice–in the beginning:

Perhaps you may never get

The knack of judging a distance, but at least you know

How to report on a landscape

…and then in those stunning last lines:

I may not have got

The knack of judging a distance; I will only venture

A guess that perhaps between me and the apparent lovers,

(Who, incidentally, appear by now to have finished,)

At seven o’clock from the houses, is roughly a distance

Of about one year and a half.

barn: “a building used for storing grain and hay and for housing farm animals” (Merriam-Webster) Merriam-Webster gives an obscure definition of barn that I have never, ever come across before: : a unit of area equal to 10−24 square centimeters that is used in nuclear physics for measuring cross section.

As broad as a barn door is an analogy used to describe something that is very wide. The most common thing to describe as being broad as a barn door is someone’s ass, and that’s not typically a compliment. Looking for examples on the Sketch Engine web site, I see very few uses of broad as a barn door that are not negative. (You’ll also see big as a barn door and wide as a barn door. Why miss the opportunity for some alliteration?)

- I had my first look at the boom horse Hay List . He’s built like a tank with a backside as big as a barn door.

- And since security companies advise against “unsubscribing” from spam, since to most spammers, this merely means the address is active, the hole in the law is as wide as a barn door.

- I have sent you a cheque for what you asked, you are very modest in your request for which I like you all the better; a Colonist would have opened his mouth as wide as a barn door.

- Now, for Europe, this means we have to absolutely cancel the EU Treaties from Maastricht to Lisbon, we have to return to national currencies, and we have to establish, simultaneously, a global Glass-Steagall Act, and I mean the real Glass-Steagall as Franklin D. Roosevelt imposed it, and not some watered-down versions like the Vickers Commission ring-fencing, or Volcker Rule, which leave holes for banking speculation as big as a barn door.

- But the chain remained tangled, and amid all kinds of mocking advice we drifted down upon and fouled the Ghost, whose bowsprit poked square through our mainsail and ripped a hole in it as big as a barn door.

I love that the drill instructor tells the new recruits not to call a barn a barn, but doesn’t tell them what they should call it:

A barn is not called a barn, to put it more plainly,

Or a field in the distance, where sheep may be safely grazing.

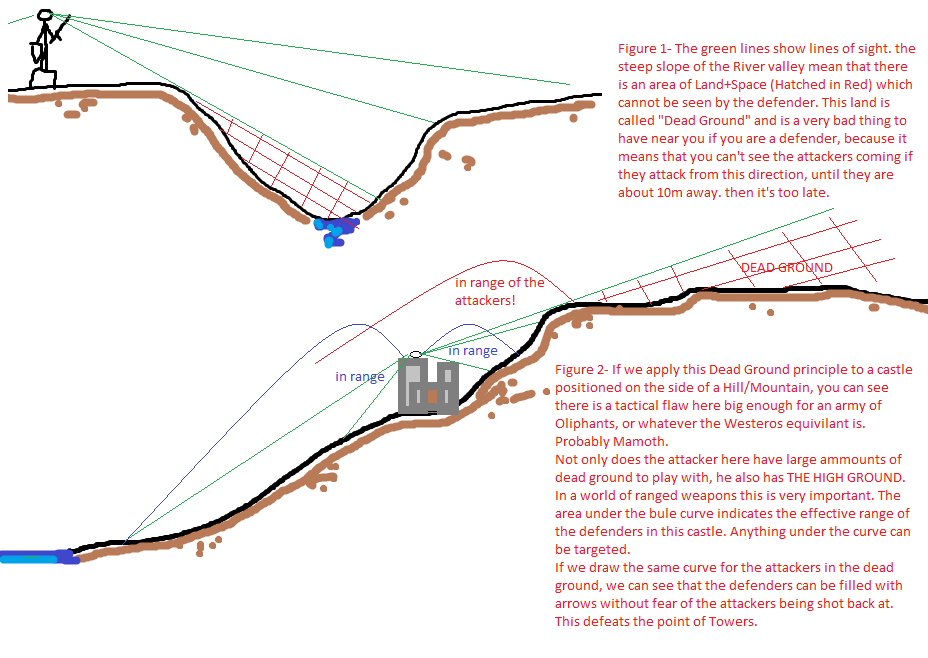

dead ground: technically, this is space that cannot be observed. Tracing back through references, it seems to have come from a term for describing parts of the base of a castle’s fortifying walls that were sheltered from fire by the defenders, and therefore were weak points vulnerable to attack. Here’s one Quora writer’s definition of it:

Dead Ground is when the observer is unable to resolve keeping eyes on over an intermediate part of the stretch of ground being observed. The observer may be interchanged with detection equipment and includes areas of surveillance which are obscured from a clear alarm signature (environmental distortion from clear auditory reception) or trigger reception (automatic pixel motion detection) by the way the observer is angled. Dead ground exists in hidden embankments and undulating paths, roads or desert open areas with heat waves rising and obscuring or creating distorted imagery.

Some examples from the enTenTen corpus, searched via the Sketch Engine web site:

- Small valleys and dead ground permitted the enemy to approach without being observed.

- Bravo started firing at the antiaircraft gun with small-arms, this almost proved fatal, as their target immediately cut loose in retaliation, luckily for Bravo they were in dead ground , and the hail of fire passed harmlessly overhead , as the Swapo gunners could not depress their gun sufficiently, yet it was a sobering experience.

