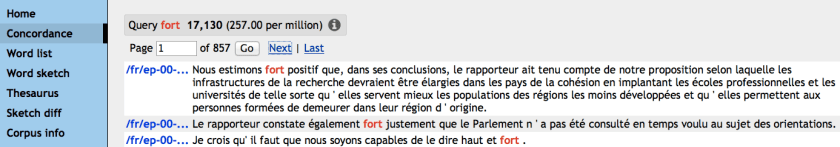

Like I always say: it’s the little things that get you. One of the things that I love about France is that people feel totally free to correct each other’s language, and they certainly feel free to correct mine. (Truly, I love this–it’s such a help in trying to learn the language.) I gave a talk in French the other day. Descriptivism versus prescriptivism, duality of patterning, how even very small choices in building computer programs for processing human languages can imply stances on very contentious issues in linguistics–all that kind of good stuff. I had memorized the relevant French vocabulary–la référentialité (referentiality), l’épistémologie (epistemology), inné (innate). I was about as ready as I could be.

Not ready enough, it turns out. One of the folks in the audience came up to me afterwards to explain a not-very-subtle word choice error that I had blown. My mistake: I said “phrase” wrong. I was talking about groups of words smaller than a sentence, and used the French word la phrase. Not okay! La phrase means “sentence.” If you want to talk about phrases, you need another word. What that word is–that’s not so clear.

Why would one want to talk about phrases, anyway? One of Chomsky’s contributions to linguistics that didn’t suck was demonstrating that syntax isn’t about relationships between words–rather, it’s about relationships between groups of words. Matt Willsey gives a nice example that illustrates how this works. In English, one could say:

- If x, then y.

- Either x, or y.

You can embed these:

- If (either x or y), then (either x or y).

You can embed things in those, too:

- If either (a or b or c or d), then either (e and f or g and h) or (i and j but k and l).

The point: you get nowhere trying to explain this kind of hierarchical structure by means of the behavior of words. On the other hand, you can get very far by discussing this kind of hierarchical structure in terms of groups of words.

In linguistics, we tend to refer to these groups of words as phrases. English has noun phrases, verb phrases, and prepositional phrases–maybe more, but at least these. (At some level, a sentence is just another kind of phrase, but we do tend to maintain some notion of “sentence.”)

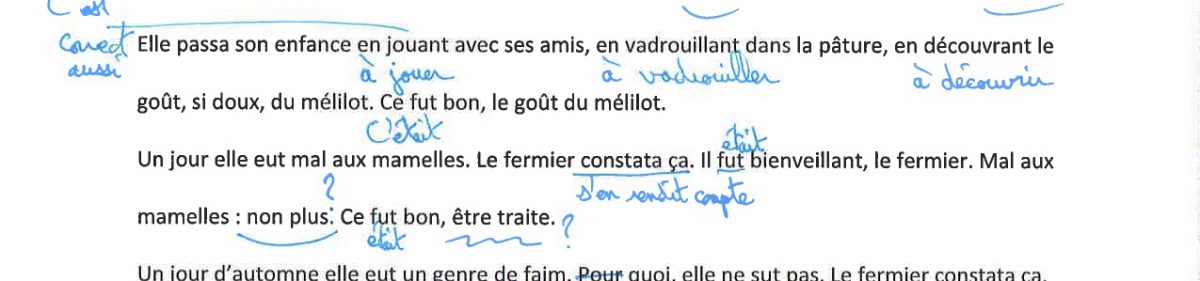

Phrases are typically thought of as having something called a head. From a syntactic point of view, you could think of the head of the phrase as the thing that determines whether the phrase behaves as a noun, a verb, or whatever. In the following phrases, I’ve bolded the head:

- those bananas from the corner store

- this banana that I got from my cousins

To see why I say that the head determines how the phrase behaves, consider these sentences:

- Those bananas from the corner store are almost rotten.

- This banana that I got from my neighbors is just about ready for the trash can.

Prior to Chomsky, the most fully elaborated theory of how syntax works is that it was about connections between sequences of words. What you can’t explain with that kind of model is how you can have sequences like the corner store are or my neighbors is. To account for sequences like that, you have to have some notion of structure that can let you represent the fact that it’s the head of a group of words that controls whether the verb is singular (is) or plural (are).

