Spoiler alert: this post about the TV show The Walking Dead–which, I will note, is as popular in France as it is in the US–will tell you what happens to Carol around Season 3 or 4.

In general, it’s the stuff that surprises you that’s interesting, right? No one ever expects the arctic ground squirrel to have anything to do with computational linguistics–and yet it does: it so, so does. No one ever expects to be confronted with problems with the relationship between compositionality and the mapping problem over breakfast in a low-rent pancake house–and yet it happens; it so, so happens. (Low-rent as an adjective explained in the English notes below.) You don’t expect the zombie apocalypse to be relevant to research in computational linguistics–and yet it is; it so, so is.

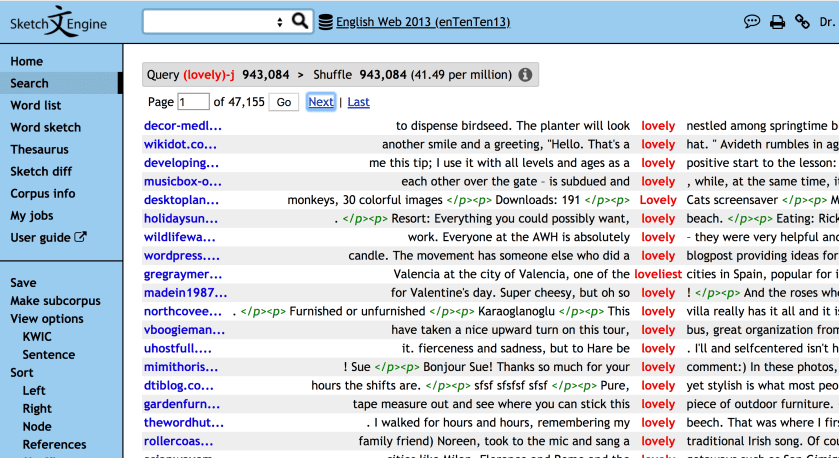

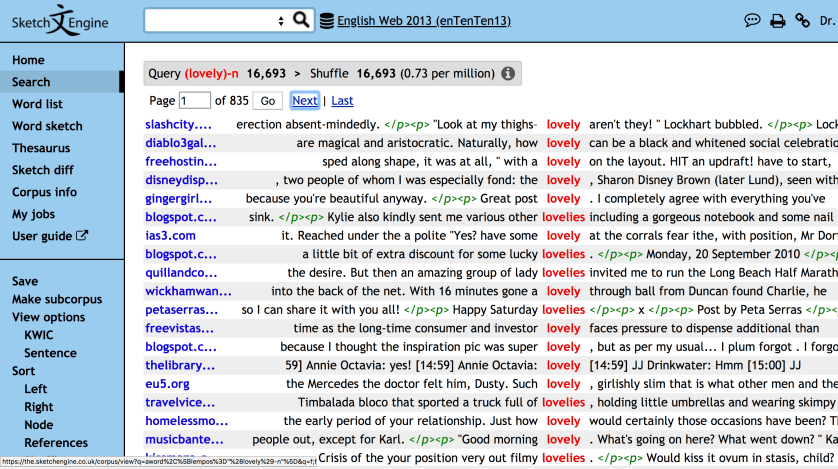

You’ve probably heard of machine learning. It’s the science/art/tomfoolery of creating computer programs to learn things. We’re not talking about The Terminator just yet–some of the things that are being done with machine learning, particularly developing self-driving cars, are pretty amazing, but mostly it’s about teaching computers to make choices. You have a photograph, and you want to know whether or not it’s a picture of a cat–a simple yes/no choice. You have a prepositional phrase, and you want to know whether it modifies a verb (I saw the man with a telescope–you have a telescope, and using it, you saw some guy) or a noun (I saw the man with a telescope–there is a guy who has a telescope, and you saw him). Again, the computer program is making a simple two-way choice–the prepositional phrase is either modifying the verb (to see), or it’s modifying the noun (the man). (The technical term for a two-way choice is a binary decision.) Conceptually, it’s pretty straightforward.

When you are trying to create a computer program to do something like this, you need to be able to understand how it goes wrong. (Generally, seeing how something goes right isn’t that interesting, and not necessarily that useful, either. It’s the fuck-ups that you need to understand.) There are two concepts that are useful in thinking your way through this kind of thing, neither of which I’ve really understood–until now.

I recently spent a week in Constanta, Romania, teaching at–and attending–the EUROLAN summer school on biomedical natural language processing. “Natural” language means human language, as opposed to computer languages. Language processing is getting computer programs to do things with language. Biomedical language is a somewhat broad term that includes the language that appears in health records, the language of scientific journal articles, and more distant things like social media posts about health. My colleagues Pierre Zweigenbaum and Eric Gaussier taught a great course on machine learning, and one of the best things that I got out of it was these two concepts: bias and variance.

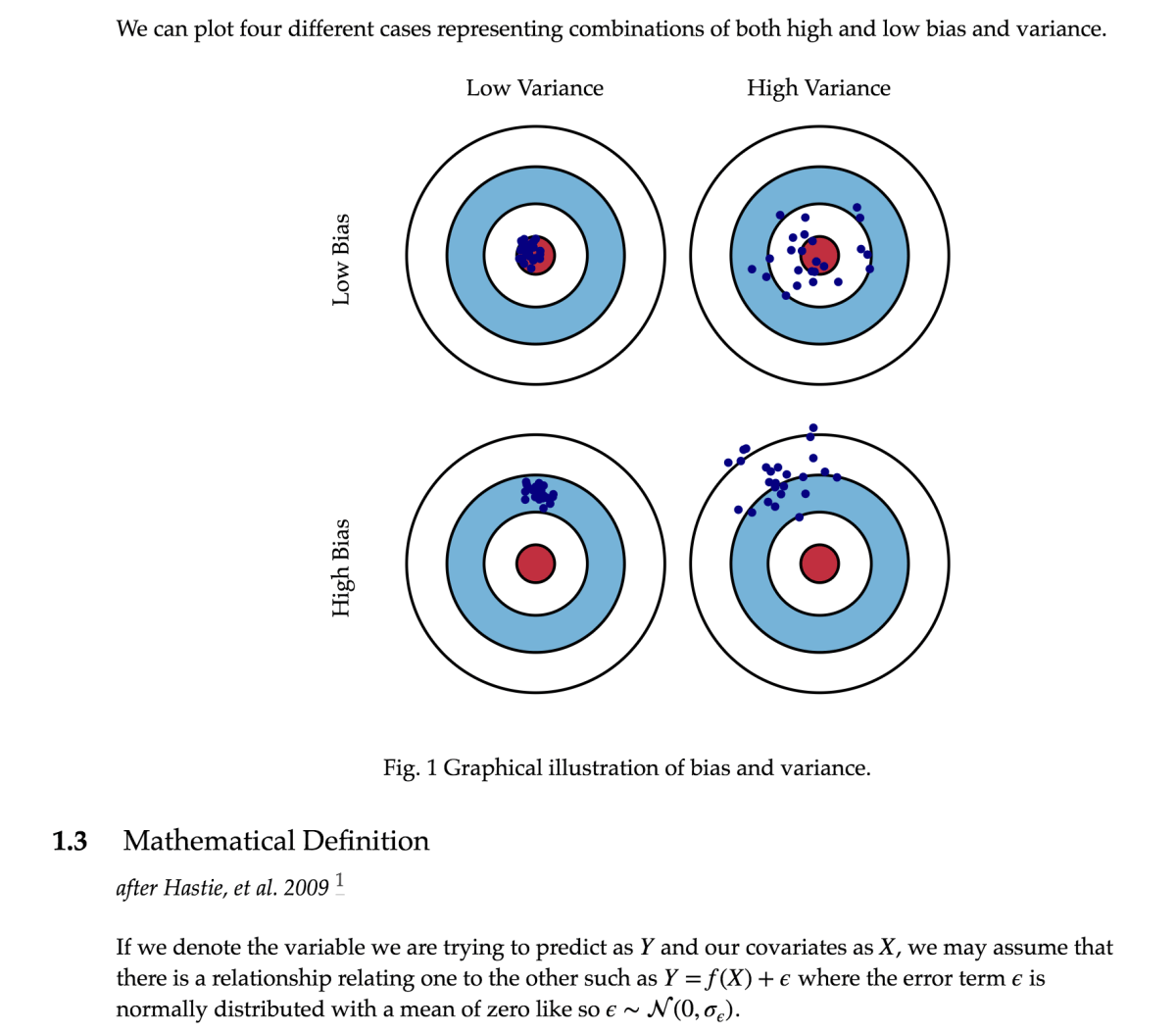

Bias means how far, on average, you are from being correct. If you think about shooting at a target, low bias means that on average, you’re not very far from the center. Think about these two shooters. Their patterns are quite different, but in one way, they’re the same: on average, they’re not very far from the center of the target. How can that be the case for the guy on the right?

Think about it this way: sometimes he’s a few inches off to the left of the center of the target, and sometimes he’s a few inches off to the right. Those average out to being in the center. Sometimes he’s a few inches above the target, and sometimes he’s a few inches below it: those average out to being in the center. (This is how the Republicans can give exceptionally wealthy households a huge tax cut, and give middle-class households a tiny tax cut, and then claim that the average household gets a nice tax cut. Cut one guy’s taxes by 1,000,000 dollars and nine guys’ taxes by zero (each), and the average guy gets a tax cut of 100,000 dollars. One little problem: nobody’s “average.”) So, he’s a shitty shooter, but on average, he looks good on paper. These differences in where your shots land are are called variance. Variance means how much your results differ from each other, on average. The guy on the right is on average close to the target, but his high variance means that his “average” closeness to the target doesn’t tell you much about where any particular bullet will land.

Thinking about this from the perspective of the zombie apocalypse: variance means how much your results differ from each other, on average, right? Low variance means that if you fire multiple times, on average there isn’t that much difference in where you hit. High variance means that if you fire multiple times, there is, on average, a lot of difference between where you hit with those multiple shots. The guy on the left below (scroll down a bit) has low bias and low variance–he tends to hit in roughly the same area of the target every time that he shoots (low variance), and that area is not very far from the center of the target (low bias). The guy on the right has low bias, just like the guy on the left–on average, he’s not far off from the center of the target. But, he has high variance–you never really know where that guy is going to hit. Sometimes he gets lucky and hits right in the center, but equally often, he’s way the hell off–you just don’t know what to expect from that guy.

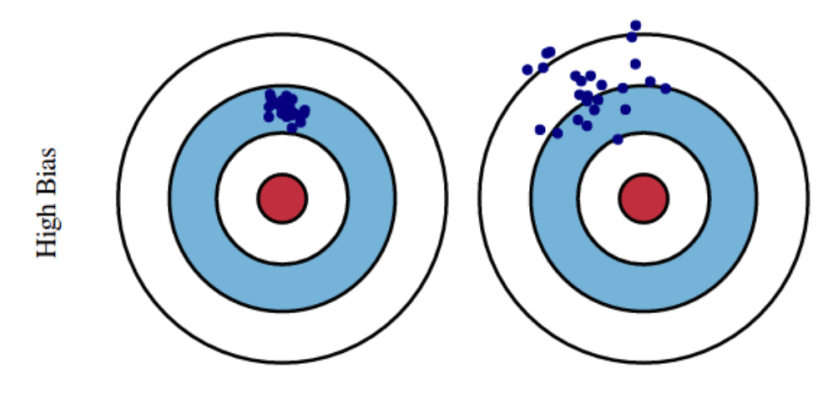

We’ve been talking about variance in the context of two shooters with low bias–two shooters who, on average, are not far off from the center of the target. Let’s look at the situations of high and low variance in the context of high bias. See the picture below: on average, both of these guys are relatively far from the center of the target, so we would describe them as having high bias. But, their patterns are very different: the guy on the left tends to hit somewhere in a small area–he has low variance. The guy on the right, on the other hand, tends to have quite a bit of variability between shots: he has high variance. Neither of these guys is exactly “on target,” but there’s a big difference: if you can get the guy on the left to reduce his bias (i.e. get that small area of his close to the center of the target), you’ve got a guy who you would want to have in your post-zombie-apocalypse little band of survivors. The guy on the right–well, he’s going to get eaten.