“Dead ground” shows up twice in the poem, both towards the aforementioned stunning last lines:

The human beings, now: in what direction are they,

And how far away, would you say? And do not forget

There may be dead ground in between.

There may be dead ground in between; and I may not have got

The knack of judging a distance; I will only venture

A guess that perhaps between me and the apparent lovers,

(Who, incidentally, appear by now to have finished,)

At seven o’clock from the houses, is roughly a distance

Of about one year and a half.

Loving a woman with a broken nose

Like loving a woman with a broken nose, you may well find lovelier lovelies. But never a lovely so real. — Nelson Algren

Like loving a woman with a broken nose, you may well find lovelier lovelies. But never a lovely so real. — Nelson Algren, Chicago: City on the Make (1951)

I have never managed to translate these lines from Nelson Algren’s (book-length) prose poem Chicago: City on the Make to French to my satisfaction. The problem comes from the fact that lovely can (and usually is) an adjective, but can also be — super-rarely, I suspect — a noun. Hmmm–not unlike belle in French, maybe? Native speaker Phil d’Ange came up with this classical couplet:

To keep the rhyme but also to have the same number of syllables, a must in French classical poetry, I made two 12-foot verses (the top of classicism, what we call “des alexandrins”, 12 foot verses with “la césure à l’hémistiche” i.e. a natural pause right in the middle, after 6 feet) that keep the meaning and the rhyme.

“Peut-être verras-tu un jour belles plus belles

Mais jamais ne verras de belle plus réelle” .

Nelson was talking here about Chicago, but Chicago was not his only love: Simone de Beauvoir was another. The end of their relationship is typically portrayed as her leaving him to return to Jean-Paul Sartre, but I am not entirely convinced. Here is an excerpt from a letter that she wrote to him in 1950, when he had pulled back from her, dissatisfied with the relationship.

I am not sad. Rather stunned, very far away from myself, not really believing you are now so far, so far, you so near. I want to tell you only two things before leaving, and then I’ll not speak about it any more, I promise. First, I hope so much, I want and need so much to see you again, some day. But, remember, please, I shall never more ask to see you — not from any pride since I have none with you, as you know, but our meeting will mean something only when you wish it. So, I’ll wait. When you’ll wish it, just tell. I shall not assume that you love me anew, not even that you have to sleep with me, and we have not to stay together such a long time — just as you feel, and when you feel. But know that I’ll always long for your asking me. No, I cannot think that I shall not see you again. I have lost your love and it was (it is) painful, but shall not lose you. Anyhow, you gave me so much, Nelson, what you gave me meant so much, that you could never take it back. And then your tenderness and friendship were so precious to me that I can still feel warm and happy and harshly grateful when I look at you inside me. I do hope this tenderness and friendship will never, never desert me. As for me, it is baffling to say so and I feel ashamed, but it is the only true truth: I just love as much as I did when I landed into your disappointed arms, that means with my whole self and all my dirty heart; I cannot do less. But that will not bother you, honey, and don’t make writing letters of any kind a duty, just write when you feel like it, knowing every time it will make me very happy.

Well, all words seem silly. You seem so near, so near, let me come near to you, too. And let me, as in the past times, let me be in my own heart forever.

Your own Simone

In lieu of English (or French) notes, here’s some linguistics geekery to ruin your day (or, at a minimum, Algren’s poetry).

In this post, I introduced an intuition without actually backing it up:

The problem comes from the fact that lovely can (and usually is) an adjective, but can also be — super-rarely, I suspect — a noun.

How could one know whether or not it’s the case that it’s quite rare for lovely to be an adjective? Data, data, data.

I went to the Sketch Engine web site, where one can find all manner of corpora (pre-analyzed sets of linguistic data), as well as a nice interface for searching them. (No, they don’t pay me to shill for them–I pay a pretty penny for access to the site, which I use in my actual research.) I picked a corpus (the singular of corpora) called the enTenTen13 corpus. It contains a bit under 20 billion words of English from various and sundry sources, mostly scraped off of the web. The analysis that’s been done on this data consisted of using a computer program to “tag” the lexical categories (parts of speech to those civilians amongst you) of all of the words in it.

With that data, and a tool that will let me specify the part of speech for which I’m looking, I can do two separate searches:

- lovely as an adjective

- lovely as a noun

Why two searches? I wanted to know whether it’s rare for lovely to be a noun, so why didn’t I just search for lovely as a noun? Because numbers by themselves aren’t really meaningful: to know if a number–in this case, the frequency of lovely occurring as a noun–is large or small (why didn’t I say big or little? see previous posts about how there aren’t really any synonyms), I need to compare it to something else–in this case, to the frequency of some other word/lexical category. Which word, with which lexical category? Well, lovely as an adjective makes as much sense as anything else, so I did that.