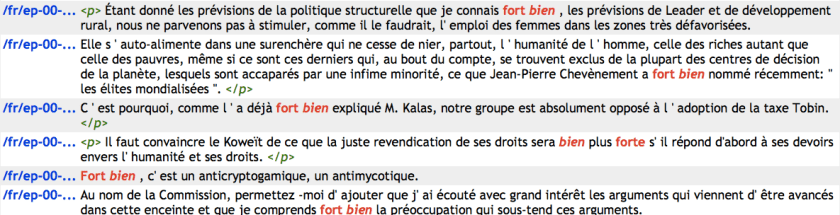

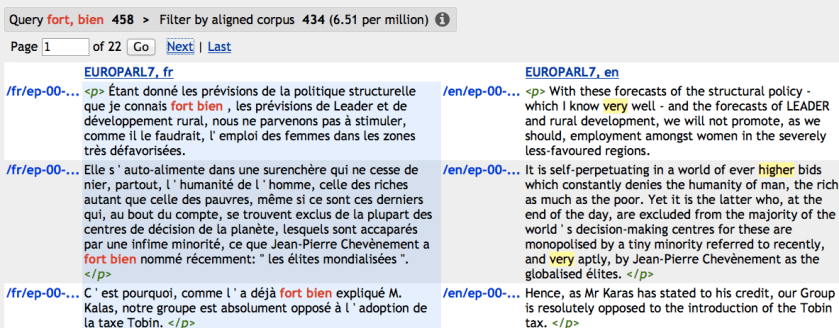

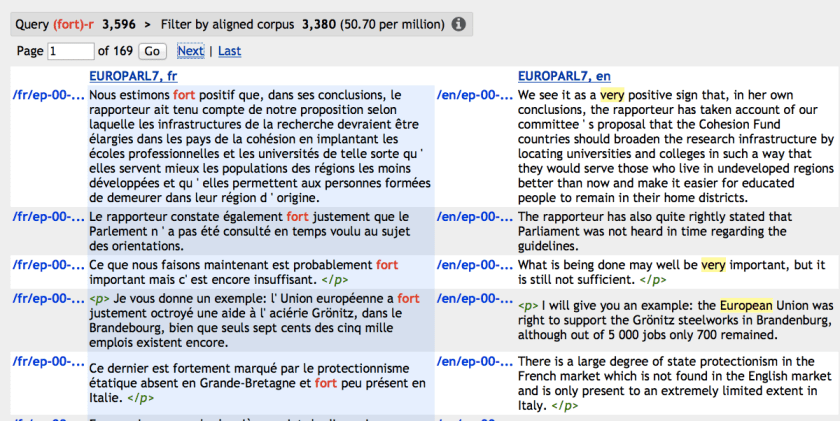

So, how do you talk about “phrases” in French? That’s where my problem came up, and how I ended up sounding stupid. One of my ways of trying to find acceptable technical terminology is to look things up on Wikipedia in English, and then follow the link to the corresponding French-language page. No love: there’s an English-language page for noun phrase, but no corresponding French page. Around the lab, some of the students call them phrases–phrase nominale, phrase verbale, etc. The issue: la phrase is typically used to refer to a sentence. When I gave my talk, I used the word la phrase to mean “phrase,” as some folks do around the lab. It didn’t go over well.

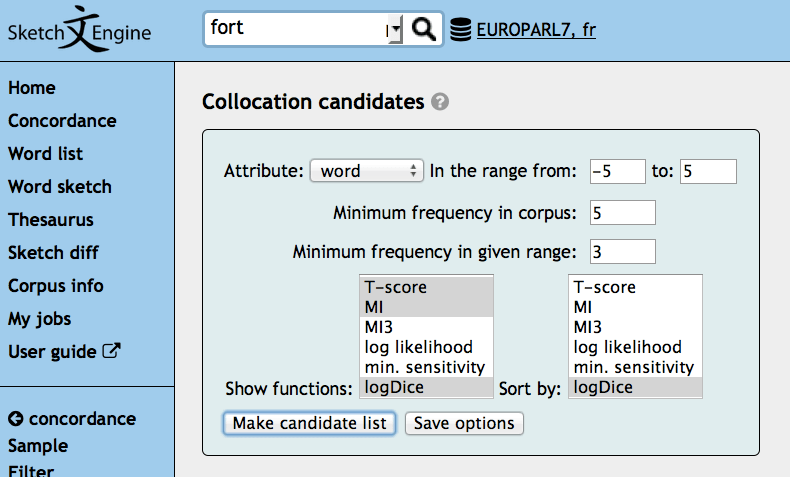

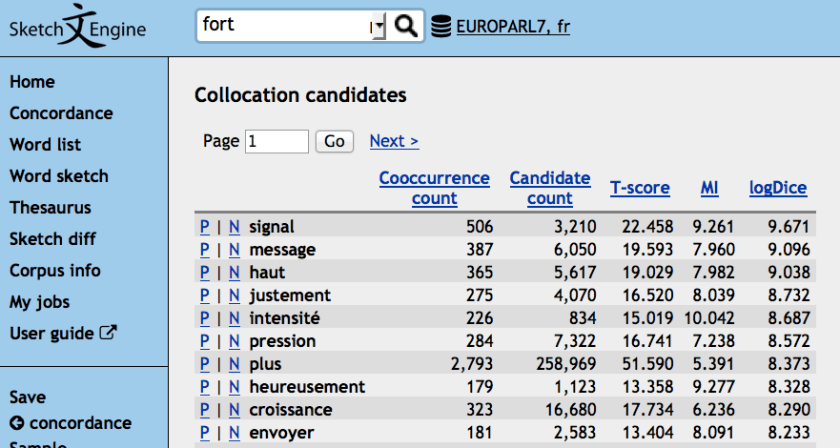

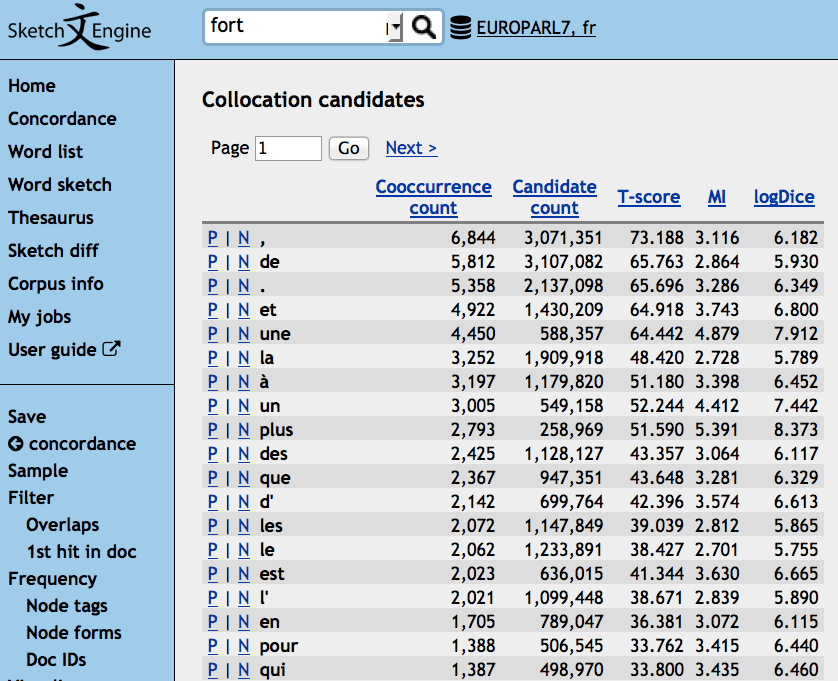

So, what do you call a phrase in French? Here are some options that I’ve found. The one that has the most support in terms of the number of places where I found it used is one that I have never actually heard!

- le groupe nominal/les groupes nominaux (Linguee.fr)

- la locution nominale (Linguee.fr)

- le syntagme nominal (Linguee.fr; Denis Roycourt’s Noam Chomsky: une théorie générative du langage, in Le langage: nature, histoire et usage, edited by Jean-François Dortier; Maurice Pergnier’s Le mot)

I even came across this, in Maurice Pergnier’s Le mot:

C’est également avec ce sens qu’on rencontre le terme [syntagme] dans les traductions françaises des ouvrages de Chomsky, pour traduire le mot anglais “phrase” (Noun-Phrase; Verb-Phrase = syntagme nominal; syntagme verbal).

Perpignon goes on to add: Il faut noter cependant que, pour cette…école, le syntagme (angl. “phrase”) ne se définit pas seulement comme ensemble d’unités minimales, il se définit surtout comme partie de phrase, puisqu’il est dégagé par découpage de la phrase (“sentence”) selon la structure arborescente.

So, we have a very explicit contrast between le syntagme (English “phrase”) and la phrase (English “sentence”).

Now that we know how to talk about phrases, in French and otherwise: getting a computer to find the heads of phrases can be a lot harder than it is for humans to do it. There’s a very cool web site that lets people play a game that’s designed to create data to be used to help computers learn for themselves how to find the heads of phrases in French. It’s called Zombi Lingo: zombie, ’cause you have to find heads, and zombies like to eat brains. (Clearly this is a pre-Walking-Dead conception of what it means to be a zombie.) Check it out at this link–it’s quite fun.

So, yeah–I gave a talk in which I explained duality of patterning, but screwed up the word for “phrase.” Oh, well–as Jigoro Kano, the founder of judo, would have put it: I got valuable insight into what I need to work on.

Incidentally, here are some details on some of the 85 gun deaths in the United States in the past 72 hours:

- 3 people in one incident, Marion County, Oregon (source here)

- 1 church deacon in Shelby County, Tennessee (source here)

- 1 person in Houston, Texas (source here)

- 1 person in San Antonio, Texas (source here)

I really don’t have the stomach to go through all 85 of them–sigh… 72 hours, 85 deaths…

When my kid was about four years old, he went through a period where he switched the orders of certain kinds of words. It wasn’t random–this happened only with a particular kind of word formed by putting two nouns together. For example, he would say:

When my kid was about four years old, he went through a period where he switched the orders of certain kinds of words. It wasn’t random–this happened only with a particular kind of word formed by putting two nouns together. For example, he would say: