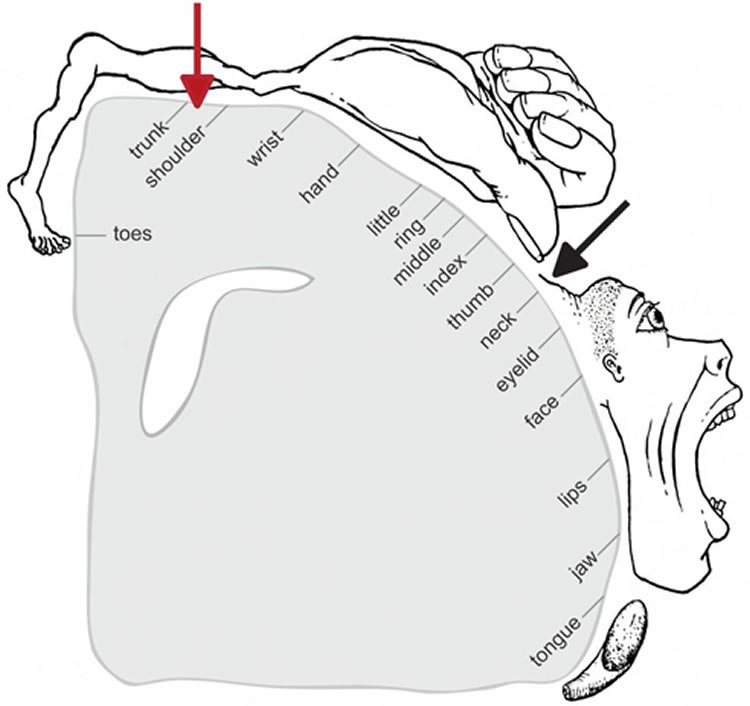

The odd guy in this picture? He’s “the motor homunculus.” The picture represents the proportions of the motor cortex that are dedicated to controlling the movements of the parts of our body whose movements we can control. The motor cortex is a part of the outer layer of the brain that is used for controlling movement. Note that not all parts of the body get equal amounts of brain dedicated to them. Some get more than others, and the relative sizes of the body parts in the picture reflect those unequal amounts. Which parts get the most?

- The organs of speech

- The hand

For decades, people like me have been showing this figure to our Linguistics 101 students and saying: you can tell how important the organs of speech are because as much of the motor cortex is devoted to them as to the control of our hands. Neurologist Frank Wilson sees it the other way around, though. His take on it: you can tell how important the hands are because as much of the motor cortex is devoted to them as to the control of our organs of speech. I like that–it’s always interesting when people see things the opposite of the way that I do.

How do we know how much of the brain is devoted to any organ? It all goes back to a Canadian-American neurosurgeon by the name of Wilder Penfield. Penfield was a pioneer of modern brain surgery. He developed a procedure for treating epilepsy by finding the region of the patient’s brain from which the unfortunate electrical storms originate, and destroying it. When you’re doing this, you don’t want to destroy a part of the brain that carries out some irreplaceable function, so Penfield developed a procedure for stimulating parts of a patient’s brain and watching what happened.

Now, I know what you’re thinking: but, you can’t see everything that might happen–it’s not like you can watch someone’s pharynx and see what part of the brain we use to control the incredibly complicated process of swallowing a bite of pizza. That’s a good point. As Dr. Peter Pressman, a neurologist at the University of Colorado School of Medicine, told me:

You’re right, Zipf–he didn’t exactly pull up each individual muscle. More like “hand, arm, throat, etc.” His was a rough map, though revolutionary at the time. It turns out that more recent work using functional magnetic resonance imaging has led to essentially the same findings–Penfield’s work was amazing.

The take-home point: whether you’re a linguist like me and want to focus on the organs of speech, or a physician who wants to focus on the hand, the amount of brain “real estate” that is devoted to each of them reflects the fact that both of them are central to being a human being.

Once a year I travel to Guatemala with Surgicorps, a group of surgeons, therapists, nurses, and anesthesiologists who spend a week donating free surgical services for people for whom the almost-free national health care system is too expensive. We bring with us specialists who can perform techniques that are beyond the skills of the local surgeons. The team includes Dr. David Kim, who specializes in hand surgery, and Dr. Courtney Retzer-Vargo, an occupational therapist who specializes in rehabilitation of the hand. These are both exceptionally rare skill sets–Dr. Kim did two separate four-year fellowships (in plastic surgery and in orthopedics) to learn his trade, and Dr. Retzer-Vargo is one of a very small number of people in the world with her specialized skills. Their work is an important part of what we do because giving someone back the ability to use their hands can mean keeping them alive in this country where most work is manual labor, and if you don’t work, you starve–as do your children.

Surgicorps members pay for their own travel, lodging, and food on these missions–and donate a week of vacation time (that’s a lot in the United States), as well as their professional services. Donations from generous people like you go entirely to covering the costs of the surgeries and pre- and post-operative care. This includes supplies, oxygen and anesthetic gases, medications, lab work, and lodging for the family members who accompany them on the long trip to the facility out of which we work. To give you some perspective: the cost of surgery for one patient works out to $250. $100 pays for four surgical packs. $10 pays for all of the pain medications that we will send our patients home with this week. Want to help? Follow this link to make a donation–you’ll be surprised at how good it will make you feel.

English notes

homunculus: a small man. The concept of tiny little people was an important but wrong idea about how exactly our physical bodies get made: before we actually knew anything about embryology, the idea that we start out as so-tiny-that-we’re-invisible fully formed humans whose development consists simply of getting bigger seemed to make about as much sense as anything else. (This idea is known as preformation–see the Wikipedia article about it for its history.)

Later conceptions of the homunculus have focussed on the extent to which we can think of it as a “representation” of the human–something that lets us think logically about people by simplifying them down to the elements that are essential to whatever it is that we’re trying to figure out about them. For example, the motor homunculus simplifies the human to a set of purposeful movements. Every representation has its benefits–in this case, the ability to have a 1200-word discussion about what the brain can tell us about the parts of humans that are most important to making them…human. Representations also have their costs. For example, representing an entire human being as a motor homunculus doesn’t let us say anything about why a human might want to move something. Life always has its trade-offs–how about trading a few of your spare dollars/euros/quetzales for the warm feeling of contributing to Surgicorps making it possible for a woman to cook her child’s tortillas in the morning, or for a man to earn the money to send that child to school? Click here to donate.

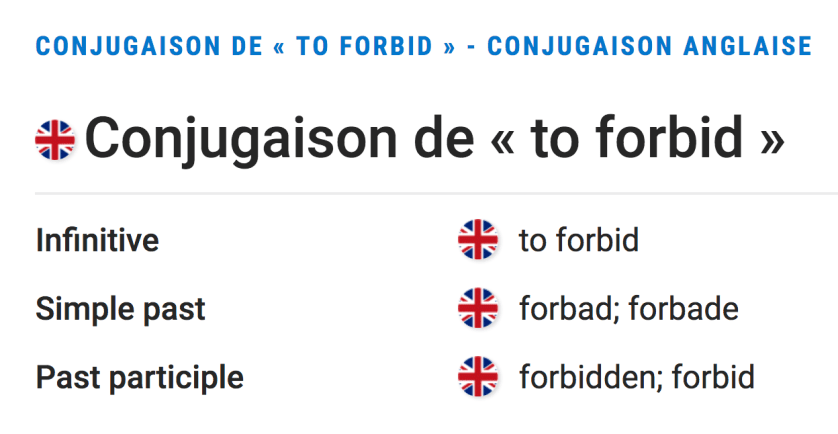

The latest evolution of the laws regarding French-language music on French radio: you can’t just play the same French-language songs over and over again. Radio stations are required to play a certain percentage of French music. Many stations have tended to fulfill that requirement by just playing the same classics repeatedly, which makes no one happy. The radio stations’ excuse: there just isn’t that much good new French-language music.