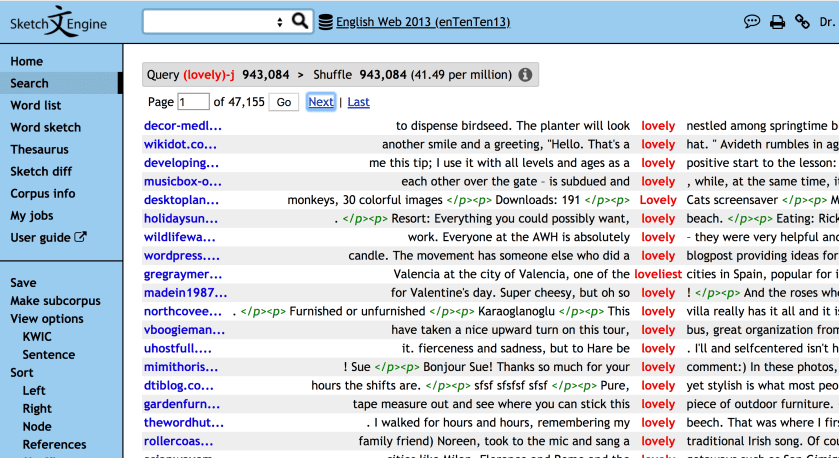

Here’s what I got when I searched for lovely as an adjective. Notice that in the upper-left corner of the white-background panel, it says Query (lovely)-j: the “j” means adjective (for reasons that we need not get into, but it’s obvious enough to someone in the field that the Sketch Engine folks clearly didn’t see any need to explain it). You may be wondering: what about lovelier or loveliest? Gotcha covered–I actually did the search not for the “word” lovely, but for the “lemma” lovely, which means that the program is also looking for loveliest (you can see that it found an example of that, about halfway down the list)–and Lovely, Lovelier, and any other form with capital letters (and found one, 5 down from the top). The program found 943,084 tokens of lovely (or, more precisely, of the lemma lovely); we don’t know whether 943,084 is a lot or a little (remember the Best Movie Line Ever: 5 inches is a lot of snow, and it’s a TREMENDOUS amount of rain, but it’s not very much dick), but pas de souci, Sketch Engine does the math to convert that into a frequency: 41.49 occurrences per million words (see the gray bar (or grey if you’re a Brit) at the top of the white panel.

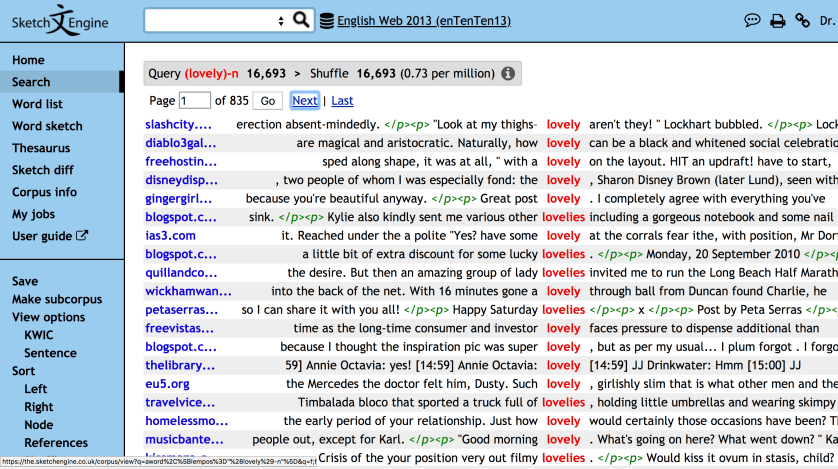

With a frequency for lovely as an adjective to which I can now compare the frequency of lovely as a noun, I did another search. This time, I looked for the lemma lovely, but as a noun. 6th from the top, you’ll see it pluralized–Kylie also kindly sent me various other lovelies including a gorgeous notebook… …and if you’re pluralized and in you’re in English, then you’re not an adjective. The frequency of lovely as a noun? Sketch Engine tells me that it’s 0.73 times per million words.

So, I get the following frequencies:

- lovely as an adjective: 41.49 occurrences per million words

- lovely as a noun: 0.73 occurrences per million words

41.49 is about 42 times 0.73, so indeed, lovely as a noun seems to be pretty fucking rare: my intuition has been supported by the quantitative data.

Now, I know what you’re thinking: Zipf, your computer program sucks–a LOT of the times that it thought that lovely was a noun, it was ACTUALLY an adjective:

- Look at my thighs–lovely aren’t they! (first line)

- Naturally, how lovely can be a black and whitened celebration… (second line)

Point number one: it’s not that it sucks–it’s that it makes mistakes. If there is a computer program that works with language and does not make mistakes, I have never heard of it, and a priori wouldn’t believe it if someone said that one existed. The question is: what kinds of mistakes does it make, and what can we learn from them?

- It’s making a frequent mistake of thinking that the adjective is a verb. It doesn’t have to be that way, right? It could have been the other way around.

- The mistake that we saw in (1) is a general one: it is too often judging the word to belong to the category to which it belongs most frequently. This is the typical pattern with any computer program that does things with language: when something is ambiguous, computer programs tend to be biased towards the most common “interpretation.”

- Therefore, when we look at the frequency of lovely as a noun, we know that it’s probably an over-estimate. Doesn’t have to be that way, right? We could just as well have gotten an under-estimate. But, since we’re looking at the less-frequent category here, and the program tends to erroneously assign the more-frequent category, we know that we should adjust our estimate of the frequency of lovely as a noun downwards.

Implicit in all three of these observations: in general, we are not getting frequencies of things–we are getting estimates of frequencies, where the difference between the estimate and the truth is affected by a lot of things, including how well the sample represents the world as a whole, the errors in our measuring instruments (in this case, the program that assigned the lexical categories, etc.

