A few years ago, I broke a finger in a judo class. It was nothing spectacular–I got my finger wrapped up in a guy’s collar, somebody moved the wrong way, and I felt it snap. I scooted over to one of the aged teachers with half of my finger pointing out at a weird angle, he grabbed it and did something and it stopped hurting, and I went home and taped it up.

Over the course of the following weeks, I learned to type with one non-functional finger, and all was fine. I spend the vast majority of my day typing, and I just kept doing the same thing for years–no problem.

Then I started hanging out in France, and writing lots of emails in French. I never learnt to switch to a French keyboard, so I’ve been doing digital (in the sense of “with my fingers”) gymnastics to write the many accented characters, and that’s been fine, too.

However, the other night I was awake working into the wee hours of the morning. 2 AM came along, and I was tired and had an aching headache, along with the arthritis that I always have in that broken finger. All of a sudden those digital gymnastics weren’t so OK. In my next email, I included a little note: I’m going to start writing an s instead of an accent. (If it’s in italics, it happened in French.) So, même became mesme, écrire became escire, and so on.

This elicited no comment whatsoever–the email correspondence went on just as if I was using accents normally. The reason that this could work without a hitch: in using an s instead of an accent, I was just going back to an older French spelling.

People often ask why French spelling is so bizarre. They ask the same thing about English. The cool thing is, they’re both bizarre in the same way. This is because both spelling systems primarily try to reflect not the pronunciation of a word, but rather its meaning and/or history. So, in English, we have the spellings electric, electricity, and electrician–three different pronunciations of that second c, which reflects how we say the word pretty poorly, but reflects very nicely the relationships in meaning between the three words. We write knife and knight, which reflect the pronunciations of those words poorly, but reflect very nicely the history of those words, which originally did start with a k sound.

French spelling tends to work the same way. Tête has an accent over the first ê to reflect the fact that it was originally teste. Écrire with its accent over the first é reflects the fact that it was originally escrire.

The title of this post implies that this is an Old French pronunciation and spelling, but I could just as well have said Middle French. This is because there’s not a lot of cross-dialectal consistency in when these s‘s disappeared, and there’s also not a lot of consistency in when various and sundry authors started reflecting that change in pronunciation by replacing the disappeared s’s with accents.

You may be wondering: if s’s disappeared, why does French still have them? How can we have saint, sacré, and savate? In this case, it has to do with the fact that the s’s went away only before other consonants. Saint: no problem, because the s is before a vowel. Teste becomes tête because the s preceded a consonant. So: how can we have écrire from the original escrire, but still have escroc? How can we have tête from teste, but still have test? The answer is typically related to when the words entered the language. Teste is an original French word, descended from Latin. Test was borrowed from English late in the 17th century, long after the loss of s in front of a consonant (probably around the 11th century, but see above about the inconsistency in the timing), and it didn’t undergo that change.

You can see similar patterns in English. English words that start with the sh sound typically were originally pronounced with an sk–shirt, ship, shape, etcetera. Often, though, we also have a corresponding word that comes from the same root historically, but is pronounced with an sk sound. Shirt and skirt come from the same root; ship and skiff; and a number of others. How can we have both the sh that developed from sk, and also the sk sequences? Because the sh words were original to the various and sundry Anglo-Saxon varieties. The words with sk were borrowed from various and sundry Old Norse words from the same roots, Old Norse being the language spoken by the Vikings who beat the shit out of England (and much of the rest of Europe, including a lot of northern France) in the Middle Ages. This was after the sk t0 sh change had happened in Old English, and we kept the sk sounds in those new words.

Now, the whole accents-over-vowels thing in French is all more complicated than this. Here are some facts that I’ve left out of the discussion:

- other consonants disappeared and also get reflected with an accent

- there was a vowel lengthening that I haven’t talked about that’s also reflected in the current uses of accents

- some accents are probably there purely to indicate differences in meaning, without necessarily reflecting former differences in sound

- the evolution of the spelling system is still ongoing, and the use of accents is one of the things that will change somewhat when the next spelling reform becomes official at the beginning of the 2016 academic year

- there are other things that contribute to the bizarreness of both French and English spelling, particularly in the case of vowels in English

If you want more of the technical details and can read French, I would suggest starting with this Wikipedia page on French spelling, and then following the link to this page on the accent circonflex in French.

My arthritic formerly-broken finger still hurts most days, but I’m not as cranky as I was the other night, and I’ve gone back to typing accents again. I find it interesting that when the spelling reform showed up in the news this past winter, many of the most vociferous complaints came from native speakers of English, rather than from French people–the general attitude was something along the lines of “I spent years learning those fucking accents–you can’t take them away from me now!” For my part, I find them quite charming–half of the fun of writing French is those accents, and my favorite French words tend to be ones where every possible vowel has an accent. So: yes, French and English spelling are both quite bizarre, but there’s a method to the madness, and you can make a good case that they improve reading comprehension. So, try to accept them both in good humor–there are plenty of worse things to complain about in the world.

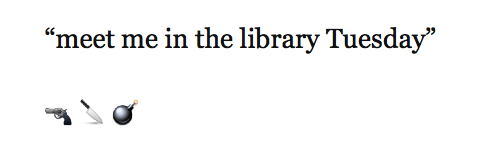

Case in point: Republican politicians are mostly up in arms about two things right now. One of them is regulating which bathrooms transgender people should use. The other is ensuring that Americans can easily get access to firearms. The most frequently-cited justification for controlling which bathrooms transgender people use is the possibility of a male-t0-female transgender person sexually molesting a female. I don’t know what the most frequently-cited justification for ensuring that Americans can easily get access to firearms is. What I do find interesting in this context is the following sets of numbers. The number of times that a male-to-female transgender person has sexually molested a female in a bathroom is 0. That’s zero, if you have trouble reading numbers on a computer screen. The number of firearm deaths in the United States in the past 72 hours is 69. Here are some details on the most recent ones:

- A two-year-old child in Minneapolis, Minnesota. The shooter is unknown. See here for the news story.

- One person in Memphis, Tennessee. See here for the news story.

- Two people in one incident in Indianapolis, Indiana. See here for the news story.

- A guy shot by his seven-year-old son in Gratiot County, Michigan. Quote from the news story: Police say the boy took the gun from a locked case after finding the keys and accidentally shot his dad. See here for the news story.

And yet: many, many Republican politicians are passionate about keeping transgender people out of the bathroom of their choice, and even more passionate about ensuring that Americans have easy access to firearms. Go figure…

When my kid was about four years old, he went through a period where he switched the orders of certain kinds of words. It wasn’t random–this happened only with a particular kind of word formed by putting two nouns together. For example, he would say:

When my kid was about four years old, he went through a period where he switched the orders of certain kinds of words. It wasn’t random–this happened only with a particular kind of word formed by putting two nouns together. For example, he would say: