Sometimes having an accent is not a bad thing. For example: Sunday night I arrived in Nagasaki after almost 20 hours of travel. My typical experience upon arriving in Japan is that after many hours in planes, trains, and buses, I get maybe five minutes from the hotel, and then can’t find it. When I got in at 10:30 PM everything was closed, but I found a taxi. I got in, and had the following conversation with the driver. If something is in italics, it happened in Japanese:

Me: Good evening.

Driver: ‘Evening.

I hand him the map to the hotel that I have printed out and point at the hotel.

Driver: Which hotel is it?

Now I realize that (a) the map is really just a schematic, so it doesn’t show exactly where the hotel is, and (b) I absent-mindedly printed it off of the English-language version of the web site, so the taxi driver probably wouldn’t recognize the name of the hotel anyway. What to do?

English loanwords get used a lot in Japanese. I’ve found that I can sometimes make myself understood if I say an English word with a Japanese accent. The name of the place is the Luke Plaza Hotel, so I try this:

Me: Ruku Puraza Hoteru, please. (That is “Luke Plaza Hotel” pronounced with a Japanese accent.)

Driver: Ah, OK.

And we drive off! I was feeling pretty pleased with myself, because I hadn’t previously realized that I knew how to say “Which hotel is it?” in Japanese. Of course, what with me not actually speaking Japanese, it’s possible that he said “You REALLY smell like dog biscuits,” but we did get to the hotel, so I doubt it. Here is some vocabulary from the French Wikipedia page about Nagasaki, my home this week:

Avant que: `before.’ This expression is only simple deceptively, for two reasons: (1) it has to be followed by the subjunctive, and (2) it is involved with a construction that includes something called an expletive negative. Here is the example from the French Wikipedia article about Nagasaki: Sous la période Tokugawa, la persécution des chrétiens y fut particulièrement vive, avant que la ville ne soit ouverte après la restauration Meiji. “During the Tokugawa period, the persecution of Christians was particularly harsh, before the city was opened after the Meiji resoration.” We could do an entire blog post on this one sentence, but let’s just pick apart the avant que construction.

Syntactic expletives are words that are required by the syntax of the language, but don’t actually mean anything. An example of a syntactic expletive in English is the expletive or pleonastic pronoun in sentences like It’s raining or It’s important that you get there on time. Normally the English word it refers to something that has previously been mentioned, but the pronoun it in It’s raining doesn’t mean anything—you just have to have it in that construction in English.

In French, there are a number of morphosyntactic (i.e., related to specific words and sentence structures) phenomena that involve syntactic expletives. One of these is called the French expletive negative, an added negative particle where you wouldn’t expect it from the meaning of the sentence. The avant que construction is an example of this. If you do a morpheme-by-morpheme analysis of the example that we saw above, you have this:

| avant | que | la | ville | ne | soit | ouverte |

| Before | that | the | town | not | be | open |

The thing is, this means “before the town was opened”—it has a positive, not a negative, meaning. This is French negative expletion. It is simply a fun feature of the grammar of French. Let’s look at some Twitter examples:

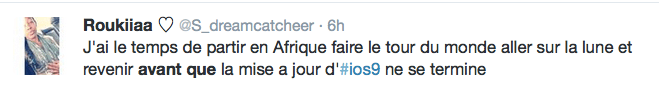

Now: it’s important to be aware that the expletive negative with avant que is a feature of proper written French, but it is often omitted in casual French. So, you might see something like this tweet:

…or this profile:

In fact, if you search for the avant que construction on Twitter, you will see far, far more tweets without the expletive negative than with it. However, you will notice that it is always followed by a verb in the subjunctive. Got any cute expletive negatives of your own? Why not post them in the comments?