The latest evolution of the laws regarding French-language music on French radio: you can’t just play the same French-language songs over and over again. Radio stations are required to play a certain percentage of French music. Many stations have tended to fulfill that requirement by just playing the same classics repeatedly, which makes no one happy. The radio stations’ excuse: there just isn’t that much good new French-language music.

…and its antonyms, also from

…and its antonyms, also from

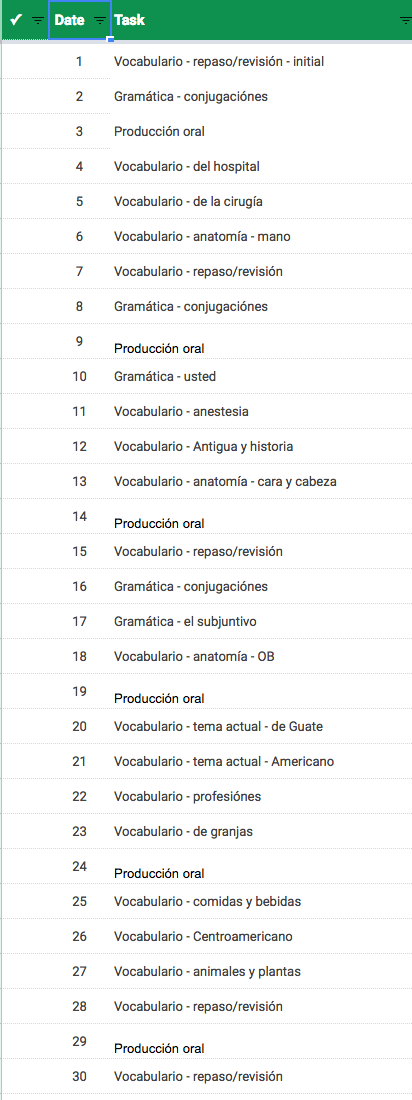

So, you take all of those individual things to work on, mix ’em up to give yourself a little variety in your daily study. Prioritize things in a way that makes sense for what you plan to be doing with the language–I have a day in there for learning the vocabulary of food and beverages, but that’s more so that I can translate the menu for my fellow volunteers than for the actual volunteer work, so it wouldn’t make sense to be working on that first, and I don’t. Mix in some review days–review is essential, and you don’t want to do it all at the end. Boum, as the French kids say–a month’s-worth of work. I’ll start it on July 1st, and I’ll finish it sitting in the plane on the way to Guatemala on the 30th. If I screw up and miss a day? Not the end of the world–I’ll make it up. If I just can’t stand anesthesia vocabulary on July 11th? No problem–I’ll just switch a couple days around. Is the list intimidating? No–the opposite. I know that if I prepare, everything will probably go fine, and I know that if I work my list, I’ll be prepared–so, it’s actually reassuring, not intimidating.

So, you take all of those individual things to work on, mix ’em up to give yourself a little variety in your daily study. Prioritize things in a way that makes sense for what you plan to be doing with the language–I have a day in there for learning the vocabulary of food and beverages, but that’s more so that I can translate the menu for my fellow volunteers than for the actual volunteer work, so it wouldn’t make sense to be working on that first, and I don’t. Mix in some review days–review is essential, and you don’t want to do it all at the end. Boum, as the French kids say–a month’s-worth of work. I’ll start it on July 1st, and I’ll finish it sitting in the plane on the way to Guatemala on the 30th. If I screw up and miss a day? Not the end of the world–I’ll make it up. If I just can’t stand anesthesia vocabulary on July 11th? No problem–I’ll just switch a couple days around. Is the list intimidating? No–the opposite. I know that if I prepare, everything will probably go fine, and I know that if I work my list, I’ll be prepared–so, it’s actually reassuring, not intimidating.

Descending from the aforementioned elevation on a Sunday-afternoon walk the other day, I came across Grégory Jacob and a truly delightful place to buy non-touristy stuff in Montmartre.

Descending from the aforementioned elevation on a Sunday-afternoon walk the other day, I came across Grégory Jacob and a truly delightful place to buy non-touristy stuff in Montmartre.