I was sitting in on a class on lexical semantics a couple years ago. Lexical semantics is the study of the meanings of words. What that means: think about the difference in meaning between The fairy godmother waved her baguette and The fairy godmother’s baguette waved her. On some level, we can describe the difference in the meanings of those two sentences as coming from the facts that (a) an English sentence with a subject, a verb, and an object has the meaning that the subject did something to the object, and (b) the two sentences have different subjects and objects. That’s not about lexical semantics, or the meanings of words–we could call that sentential semantics, perhaps.

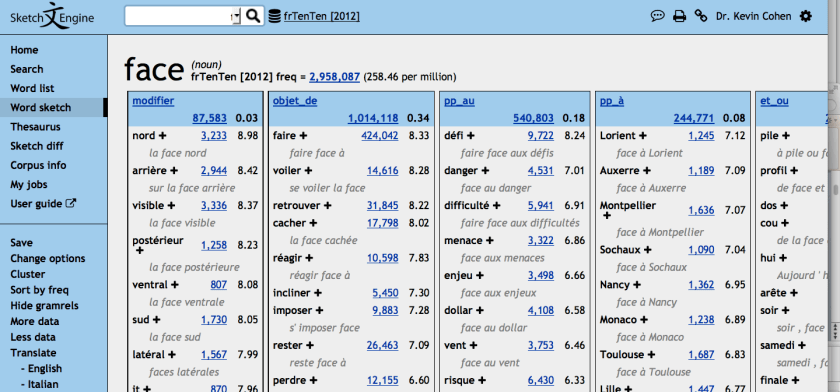

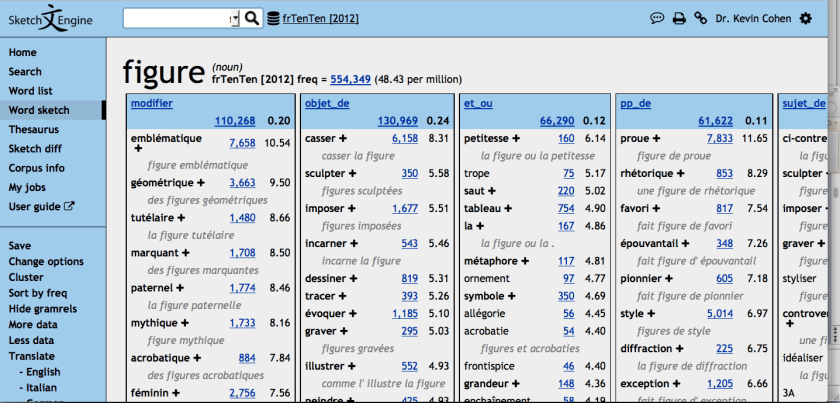

In contrast with that, consider these sentences:

- Bobo swept the floor.

- Bobo swept.

- Bobo broke the glass.

- The glass broke.

In the case of sentence (2), Bobo did the sweeping. In the case of sentence (4), though, the glass got broken. To put it another way: in (2), the subject of the sentence carried out the action of the verb, while in (4), the subject of the sentence underwent the action of the verb. This difference in meaning doesn’t have anything to do with the structures of the sentences, as was the case with the fairy godmother and her baguette–this is about the difference in meaning between sweep and break. (For example: break involves a change in the state of something. Sweep, in contrast, doesn’t.) That’s lexical semantics–the study of the meaning of words.

So, back to that class: one of the folks in it started complaining about how deficient both of these approaches to thinking about semantics are. Sure, we can formalize the meanings of words in a way that captures the differences in meaning between sweep and break. We can formalize the meanings of sentences in a way that captures the differences in meaning between the two fairy godmother/baguette sentences. But, what about the rest of the meaning? How does the meaning of sweeping change, depending on whether Bobo is a property owner, or a member of the proletariat? What does it mean that the fairy godmother is a godmother, and not a fairy godfather? Indignation was widely shared.

Actually, this is a misunderstanding of what semantics is, versus semiotics. Semantics is (in my version of the world) about how language means things. Semiotics is about how meaning gets meant, in general. If I say to you Bobo swept the floor, that’s got one kind of meaning. If I give you a single red rose on our third date, that means something, too. How does Bobo swept the floor mean what it means? I can talk about that–we just did. How does that single red rose on our third date mean what it means? I don’t have a clue. The meaning of the sentence: that’s semantics. The meaning of the single red rose: that’s semiotics. One way to think about why to study linguistics: suppose that you’re interested in the question of meaning. You could think of language as the system of meanings that is the easiest to study. So, if you’re into semiotics in general, then semantics might be a way to get a handle on what seems like a very large problem. On that picture of the universe, semantics is a subset of semiotics. (I don’t mean to imply that I think that we totally understand how meaning works in language, either–I don’t. Indeed, we’ve had a number of posts on this blog about controversies and problems with representing the meanings of words.)

All of this came to mind recently when I came across a couple news stories on the use of emojis to convict people for various and sundry crimes. (See below for a discussion of the differences/similarities between the English constructions a couple and a couple of.) For those of you who have been in a digital wasteland for the past few years, here is a definition of emoji from Google:

It is amazingly easy to find examples of the appearance of emoji in criminal cases. I Googled this:

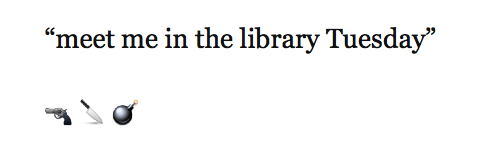

…and got tons of results. A 12-year-old girl in Virginia is facing charges of threatening a classmate for sending her this message on Instagram:

Last year, a 17-year-old male was arrested and charged with making terroristic threats for posting these emojis of a police officer and some guns on Facebook (a grand jury later declined to indict him):

Picture source: http://www.cnet.com/uk/news/teen-arrested-after-alleged-facebook-emoji-threats/

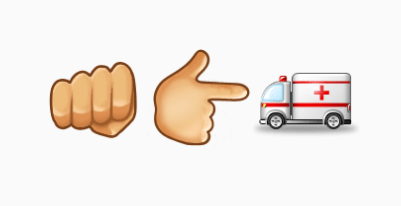

David Fuentes and Matthew Cowan of South Carolina were arrested and charged with stalking after they sent these emoji to someone whom they’d beaten up the month before:

Smiley-faces show up repeatedly in court cases, both criminal and civil. Anthony Elonis’s case went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. A quote from an article by Karen Henry and Jason Henry on the Law360 web site:

The defendant in Elonis v. United States had argued that his conviction for posting threatening communications on Facebook should be reversed in part because the presence of emoticons in some of the posts made them “subject to misunderstandings” and not as threatening as they would otherwise have been. For example, one of the defendant’s posts said that his son should dress up as “matricide” on Halloween, perhaps by wearing a costume of her “head on a stick.” He followed that post with an emoticon of a face with its tongue sticking out. He argued that the emoticon signaled that he was joking…

In a civil lawsuit, Universal Music Corp. tried to argue that the person who was suing them hadn’t really been injured by them, presenting as evidence the claim that an emoji that she had used in an email in which she corresponded with a friend about the case showed that she didn’t really feel that she’d actually been injured (same source):

…the evidentiary value of emoticon/emoji evidence was examined fairly recently in Lenz v. Universal Music Corp. (widely referred to as “the Dancing Baby” case). In that case, plaintiff Stephanie Lenz moved for summary judgment on six affirmative defenses asserted by Universal in response to Lenz’s copyright claim. Of particular relevance, Universal argued Lenz alleged in bad faith that she had been “substantially and irreparably injured” by its takedown notice. To support this argument, Universal proffered an email exchange between Lenz and her friend. In that exchange, the friend writes, “love how you have been injured ‘substantially and irreparably’ ;-).” Lenz, in turn, responds, “I have ;-).”

Universal contended that Lenz’s use of the “winky” emoticon signified that she was “just kidding.” Lenz countered that her use of the “winky” emoticon replied to the “winky” in her friend’s email, which basically was teasing Lenz about using lawyerese in her complaint — i.e., “substantially and irreparably injured.” The court sided with Lenz, finding Universal’s proffered evidence insufficient to prove Lenz acted in bad faith and granting summary judgment in Lenz’s favor on that affirmative defense.

There are multiple legal issues involved in these emoji cases, some of them just really basic procedural stuff. If you’re reading an email out loud in a court case, do you have to read any accompanying emojis out loud? If so: how? Back to the Elonis case in the Supreme Court–I’m going to add in a clause that I omitted in the earlier quote (same source again):

… one of the defendant’s posts said that his son should dress up as “matricide” on Halloween, perhaps by wearing a costume of her “head on a stick.” He followed that post with an emoticon of a face with its tongue sticking out. He argued that the emoticon signaled that he was joking, but his wife interpreted the tongue sticking out in that context as an insult.

