If you’re a native speaker of American English, you probably giggled childishly at the title of this post–I will admit that I did while watching the video that inspired it. I’ll explain why in the English notes below.

It’s no secret that food is a huge part of French culture, and it’s no secret that cheese is a huge part of French food. You will often read that “the cheese course”–the traditional end of a French meal–is disappearing from French tables, but I can tell you this: I have never had a dinner in a French home that didn’t have one. Rather than being the absolute end of the meal, it might be followed by the optional French fruit course, or it might be followed by a sweet, American-style dessert–and it’s certainly the case that I have no reason whatsoever to think that the small number of meals that I’ve had in French homes were in any way typical. But, for my sample, it remains the case that the cheese course lives.

I go back and forth between France and the US pretty frequently–three times in the past month (excessive even for me). The hardest thing about adjusting? Table manners. No sooner do I get used to keeping both hands on the table while I eat (obligatory in France–to do otherwise would be low class) than I find myself back in the US, where I must have one and only one hand on the table while I eat (to do otherwise would be low class). I’m well aware that there are a bazillion other aspects to good table manners in France–and well aware that I have no clue what they are. So, I was happy to see that the always-adorable Géraldine of the Comme une française YouTube series has just put out a video on the subject.

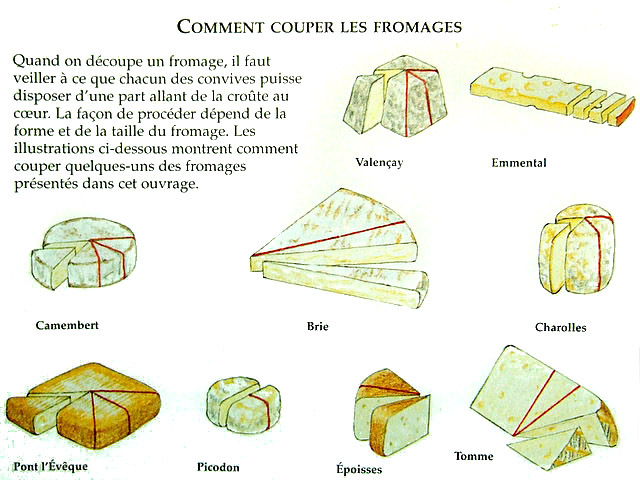

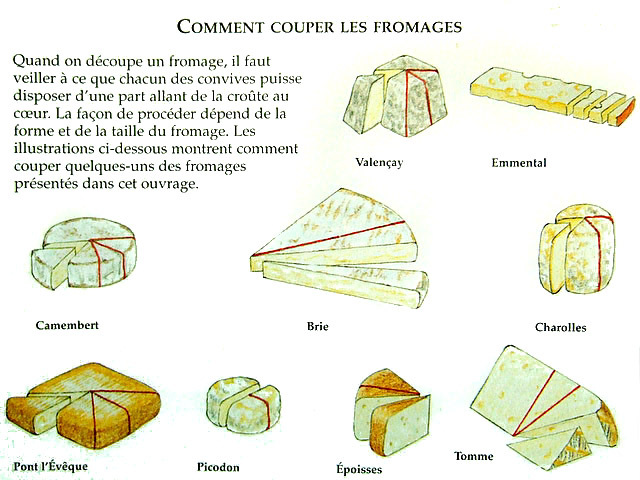

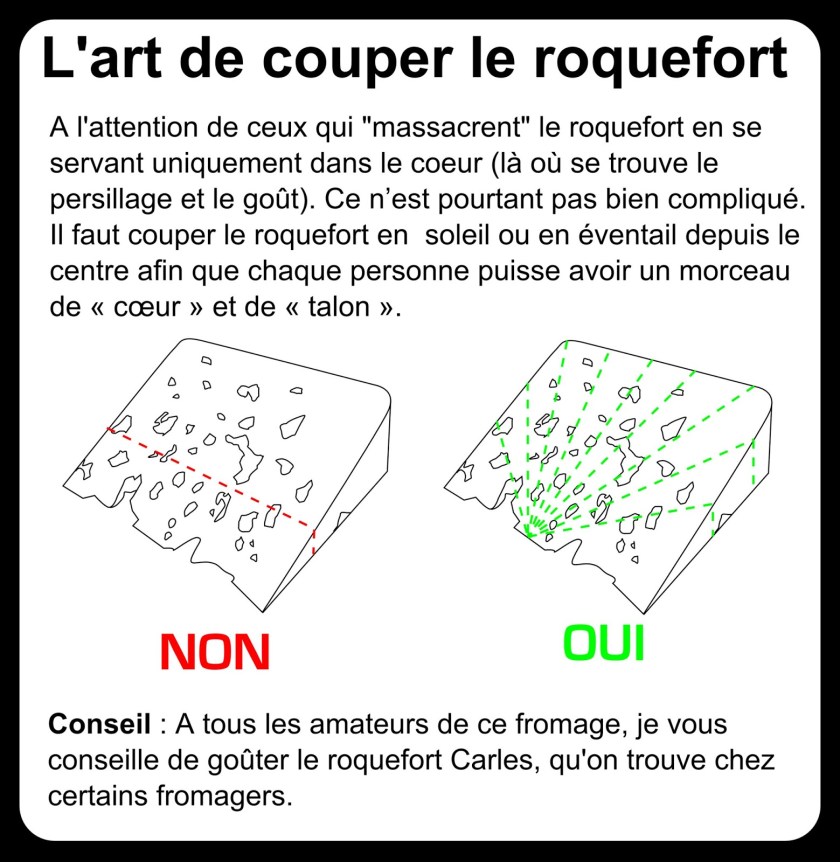

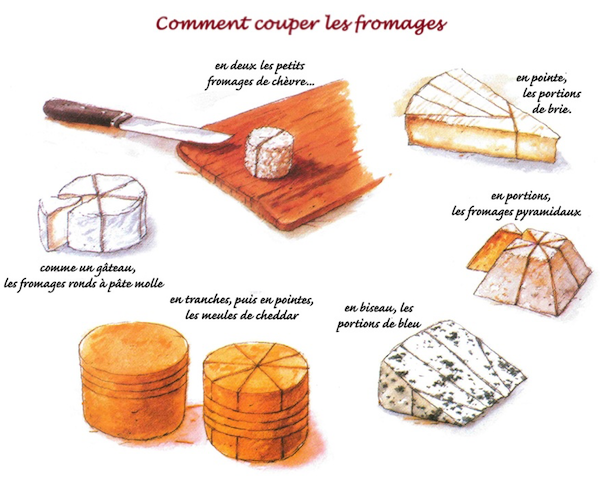

So, how does one cut a cheese? It depends on the shape and size. The graphic below makes the main point, as far as I know:

…il faut veiller à ce que chacun des convives puisse disposer d’une part allant de la croûte au coeur.

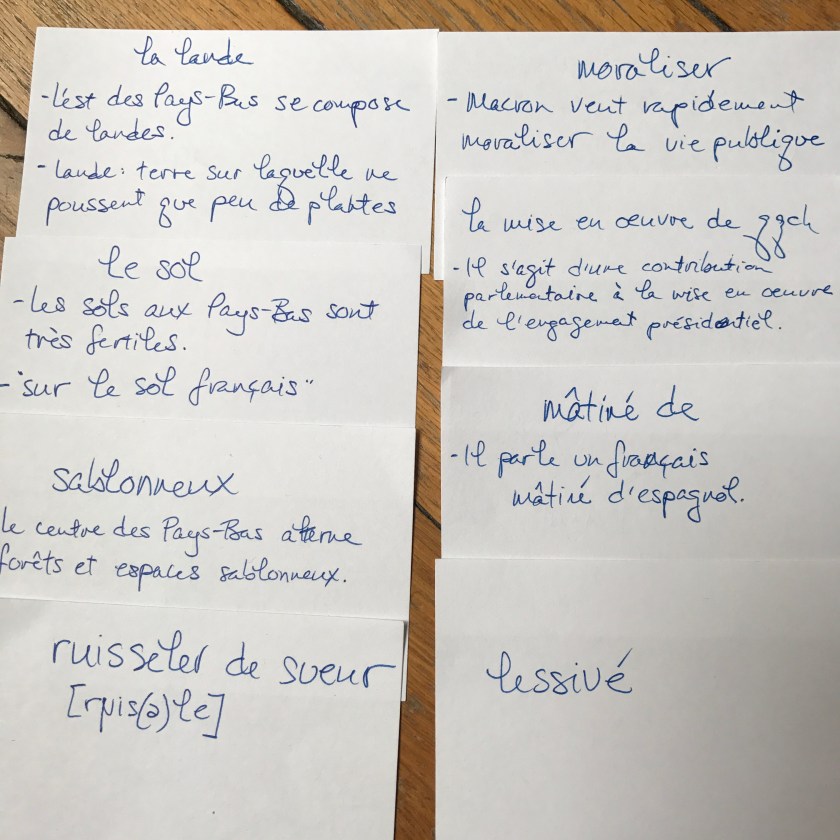

Linguistic points of interest:

- le convive : this is a guest, but from what I understand, it is specifically a guest who has been invited for a meal. So, this wouldn’t apply to, say, someone coming to spend a week with you.

- veiller à ce que + subjonctif : I think this means something like to make sure that.

- disposer de quelque chose : to have something at your disposal, to have something available

- la croûte : the rind of the cheese. You probably already knew this one, but I try not to miss a chance to write a circumflex accent.

- le coeur : this is the center of the cheese.

There are actually a number of different kinds of cheese knives. I think that they’re destined for cheeses of different degrees of softness/firmness, but I haven’t yet found a good source for information about these. Anyone have suggestions?

So: the thing to do, when cutting a cheese, is almost always to make sure that you do not, almost ever, cut off the center. The rationale behind this is that the cheese ages at different rates on a gradient between the center and the outside, and you want to make sure that everyone gets the chance to appreciate the subtle changes in taste. (I’ll admit right up front: over the past three years, I have eaten an enormous amount of cheese, and I can’t tell the difference.) Although the graphic below doesn’t show it, there are actually some cheeses where it’s OK to slice from the center; I think they’re the hard ones, but hard in this case means hard, not just solid. (Note the tomme in the lower-right corner–Americans would typically consider a tomme to be a hard cheese, I would guess, but we’re talking about things like parmesan here.)

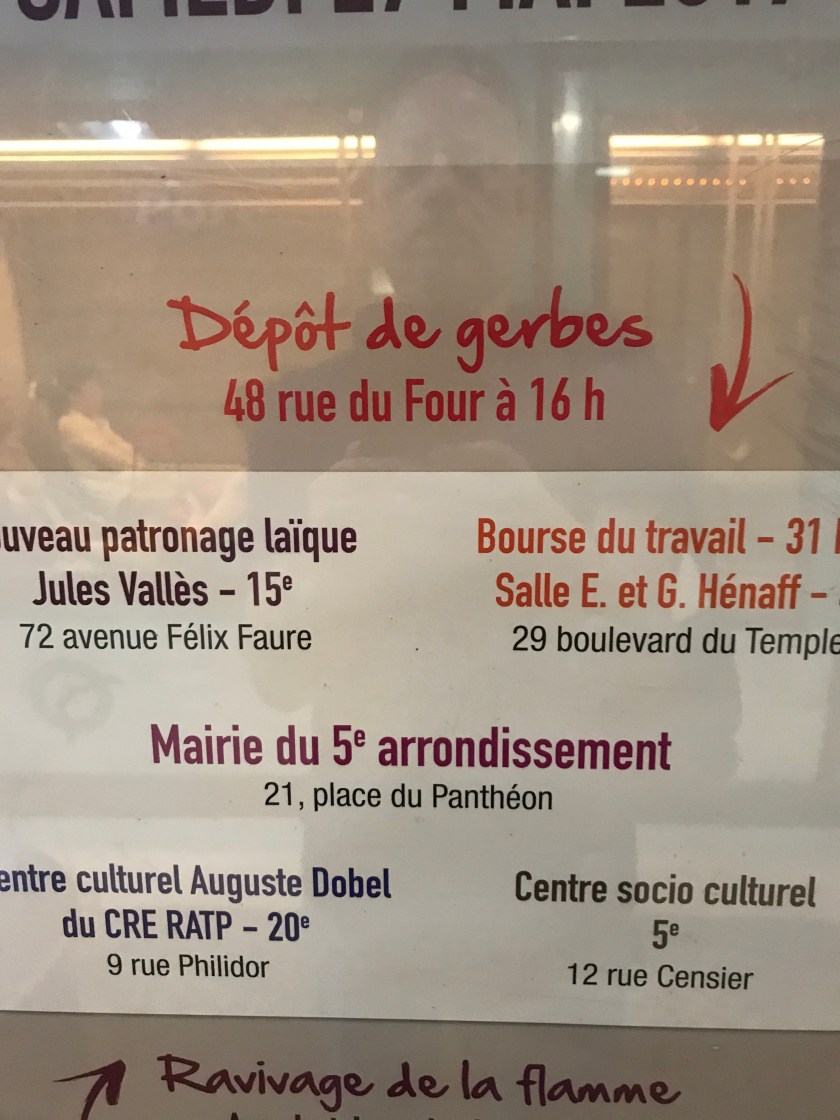

This nice graphic comes from a page that waxes quite eloquent about why it just doesn’t make sense to cut a roquefort any other way than this. A nice additional point of vocabulary: le talon (heel) for the end of the slice that’s away from the center.

Now, here’s someone who’s OK with you cutting the point off of a brie. But, notice: You’re not just cutting the point off–you’re cutting it at an angle, such that the other slices, mostly fan-shaped, will get well towards the center. Why would this be OK? Probably because bries in France are big. What is sold as a brie in the United States is actually about the size of a camembert in France. In contrast, bries are considerably larger here. While a camembert is about the size for one meal if there are a few people eating, a brie is a big family-sized thing. You would get quite a few meals out of one, or even out of a good-sized slice of one, if your family isn’t huge.

Here’s someone else who’s OK with cutting a brie in this way:

So, what’s so funny about Géraldine’s delightful video? At one point, she makes reference to cutting the cheese. In English (American, at any rate), to cut the cheese is slang for to fart. To cut a cheese doesn’t mean that at all–it means that there’s a cheese, and you’re going to cut it. To cut the cheese: to fart. Clear?

So, yes–it’s childish, but native speakers probably giggled at the title of this post. Here are some more examples, mostly referring to Trump.

Let’s make some nachos! You cut the cheese! *farts and laughs at his own bad joke*

— Jon’s Dad (@JonDadBot) May 29, 2017

@AynRandPaulRyan @FLOURNOYFarrell @realDonaldTrump @marchfeed Brandishing a look of holy sh*t, who cut the cheese,Fonzi.

— william a herrick (@herrick_a) May 29, 2017

“Who cut the cheese?”#G7Summit #Trump #Macron pic.twitter.com/9Zkepi82fo

— [401] (@seeker401) May 29, 2017

“Who cut the cheese?”#G7Summit #Trump #Macron pic.twitter.com/9Zkepi82fo

— [401] (@seeker401) May 29, 2017

The guy on the right has cut the cheese and the others are bailing #Bullseye pic.twitter.com/v2VYU0fND8

— Bully’s Speedboat (@BullysSpeedboat) May 21, 2017