A quick detour back to machine learning: suppose that you test your classifier (the computer program that’s making binary choices) with 100 test cases. You do that ten times. If it’s got an average accuracy of 90, and its accuracy is always in the range of 88 to 92, you’re going to be very happy–you’ve got low bias (on average, you’re pretty close to 100), and you’ve got low variance–you’re pretty sure what your output is going to be like if you do the test an 11th time.

Abstract things like machine learning are all very well and good for cocktail-party chat (well, if the cocktail party is the reception for the annual meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics–otherwise, if you start talking about machine learning at a cocktail party, you should not be surprised if that pretty girl/handsome guy that you’re talking to suddenly discovers that they need to freshen their drink/go to the bathroom/leave with somebody other than you. Learn some social skills, bordel de merde !) So, let’s refocus this conversation on something that’s actually important: when the zombie apocalypse comes, who will you want to have in your little band of survivors? And: why? “Who” is easy–you want Rick, Carol, Darryl. (Some other folks, too, of course–but, these are the obvious choices.) Why them, though? Think back to those targets.

Low bias, low variance: this is the guy who is always going to hit that zombie right in the center of the forehead. This is Rick Grimes. Right in the center of the forehead: that’s low bias. Always: that’s low variance.

Low bias, high variance: this is the guy who on average will not be far from the target, but any individual shot may hit quite far from the target. This guy “looks good on paper” (explained in the English notes below) because the average of all shots is nicely on target, but in practice, he doesn’t do you much good. This guy survives because of everyone else, but doesn’t necessarily contribute very much. In machine learning research, this is the worst, as far as I’m concerned–people don’t usually report measures of dispersion (numbers that tell you how much their performance varies over the course of multiple attempts to do whatever they’re trying to do), so you can have a system that looks good because the average is on target, even though the actual attempts rarely are. On The Walking Dead, this is Eugene–typically, he fucks up, but every once in a rare while, he does something brilliantly wonderful.

High bias, low variance: this guy doesn’t do exactly what one might hope, but he’s reliable, consistent–although he might not do what you want him to do, you have a pretty good idea of what he’s going to do. You can make plans that include this guy. He’s fixable–since he’s already got low variance, if you can get him to shift the center of his pattern to the center of the target, he’s going to become a low bias, low variance guy–another Rick Grimes. This is Daryl, or maybe Carol.

High bias, high variance: this guy is all over the place–except where you want him. He could get lucky once in a while, but you have no fucking idea when that will happen, if ever. This is the preacher.

Which Walking Dead character am I? Test results show that I am, in fact, Maggie. I can live with that.

Here are some exercises on applying the ideas of bias and variance to parts of your life that don’t have anything to do (as far as I know) with machine learning. Scroll down past each question for its answer, and if you think that I got wrong, please straighten me out in the Comments section. Or, just skip straight to the French and English notes at the end of the post–your zombie apocalypse, your choice.

- Your train is supposed to show up at 6 AM. It is always exactly 30 minutes late. If we assume that 30 minutes is a lot of time, then the bias is high/low. Since the train is always late by the same amount of time, the variance is high/low.

- The bias is high. Bias is how far off you are, on average, from the target. We decided that 30 minutes is a lot of time, so the train is always off by a lot, so the bias is high. On the other hand, the variance is low. Variance is how consistent the train is, and it is absolutely consistent, since it is always 30 minutes. Thus: the variance is low.

Your train is supposed to show up at 6 AM. It is always either exactly 30 minutes early, or 30 minutes late. More specifically: half of the time it is 30 minutes early, and half of the time it is 30 minutes late. Assume that 30 minutes is a lot of time: is the bias high or low? Is the variance high or low?

Since on average, the train is on time–being early half the time and late half the time averages out to always being on time–the bias is low. Zero, in fact. This gives you some insight into why averages are not that useful if you’re trying to figure out whether or not something operates well. The give-away is the variance—even when something looks fine on average, high variance gives away how shitty it is.

Want to know which Walking Dead character you are? You have two options:

- Take one of the many on-line quizzes available.

- Analyze yourself in terms of bias and variance.