…and now, having undoubtedly sucked all of the joy out of Algren’s wonderful words–they’ve stuck with me since I was a teenager, but I’ve probably ruined them for you forever–I will head down to the Office française de l’immigration et de l’intégration–OFII, as we expats call it–to get my carte de séjour, and leave you to curse me. Feel free to post your own poems–it is, after all, National Poetry Month…

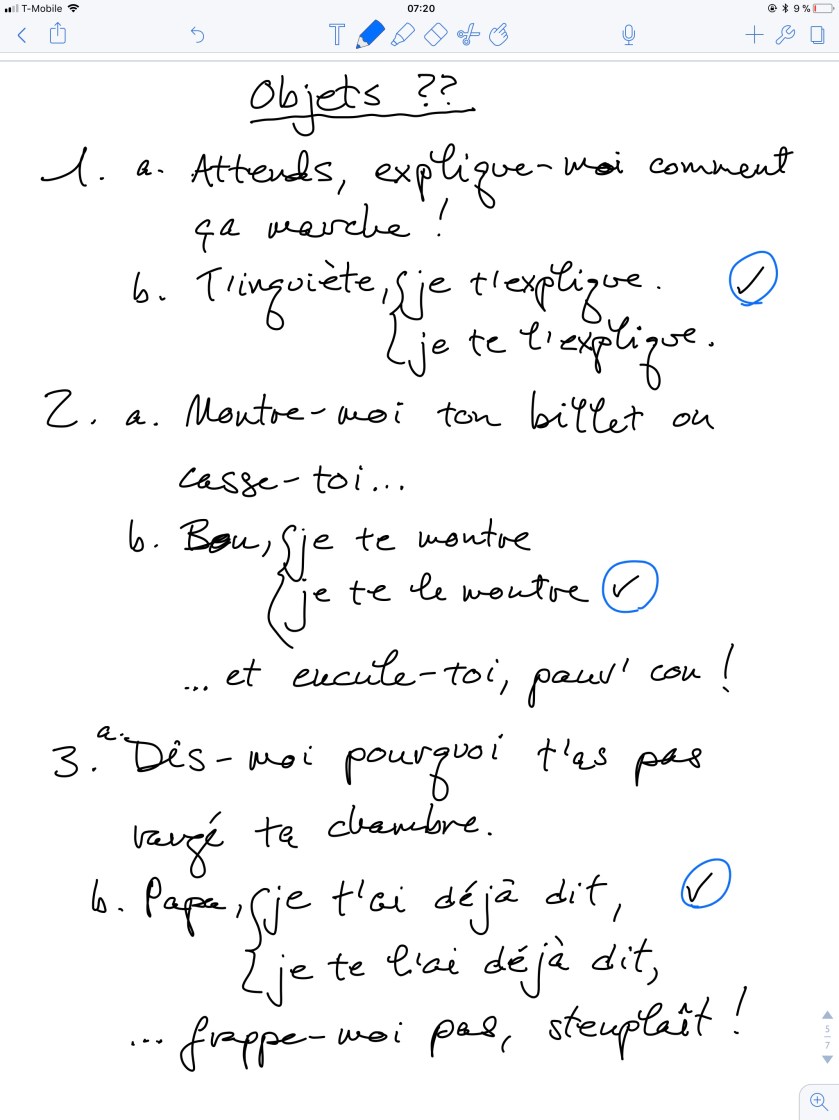

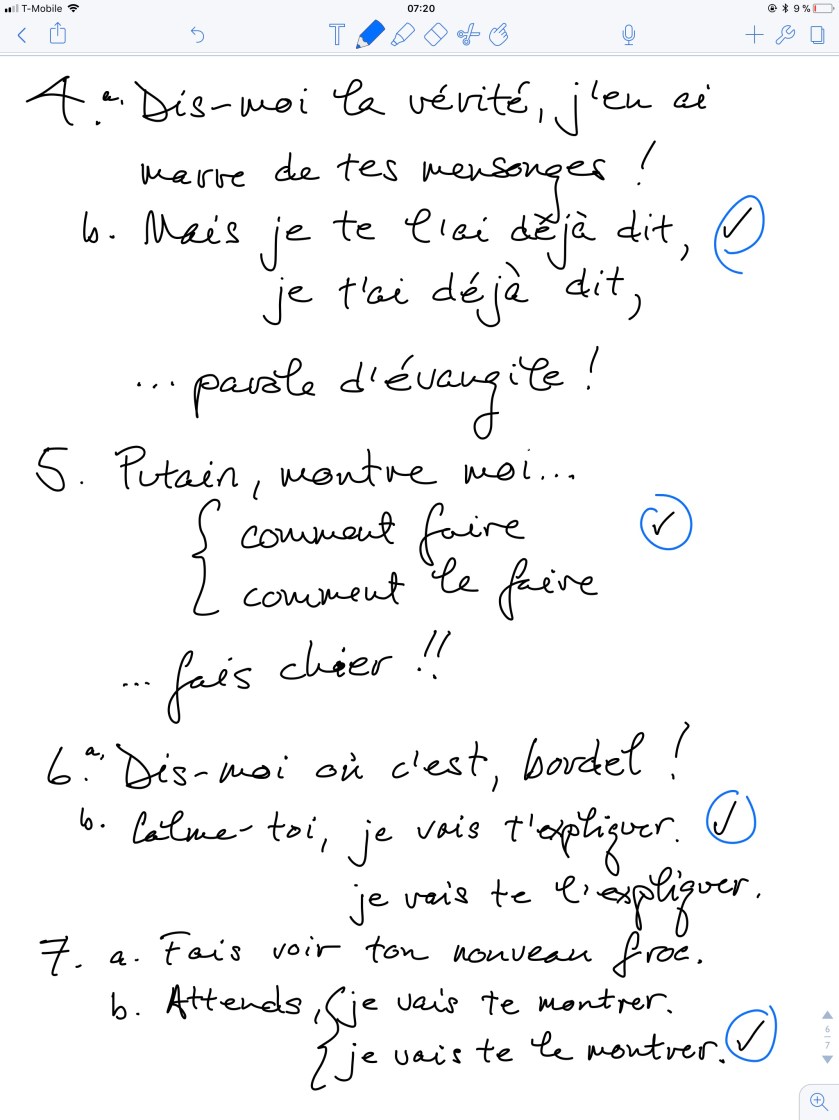

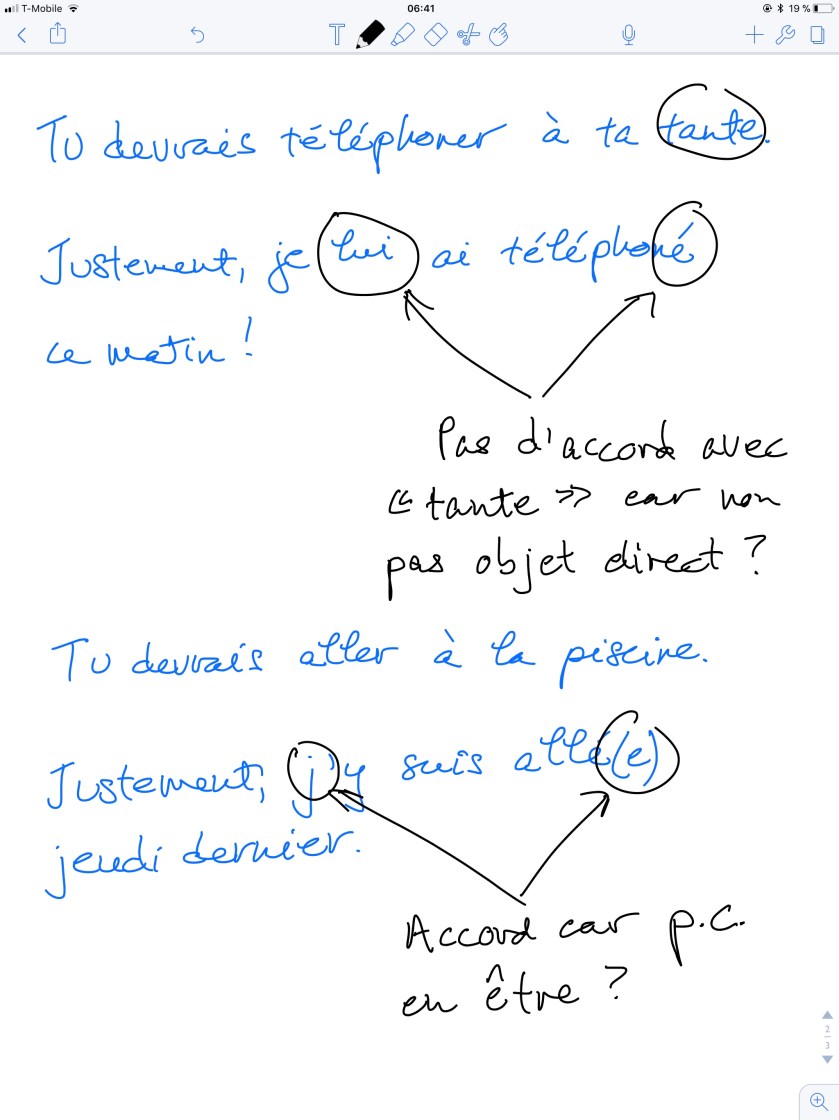

Objects, or not? Corrections appreciated…

Sometimes it all just gets a little too abstract for me…

Native speakers: my problem here is when there should be a direct object in these sentences, and when there shouldn’t. Your corrections to my guesses would be much appreciated!

Just trying to figure things out…

Hallelujah

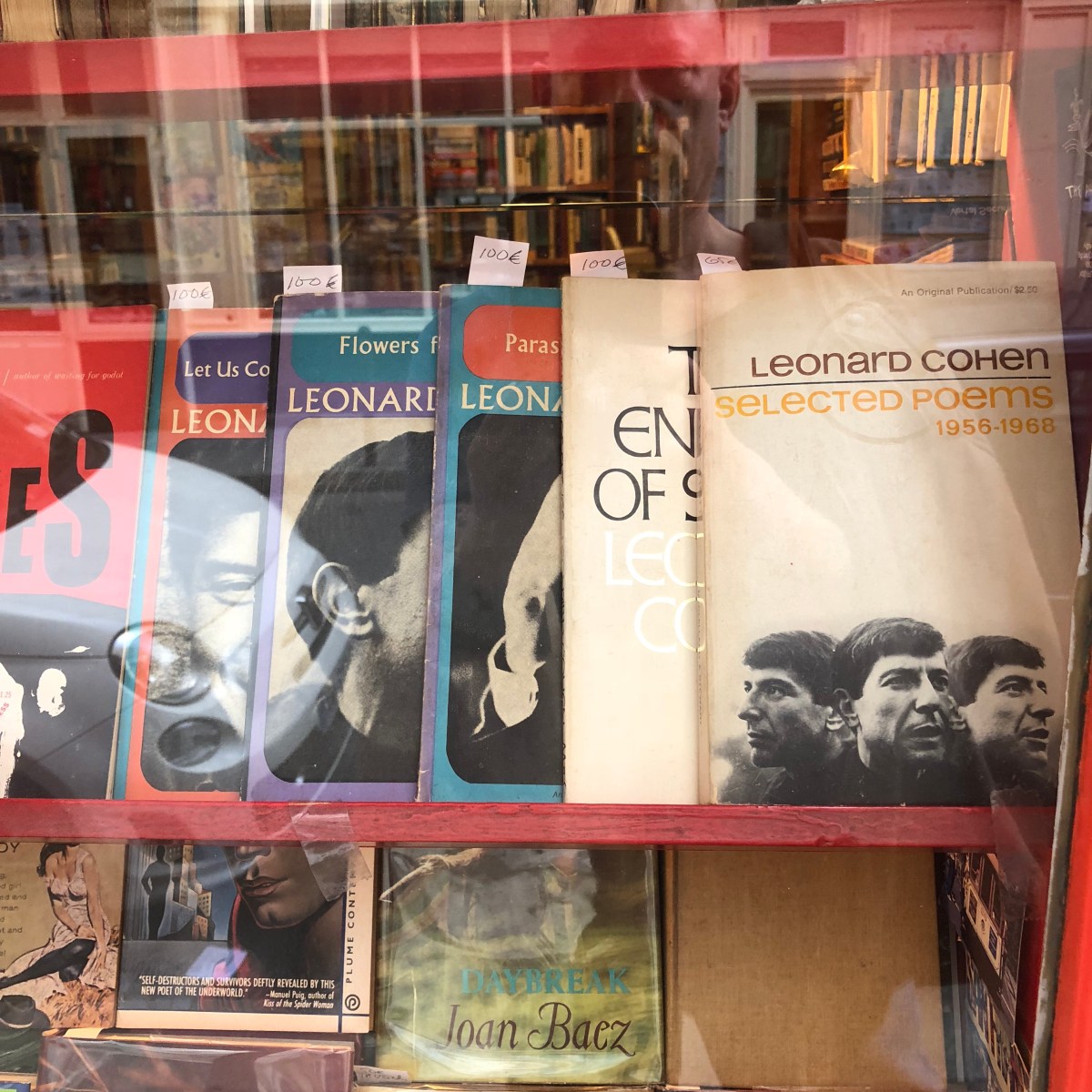

Songs, poetry, Leonard Cohen, Hallelujah, an Iranian prison, and Trump.

I once heard an interview on NPR with Maziar Bahari, a Persian-Canadian guy who got thrown in jail in Iran and stayed there for quite a while, being abused in the ways that Persian-North-Americans get abused in Iranian jails. It’s not pretty. Something that struck me: he said that he kept himself sane through the ordeal by singing Leonard Cohen songs in his head.

Every year I post poems for National Poetry Month, and every year I ask myself the same question: do song lyrics count as poetry? It’s not an easy question to answer. In order to answer it, you have to define what poetry is, but you also have to define what a song is, and that’s not as easy as you might think, either. For example: the most famous poem in Old English is Beowulf. But, scholars widely agree that it was probably sung, not recited. Phil d’Ange recently talked about the lyricists of the French chanson réaliste with respect to this question:

Aristide Bruant was the archetype of a very Parisian species, “les chansonniers”, late 1800s-early 1900s. The center of these song makers (who could also be singers) was more Montmartre (the famous Chat Noir) or the “guinguettes” along the Marne river than Grenelle. In a way these chansonniers were the descendants of the troubadours, the Greek aedes, a very old tradition. Of course they liked to mix slang and classical, sexual or political hints and word plays. … Chansonniers are not from the same level [as poets]. Gainsbourg once famously said that he was doing “un art mineur”, as opposed to poetry, classical music, theatre, etc … We could say the same thing, chansonniers did “un art mineur”. And they were not always poets: often they played with words, double-meanings, easily sexual or political about their time, there were many sorts of productions coming from them. [They] were practicing a quintessentially Parisian attitude, linked to all the provocation that the Parisian working classes provided to the world, from humour to revolutions. And some poetry too. I tell you, what you see and know is not Paris, Paris needed its working class inside the city, without this the splendid painters and writers who came from every country to work in Paris would not have been able to afford a hotel and a life there . And there would not have been any of the several French revolutions.

So, how are we to think about Beowulf–as the poem as which we read it, or as the … whatever it was as which it was sung? And must we think of Higelin as a singer, not as a poet, even when he is (as far as I can tell) reciting his insanely wonderful stuff?

So, yeah: this is the question into which a lot of my mental energy goes during April, the US National Poetry Month. An bigoted asshole opposed to American values rules the White House; the UK is poking a hole in the only organization that has kept Western Europe at peace for a generation since…well, has Western Europe ever been at peace for this long before?; the Front National got 1/3 of the vote in the 2017 French presidential election, and I’m putting my mental energy into definitional questions about music and poetry. Enough!

A walk through the St. Germain-des-Prés neighborhood of Paris the other day brought me to the San Francisco Book Company, a delightful little anglophone used book store on the rue M. le Prince. In the window, I saw the collection of books whose photograph you see above: Leonard Cohen: Collected Poems. Leonard Cohen is (was–he recently died) the much-beloved singer/songwriter whose songs kept that poor Persian-Canadian guy sane through the tortures of an Iranian prison. Is his stuff the lyrics of a song if he releases them on an album, but the words of a poem if he doesn’t? If he publishes them in a book now, and then records them later, do they start as a poem, but then later turn into a song? I elect to solve my problem this way: if they’re words–shit, if they are, or could be, sounds produced by the human vocal apparatus–I’m going to enjoy them for National Poetry Month, and honi soit qui mal y pense. (Or, as we linguists like to say: honi schwa qui mal y pense, but that’s a joke for another time.)