This issue–read them out loud, or not, and if so, how–came up in a case that you may have read about–the “Silk Road” case against Ross Ulbricht for running a huge “dark Web” site for selling illegal stuff:

I write about this here and now in part because there have recently been a couple of similar cases in France (see here for Bilal Azougagh’s case), and I suspect that the French courts will do a much better job of hashing out the theoretical issues behind this than the US courts have so far. In reading about this issue in the US, I’ve come across “useful” observations like the claim that unlike words, emoji don’t have clear and unambiguous meanings–total linguistic bullshittery, as words don’t have clear and unambiguous meanings in any human language that I’m aware of. These are difficult and (to me) interesting questions/problems, and I look forward to seeing the French legal system do a much better job of getting at the underlying philosophical issues than the American courts have so far, that being something that the French have much more of a propensity for (and much better educational preparation for) than Americans do.

French notes (scroll waaaay down for the English notes)

For some random Zipf’s-Law-induced vocabulary items, let’s look at the French Wikipedia page on emoji:

Vocabulary item: I’ve been trying to get straight on the many uses of the verb répandre, and here it is! (See above about words not having clear and unambiguous meanings.) Two of the many potential meanings of se répandre that are possibly relevant here (from WordReference.com):

- se répandre (s’etendre) (sur?): to spread.

- se répandre (envahir, se disséminer) (dans?): to spread out, to invade.

I’d also like to know the genders of emoji and émoticône. Let’s see what evidence we can find:

Certains rather than certaines suggests that emoji is a masculine noun. Emoticône is easier to figure out:

Une, so: feminine noun.

Back to the lexical semantics lecture: I followed my classmate’s rant with my own, along the lines of the semantics/semiotics split that I talk about above. The professor gave me an odd look when I suggested that it would mean something if I gave her a single red rose, but otherwise, there were no repercussions that I know of. Watch this space for further developments.

English notes

I used the expression a couple a couple times in this blog post. See these links for some discussions of the use of a couple versus a couple of:

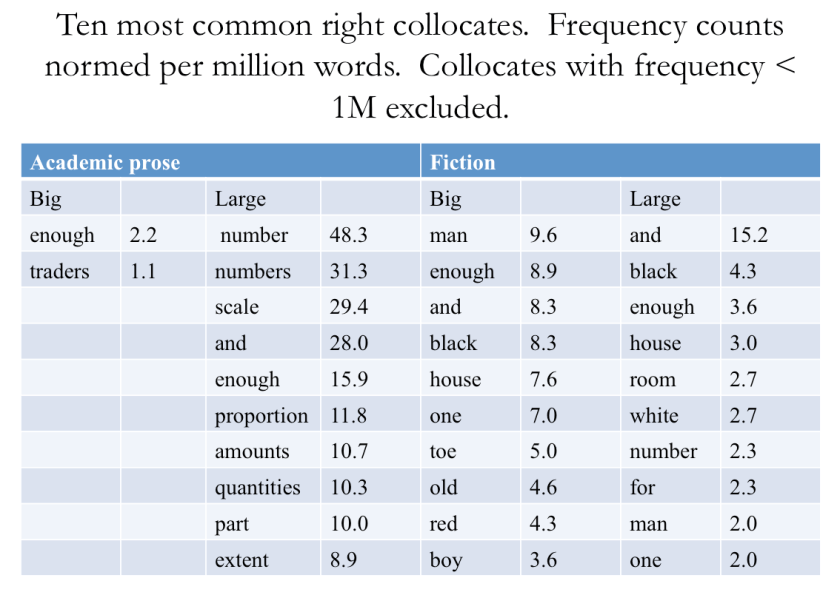

It’s complicated–there are situations where either one is fine, and situations where only one of the two is fine. Here is a little data.

A couple is mandatory:

- I have a couple (fine)

I have a couple of(not OK at all)

A couple of is mandatory:

I have a couple them(not OK at all)- I have a couple of them (fine)

Either is fine (although I prefer a couple, personally):

- I have a couple apples (fine)

- I have a couple of apples (fine)

A couple of is mandatory:

I have a couple them(not OK at all)- I have a couple of them (fine)

When my kid was about four years old, he went through a period where he switched the orders of certain kinds of words. It wasn’t random–this happened only with a particular kind of word formed by putting two nouns together. For example, he would say:

When my kid was about four years old, he went through a period where he switched the orders of certain kinds of words. It wasn’t random–this happened only with a particular kind of word formed by putting two nouns together. For example, he would say: