I’m going to die in 2028. I calculated this by starting with my year of birth, adding the median of my father’s and paternal grandfather’s ages at the time of their first heart attacks, subtracting a bit for my smoking as a teenaged problem child, adding a bit for my maternal grandfather’s long life despite his smoking (a friend of my mother’s once described my grandfather’s apartment to me as “nothing but books and cigarette smoke”), subtracting a bit for the deleterious effects of years of high cortisol production due to years of incredible stress (I have my own problem child), and adding a bit for the salutary effects of ten years of intensive study of the incredibly physically demanding sport of judo. 2028 works out great for me–I can retire and spend a couple years sitting around reading, and then croak right about the time that my paltry retirement savings run out.

The verb mourir, “to die,” turns out to be quite irregular in French, and since we’ve been working our way through irregular verbs, il serait séant q’on l’étudiât. (That’s a little French morphosyntax joke. A double joke, actually, since séant means both the very literary “fitting, seemly” and “backside, behind”–roughly fesses, if you’re French.) As far as I can tell, some verbs have similar conjugations, but no other French verb is conjugated quite the same as mourir. Let’s tour the various and sundry tenses and aspects.

Present indicative

Mourir has a vowel change in the present tense that is almost all its own–the only similar verb that I can think of is émouvoir. But, émouvoir is quite different even in this tense, as the third person plural form (ils/elles) has the root-final consonant of the other plurals, rather than the (lack of a) root-final consonant in the singulars, which is how mourir works.

| je meurs | nous mourons |

| tu meurs | vous |

| on meurt | ils/elles mourez |

Imperfect indicative

As far as I know, even irregular verbs are all regular in the imparfait, or imperfect indicative.

| je mourais | nous mourions |

| tu mourais | vous mouriez |

| on mourait | ils/elles mouraient |

Passé simple (past historic)

Mourir is irregular in its own special way in the passé simple. It takes the same endings as a set of irregular verbs that have past participles that end with u, but its past participle does not end with u. (It’s mort(e).) (See Laura Lawless’s page on the passé simple on About.com for the full set.)

| je mourus | nous mourûmes |

| tu mourus | vous mourûtes |

| on mourut | ils/elles moururent |

Passé composé (compound past)

Of course, mourir has to be different and make the compound past with être, rather than as most verbs do, with avoir:

| je suis mort | nous sommes morts |

| t’es mort | vous êtes morts |

| on est mort | ils sont morts |

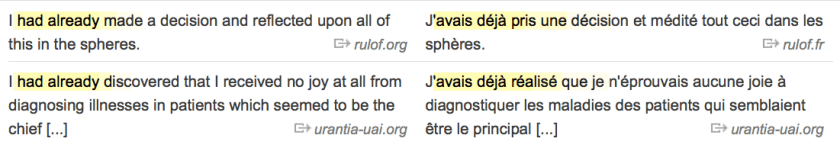

Futur simple (future indicative)

This is one of those double-rr-in-the-future-tense verbs that we ran into in a recent post on irregular future-tense verbs.

| je mourrai | nous mourrons |

| tu mourras | vous mourrez |

| on mourra | ils/elles mourront |

Present subjunctive

Mourir has the same unusual root vowel change in the present subjunctive as it has in the present indicative.

| je meure | nous mourions |

| tu meures | vous mouriez |

| on meure | ils/elles meurent |

Imparfait du subjonctif (imperfect subjunctive)

Mourir is irregular in the imperfect subjunctive in the same way that it’s irregular in the passé simple, which is to say that it has a u in the stem

| je mourusse | nous mourussions |

| tu mourusses | vous mourussiez |

| on mourût | ils/elles mourussent |

Participles

There are only three French verbs that have irregular present participles, and amazingly, mourir isn’t one of them. The past participle is irregular, though–it doesn’t end with the i that a regular -ir verb would end with, but rather with a t(e) (depending on whether we’re talking about something grammatically male or grammatically female):

| present: mourant | paste: mort |

Imperatives

Weird stem vowel change, once again:

| mourons! | |

| meurs! | mourez! |

I believe it was the famous French philosopher and essayist Montaigne who said that “to learn to philosophize is to learn how to die.” (An interesting contrast with my peeps at the café philo who felt that the point of philosophy is to learn how to live.) Any way you slice it, if you’re going to die (and at some point you are), now you know how to talk about it in French.