So, for today’s little bit of National Poetry Month, here’s one of Leonard Cohen’s best-loved songs pieces: Hallelujah. Seulement voilà, I’m going to give you my favorite version of it–in Yiddish. It is most definitely not an exact translation, but I think that it captures the feeling of the original pretty nicely. The English translation of the Yiddish words are given in the subtitles to the video, and below that I’ll post the Yiddish version in Yiddish writing and transcribed in what’s known as the YIVO Yiddish orthography in the Latin alphabet–just know that kh is the sound of the r in paître (oh, how I love an excuse to use that verb–I wish to hell I could conjugate it) and you’ve mostly got it. Enjoy, and may Leonard Cohen give us the strength to survive Trump that he gave Maziar Bahari to survive torture in an Iranian prison.

„הללויה‟ פֿון לענאָרד כּהן אויף ייִדיש

(איבערגעזעצט פֿון דניאל קאַהן; מיט דער הילף פֿון דזשאַש וואַלעצקי, מענדי כּהנא און מיישקע אַלפּערט)

געווען אַ ניגון ווי אַ סוד

וואָס דוד האָט געשפּילט פֿאַר גאָט

נאָר דיר וואָלט׳ס נישט געווען אַזאַ ישועה

מע זינגט אַזוי: אַ פֿאַ, אַ סאָל

אַ מי שברך הייבט אַ קול

דער דולער מלך וועבט אַ הללויה

דײַן אמונה איז געוואָרן שוואַך

בת שבֿע באָדט זיך אויפֿן דאַך

איר חן און די לבֿנה דײַן רפֿואה

זי נעמט דײַן גוף, זי נעמט דײַן קאָפּ

זי שנײַדט פֿון דײַנע האָר אַ צאָפּ

און ציט פֿון מויל אַראָפּ אַ הללויה

אָ טײַערע איך קען דײַן סטיל

איך בין געשלאָפֿן אויף דײַן דיל

כ׳האָב קיינמאָל נישט געלעבט מיט אַזאַ צנועה

און איך זע דײַן שלאָס, איך זע דײַן פֿאָן

אַ האַרץ איז נישט קיין מלכס טראָן

ס׳איז אַ קאַלטע און אַ קאַליע הללויה

אוי ווי אַמאָל, טאָ זאָג מיר אויס

וואָס טוט זיך דאָרטן אין דײַן שויס

טאָ וואָס זשע דאַרפֿסט זיך שעמען ווי אַ בתולה

און געדענק ווי כ׳האָב אין דיר גערוט

ווי די שכינה גלוט אין אונדזער בלוט

און יעדער אָטעם טוט אַ הללויה

זאָל זײַן מײַן גאָט איז גאָר נישטאָ

און ליבע זאָל זײַן כּל מום רע

אַ פּוסטער טרוים צעבראָכן און מכולה

נישט קיין געוויין אין מיטן נאַכט

נישט קיין בעל־תּשובֿה אויפֿגעוואַכט

נאָר אַן עלנטע קול־קורא הללויה

אַן אַפּיקורס רופֿסטו מיך

מיט שם־הוויה לעסטער איך

איז מילא, איך דערוואַרט נישט קיין גאולה

נאָר ס׳ברענט זיך הייס אין יעדן אות

פֿון אַלף־בית גאָר ביזן סוף

די הייליקע און קאַליע הללויה

און דאָס איז אַלץ, ס׳איז נישט קיין סך

איך מאַך דערווײַלע וואָס איך מאַך

איך קום דאָ ווי אַ מענטש, נישט קיין שילוּיע

כאָטש אַלץ פֿאַרלוירן סײַ ווי סײַ

וועל איך פֿאַרלויבן אדני

און שרײַבן ווי לחיים הללויה

Read more: http://yiddish.forward.com/articles/200434/leonard-cohens-hallelujah-in-yiddish/#ixzz5DCVVG7pV

Haleluye

Read more: http://yiddish.forward.com/articles/200434/leonard-cohens-hallelujah-in-yiddish/#ixzz5DCVgGrrG

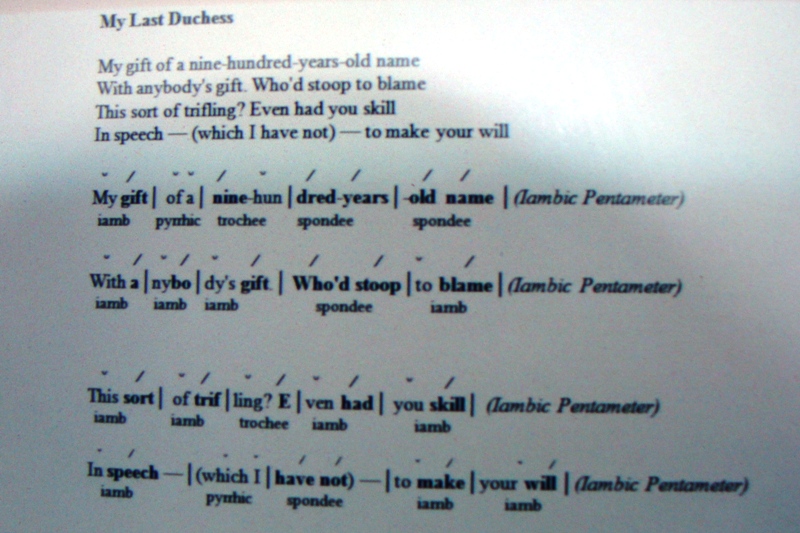

My last assclown

Since we have a thin-skinned assclown, a man-baby who rages in response to tweets, in the White House, I propose Robert Browning’s “My Last Duchess” for today’s National Poetry Month treat.

The chestnuts are blooming in the Place Cambronne. At this time of year, I stop there on my way home from work (on my way to work, I study vocabulary, and don’t notice them), and rejoice in the knowledge that they will survive even the zombie apocalypse. Of course, blooming chestnut trees means National Poetry Month; since we have a thin-skinned assclown–a man-baby who rages in response to tweets and threatens the press when he doesn’t like their reporting–a bigot who accuses judges of not being impartial on the basis of their parents’ national origin–an immoral villain who equates white supremacists and neo-Nazis with the people who stand up to them–with his fingers on the most powerful nuclear arsenal in the world, I propose a timely bit of Robert Browning. Follow this link if you’d like to hear a pretty good recording thereof. The poem is pretty disturbing in and of itself, and all the more so with Trump in the presidency. I gave commands; then all smiles stopped together. There she stands as if alive….Notice Neptune, though…thought a rarity, which Claus of Innsbruck cast in bronze for me! (Rough translation: I had her killed. Hey, look at this great thing that I have!)

The poem was published in 1842, and some of the language bears explication. I’ll give you the modern and/or non-poetic equivalents of some of the verbs:

- will’t: “will it” Will’t please you sit and look at her?

- durst: “dared” And seemed as they would ask me, if they durst, //

How such a glance came there;

- ’twas: “it was” Sir, ’twas not // Her husband’s presence only, called that spot // Of joy into the Duchess’ cheek;

- whate’er: “whatever” she liked whate’er // She looked on, and her looks went everywhere.

- whene’ever: “whenever” Oh, sir, she smiled, no doubt, // Whene’er I passed her;

…and the English notes explain some of the words that I used in writing this post.

My Last Duchess

Robert Browning

That’s my last Duchess painted on the wall,Looking as if she were alive. I callThat piece a wonder, now; Fra Pandolf’s handsWorked busily a day, and there she stands.Will’t please you sit and look at her? I said“Fra Pandolf” by design, for never readStrangers like you that pictured countenance,The depth and passion of its earnest glance,But to myself they turned (since none puts byThe curtain I have drawn for you, but I)And seemed as they would ask me, if they durst,How such a glance came there; so, not the firstAre you to turn and ask thus. Sir, ’twas notHer husband’s presence only, called that spotOf joy into the Duchess’ cheek; perhapsFra Pandolf chanced to say, “Her mantle lapsOver my lady’s wrist too much,” or “PaintMust never hope to reproduce the faintHalf-flush that dies along her throat.” Such stuffWas courtesy, she thought, and cause enoughFor calling up that spot of joy. She hadA heart—how shall I say?— too soon made glad,Too easily impressed; she liked whate’erShe looked on, and her looks went everywhere.Sir, ’twas all one! My favour at her breast,The dropping of the daylight in the West,The bough of cherries some officious foolBroke in the orchard for her, the white muleShe rode with round the terrace—all and eachWould draw from her alike the approving speech,Or blush, at least. She thanked men—good! but thankedSomehow—I know not how—as if she rankedMy gift of a nine-hundred-years-old nameWith anybody’s gift. Who’d stoop to blameThis sort of trifling? Even had you skillIn speech—which I have not—to make your willQuite clear to such an one, and say, “Just thisOr that in you disgusts me; here you miss,Or there exceed the mark”—and if she letHerself be lessoned so, nor plainly setHer wits to yours, forsooth, and made excuse—E’en then would be some stooping; and I chooseNever to stoop. Oh, sir, she smiled, no doubt,Whene’er I passed her; but who passed withoutMuch the same smile? This grew; I gave commands;Then all smiles stopped together. There she standsAs if alive. Will’t please you rise? We’ll meetThe company below, then. I repeat,The Count your master’s known munificenceIs ample warrant that no just pretenseOf mine for dowry will be disallowed;Though his fair daughter’s self, as I avowedAt starting, is my object. Nay, we’ll goTogether down, sir. Notice Neptune, though,Taming a sea-horse, thought a rarity,Which Claus of Innsbruck cast in bronze for me!

Want a French translation of this poem? See the Wikipédia page here.

English notes

assclown: “someone who, wrongly, thinks his actions are clever, funny, or worthwhile.” ““someone who seeks an audience’s enjoyment while being slow to understand how it views him.” A specific kind of asshole, defined as “A person counts as an asshole, when and only when, he systematically allows himself to enjoy special advantages in interpersonal relations out of an entrenched sense of entitlement that immunizes him against the complaints of other people.” Sources: John Kelly on the Strong Language blog, and Aaron James, in his book Assholes: a theory of Donald Trump.

Fra: “used as a title equivalent to brother preceding the name of an Italian monk or friar” (Merriam-Webster). My best guess is that it’s used here to suggest that the Duke things that the painter was overly familiar (brother) with his wife, and/or that his wife was overly familiar with the painter.

familiar: a word with at least two parts of speech (adjective, of course, but also noun). In the poem, it’s used with the meaning of informal, friendly; it can also mean something well-known (the familiar works of Shakespeare).