Trigger warning: vulgar reference to reproductive anatomy. Oh, and National Poetry Month continues with Shakespeare’s Sonnet 73, That time of year thou mayst in me behold.

Thanksgiving Day is a purely American holiday. OK: it’s a harvest holiday, and practically everybody has a harvest holiday. But, it’s ours, and we love it. An American who is not with family and friends on Thanksgiving Day is a lonely American; les Amerloques will travel amazing distances and spend enormous amounts of money just to spend the last Thursday in November with their families, and then head back to wherever they normally are 48 hours later.

I studied literature and linguistics at a college in a little town in rural Virginia. Nobody was from there, so essentially the entire student body left to go home for the holiday. Thanksgiving Day is the last Thursday in November (I know I already mentioned that, but it seems weird enough to be worth repeating), and you have to leave a couple days before that to get home–but, when, exactly, can you leave? The college’s rule was this: classes ended at noon on Tuesday, and then you could do as you wished.

Classes ended at noon, and I had a class at 11. I was going nowhere, and I was a more-than-obsessive student, so you can bet your ass that I was there at 11. (You can bet your ass that explained in the English notes below.) Me–and the professor. And nobody else.

If I were that professor today, I would just take that student out for a cup of coffee and make them teach me about logarithms, I suppose. But, I’m a fat old bald guy who will be retired in the blink of an eye (English notes, don’t worry), and my professor was a young guy in need of tenure. He shrugged his shoulders–and taught me.

No, he didn’t lecture: I sat at a desk, he sat on the desk, and he taught me how to do a “close reading” of a poem. There must be a technical definition of close reading–my understanding of it is: look up every fucking word. Do that, and you are likely to be surprised at the connections that you see, the networks of words, the multiple champs lexicaux in the poem–maybe one was obvious to you, but there are probably more than that, and noticing them is part of the pleasure of the whole thing. (Taking pleasure in analyzing a poem to death might be another one of those reasons that I get divorced so often.)

The latest and greatest thing in literary studies is “distant reading.” It’s called that precisely to draw the clearest possible contrast with “close reading.” The idea behind distant reading is that you don’t actually read anything–rather, you use a computer to analyze entire literatures. As Franco Moretti, the godfather of this stuff, puts it: you can read one book, and then another, and then another, for the rest of your life–at the end, all that you will know is those books. If you want to understand literature, then you have to look at giant collections of it. People who do distant reading do what I do with biomedical texts, except they write their papers about things like this:

“The Emotions of London”, written by Ryan Heuser, Franco Moretti, and Erik Steiner, inaugurates a new field of work for the Literary Lab — that of literary and cultural geography. Working on a corpus of 5,000 novels, and covering the two centuries from 1700 to 1900, this pamphlet charts the uneven development of social spaces and fictional structures, bringing to light the long-term connection between emotion and class in narrative representations of London. Stanford Literary Lab

…rather than stuff like this, as I do:

Prior knowledge of the distributional characteristics of linguistic phenomena can be useful for a variety of language processing tasks. This paper describes the distribution of negation in two types of biomedical texts: scientific journal articles and progress notes. Two types of negation are examined: explicit negation at the syntactic level and affixal negation at the sub-word level. The data show that the distribution of negation is significantly different in the two document types, with explicit negation more frequent in the clinical documents than in the scientific publications and affixal negation more frequent in the journal articles at the type level and token levels.

I’ll leave it to you to decide which is the more interesting. Or, don’t choose–immerse yourself in both. Whatever–it’s all fun.

Today, we’ll go closer to the close reading end of the continuum with Shakespeare’s Sonnet 73–an appropriate one for a fat old bald guy such as myself, as it speaks of love at the end of life. (Obviously, it would be even more appropriate if I could ever get a second date–alas.) The target in our sights: the words Death’s second self, which have always puzzled me. (For context: I took three semesters of Shakespeare in college, and I mostly wrote my papers about linguistic aspects of the Bard, so things in his work don’t usually perplex me for decades, like Death’ second self has.) That second self is pretty goddamn opaque to a native speaker of English–today. It is an old term that has a meaning of its own:

second self: one who associates so closely with a person as to assume that person’s mode of behavior, personality, beliefs, etc. (Dictionary.com)

Now, you have to realize: linguists approach dictionaries with more than a little bit of suspicion. Make it an on-line dictionary of unclear provenance, and my antennae really go up: is this a justifiable definition, or did whoever wrote it base it entirely on their interpretation of its appearance in Shakespeare’s sonnet?

I can’t know what was in the definition writer’s head–hell, I can’t even tell you what’s in any of my many ex-wives’ heads (see previous mentions on this blog of how often I get divorced). Honestly, most of the time I’m not even sure what’s in my head. But, I can look at some data–that’s what linguists do, right? (That’s a bit of sarcasm, but I’m wandering way too far off the track of National Poetry Month already.) Off I go to the Sketch Engine web site, purveyor of fine linguistic corpora and the tools for searching them, where I find the English Historical Books Collection, containing 826,000,000 words of text from English books published between 1473 and 1820. A search for second self shows me that the phrase occurs at a rate of 0.04 times per million words, and gives me examples like this:

- …one correspondent to him, suitable both to his nature and necessity, one altogether like to him in shape and constitution, disposition and affection, a second self …

- THERE is the Relation of Trustees to those that trust them: for he who trusteth another doth thereby create a very near and intimate Relation to him; so far forth as he trusteth him, he putteth his case into his hands, and depositeth his Interest in his Disposal, and thereby createth him his Proxy, or his second self.

- God is the most Pure, Simple, Uncompounded Being; and if God, who has no parts, and cannot be divided into any, begets a Son, he must Communicate his Whole, Undivided Nature to him: For to beget a Son, is to Communicate his own Nature to him; and if he have no parts, he cannot Communicate a part, but must Communicate the Whole; that is, he must Communicate his whole self, and be a second self in his Son.

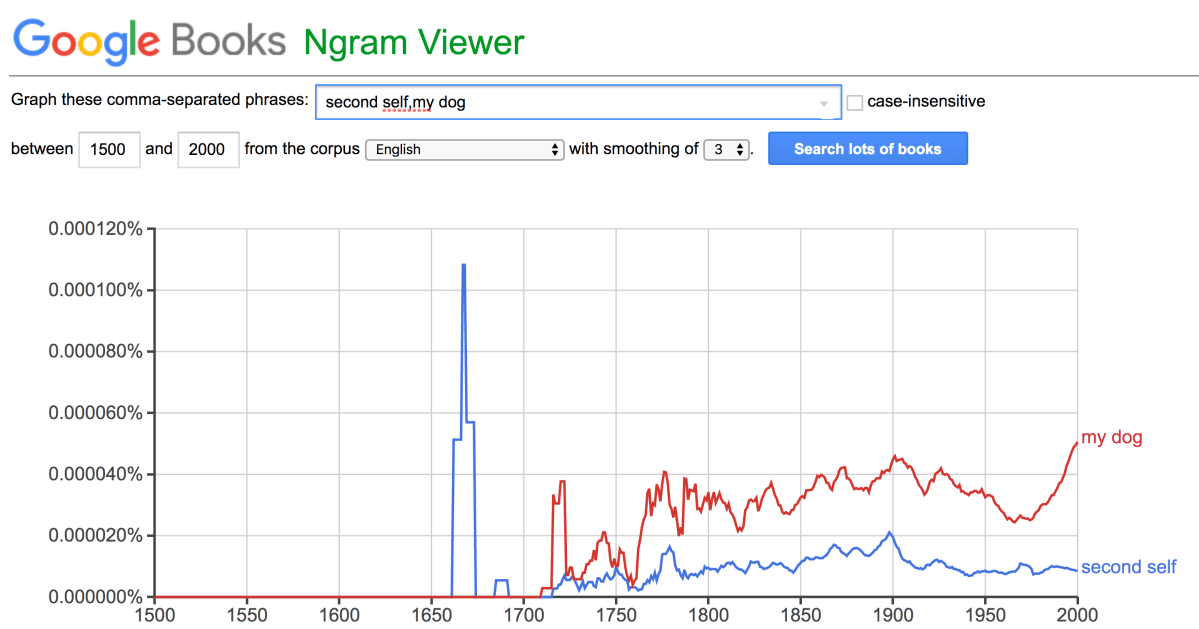

So: I don’t know how the lexicographer came up with their definition, but it looks pretty consistent with the data that I found. How common was it, actually? I did a search for it in Google Books between the years 1500 and 2000. You’ll see a graph of the output at the end of this post. Why did I also search for my dog? Because numbers in isolation mean nothing–in order to know whether a number is large or small, you have to compare it to something else. (The best movie line ever: 5 inches is a lot of snow, and it’s a TREMENDOUS amount of rain, but it’s not very much dick.) So, I picked a phrase that isn’t necessarily very frequent (relatively speaking), but isn’t exactly weird, either.

…And with that fabulous line from the incredible film L.I.E., I’ll leave you with Shakespeare’s Sonnet 73. Scroll down past the graph that follows it for the English notes, and I hope that your second self (should you have one) is every bit as nice as you are.

Sonnet 73

William Shakespeare

That time of year thou mayst in me behold

When yellow leaves, or none, or few, do hang

Upon those boughs which shake against the cold,

Bare ruined choirs, where late the sweet birds sang.

In me thou see’st the twilight of such day

As after sunset fadeth in the west;

Which by and by black night doth take away,

Death’s second self, that seals up all in rest.

In me thou see’st the glowing of such fire,

That on the ashes of his youth doth lie,

As the deathbed whereon it must expire,

Consumed with that which it was nourished by.

This thou perceiv’st, which makes thy love more strong,

To love that well which thou must leave ere long.

https://books.google.com/ngrams/interactive_chart?content=second+self%2Cmy+dog&year_start=1500&year_end=2000&corpus=15&smoothing=3&share=&direct_url=t1%3B%2Csecond%20self%3B%2Cc0%3B.t1%3B%2Cmy%20dog%3B%2Cc0

That spike centered around 1670 or so? Could be real, but you would want to verify it–things like that in any kind of graph tend to reflect either some event that it should be very easy to track down, or a problem with the data itself.

English notes

you can bet your ass that… “You can believe that it is absolutely true that…” This is quite vulgar–don’t say it in front of my grandmother. Some examples:

- If someone is trying to kill me and/or my loved ones, you can bet your ass that I’ll take him out first.

- #1 Rule … If it sounds like a good deal and is widely advertised, you can bet your ass that you are not the first person to call, and if its such a marvelous deal how come its still for sale?

- Oh and you can bet your ass that neither one of them will be in a good mood at 6:00 when I wake them.

- Sadly, Ted, if you examine his statements, then see that he specializes in benefits & employment law, you can bet your ass that his clients are vicious capitalist pigs, who love his union- & employee-busting ways.

(Examples from the enTenTen13 corpus–19.7 billion words of written English, searched via the Sketch Engine web site.) How I used it in the post: I was going nowhere, and I was a more-than-obsessive student, so you can bet your ass that I was there at 11.

you bet your ass: this is basically a very emphatic (and vulgar–don’t say it in front of my grandmother) way of saying “yes.”

- Am I using a bunch of recycled selfies? You bet your ass I am (Twitter)

- Not even gonna lie, I ordered chinese food yesterday night and while I was eating I found a pinkie nail sized piece of plastic in it. Was I grossed out? Yeah. Did I keep eating? YOU BET YOUR ASS (Twitter)

- Me, depressed? You bet your ass (Twitter)

- Just got offered a trip to Florida so I can lay by the pool&drink at our family friend’s new house and be bait to get his son and college buddies there to help move furniture… You bet your ass I said yes (Twitter)

in the blink of an eye: very fast, very quickly, immediately.

- One wrong turn in an Ikea and you can go from bathrooms to bedroom furniture in the blink of an eye, losing the other members of your party just as quickly.

- Now, with the advent of social media, you can turn to a quarter million people and get their opinion in the blink of an eye–as long as you have sophisticated tools like NetBase’s to automatically analyze all that chatter so quickly.

- But if they didn’t go along with her every whim, or worse, wanted to stop the relationship, she would go from singing their praises to trash-talking everything about them in the blink of an eye.

How I used it in the post: But, I’m a fat old bald guy who will be retired in the blink of an eye, and my professor was a young guy in need of tenure.

Suddenly Bruant’s poem made sense. Faire sentinelle: to stand guard, but also to have an erection. La chapelle: chapel, but also vagina. Other plays on words are more obvious, at least to a veteran (which I am, but Trump isn’t, having been excused from Vietnam due to a sore foot, although apparently said foot did not deter him from being

Suddenly Bruant’s poem made sense. Faire sentinelle: to stand guard, but also to have an erection. La chapelle: chapel, but also vagina. Other plays on words are more obvious, at least to a veteran (which I am, but Trump isn’t, having been excused from Vietnam due to a sore foot, although apparently said foot did not deter him from being