English notes

low-rent: “having little prestige; inferior or shoddy” (Google) “low in character, cost, or prestige” (Merriam-Webster)

I’m getting the feeling that The Penguin is a real low-rent villain to a lot of people. Like, you want him there, but not as THE boss. Not good enough to fight Batman on his own, but good enough for Batgirl and the Birds of Prey. Intriguing. 🤔

— TheFliteCast (@TheFliteCast) May 30, 2018

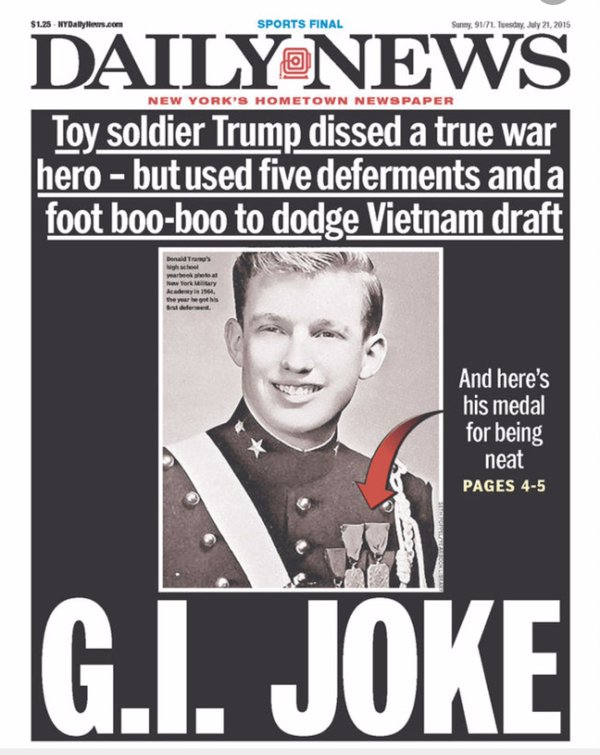

Imagine a low-rent reality TV star actually getting this much time in the Oval Office… and also, why is Kim Kardashian there? https://t.co/gaYeZcd98r

— Eddie Taylor (@tayloreddie) May 31, 2018

How is she still on TV? Why isn’t her career ruined? We run Franken out on a rail for some ancient bs but she gets to keep running her disgusting low-rent mouth?

ABC stays silent as Roseanne Barr posts racist, conspiratorial tweets https://t.co/rv018npPam via @thinkprogress

— (((Alli)))❄️ (@alli24601) May 29, 2018

to look good on paper: “to seem fine in theory, but not perhaps in practice; to appear to be a good plan.” (McGraw-Hill Dictionary of American Idioms and Phrasal Verbs) Often followed by “but…”

Argentina looks good on paper but when the games start, you’ll be seeing only Messi.

— Flowki (@gboye_baba) May 21, 2018

like many other ideologies, looks good on paper

— marwa (@mawakamel) May 29, 2018

ICYMI They Look Good on Paper, But Challenge Grants Can Be…Challenging https://t.co/Uf4tsyX2s6 #Arts #Grants pic.twitter.com/bqAvW5rS0w

— Michael Saunders (@topgovtgrant) May 24, 2018

Some of it is systemic. Ending earmarks seemed like a good idea until it removed the catalyst for compromise. And Newt’s dictum to live in one’s district looks good on paper but a lot of negative consequences.

— Blandy Fisher (@BlandyFisher) May 23, 2018

French notes

From the French-language Wikipedia article on what’s called in English the bias-variance tradeoff:

En statistique et en apprentissage automatique, le dilemme (ou compromis) biais–variance est le problème de minimiser simultanément deux sources d’erreurs qui empêchent les algorithmes d’apprentissage supervisé de généraliser au-delà de leur échantillon d’apprentissage :

- Le biais est l’erreur provenant d’hypothèses erronées dans l’algorithme d’apprentissage. Un biais élevé peut être lié à un algorithme qui manque de relations pertinentes entre les données en entrée et les sorties prévues (sous-apprentissage).

- La variance est l’erreur due à la sensibilité aux petites fluctuations de l’échantillon d’apprentissage. Une variance élevée peut entraîner un surapprentissage, c’est-à-dire modéliser le bruit aléatoire des données d’apprentissage plutôt que les sorties prévues.