We’ve recently been talking about ambiguity. Ambiguity, from a linguist’s perspective, is the situation of having more than a single possible meaning, and as we’ve seen, there are MANY ways to be ambiguous.

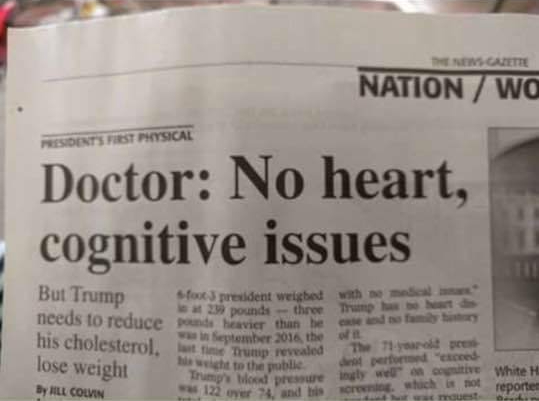

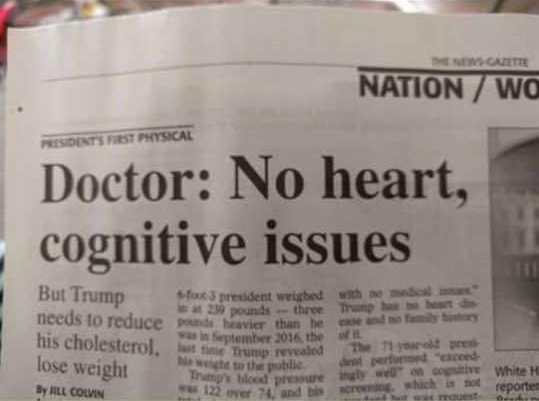

Here’s a nice example. It comes from the renowned linguist and cognitive psychologist Steven Pinker. Like many linguists, he collects ambiguous headlines. They are not at all difficult to find, but some are cooler than others. Here’s his current favorite:

What can one say about this? From a linguistic perspective, what are the possible interpretations?

- There is some doctor who does or does not have things going on with respect to his or her heart–we’ll get into what those things could be momentarily.

- There is some doctor who said something about someone who does or does not have things going on with respect to his or her heart.

Now, the second interpretation is the intended one, so let’s go with it for the rest of the discussion. (We’ll talk later about what happens if we don’t.) What’s the issue with the rest?

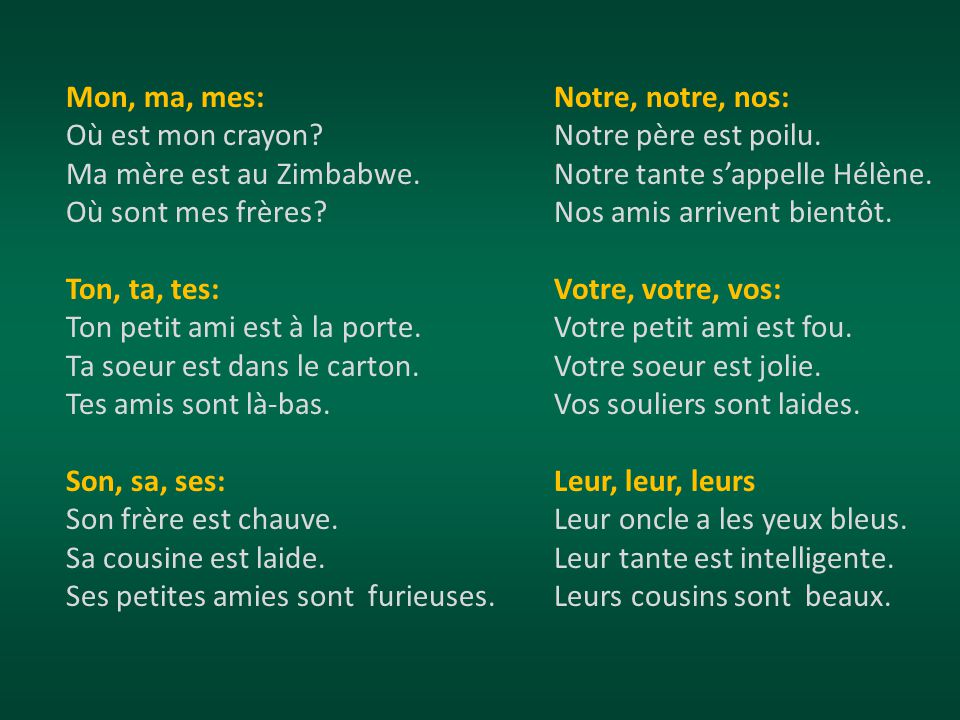

- One interpretation is that the comma indicates what’s called a kind of coordination or conjunction: it corresponds to or, and the intended meaning is that the person who’s being talked about does not have heart or cognitive issues. (That’s not the full story here–more below.)

- Another interpretation is that the comma indicates a new clause. In this case, it would correspond to the doctor saying that the person under discussion does not have a heart, and also has cognitive issues.

How many possible meanings so far? We’ve listed four, but it’s a big underestimate.

Why does Pinker like this one so much? Because that last interpretation says this: Trump has no heart, and he also has cognitive issues. That jives pretty well with what I would say, personally, and apparently Pinker, too–so, yeah, I would love to see that in a newspaper (assuming that his cognitive issues didn’t lead to him nuking somebody in a petulant frenzy before he could be (legally) put out of office.

Now: we’re not done yet. Here are some remaining issues:

- What is the scope of issues? Are we talking about heart issues and/or cognitive issues, or are we talking about cognitive issues, and some unspecified thing about the heart?

- What is the scope of no? Are we talking about no heart and no cognitive issues, or are we asserting something about cognitive issues, plus something about there being no heart involved in some way?

- What does heart mean? Are we talking about an anatomical organ, or are we talking metaphorically, where heart can mean something like inherent kindness? Or maybe we’re talking metaphorically, but where the metaphorical meaning of heart is something like courage? (See this video for the meaning of “heart,” “heart checks,” and “showing heart” in prison.) Does it mean a seasonal check on the core of timber? (Seriously–check it out on DictionaryOfConstruction.com.)

- What does issue mean? We actually had a blog post that was primarily on that question, in the context of analyzing Henry Reed’s poem Returning of Issue.

So: how many interpretations of that headline are there? A low estimate would be two for each of the questions that we thought about above, so each one of those points doubles the number of possible interpretations. That’s 2 to the 8th power: 256 possible interpretations. You found another point of ambiguity? You just doubled the number of interpretations again, to 512. (Go ahead–find another one, and tell us about it in the Comments section.)

Here’s a question for you: of the 256 possible interpretations, just two of them seem to be the most obvious ones:

- The one where the doctor is talking about someone else, where issues modifies (technically, “has scope over”) both heart and cognitive, the meaning of heart is the anatomical organ, and no modifies both of heart issues and cognitive issues.

- The one where Trump is unkind and has cognitive issues.

Why?

…and here’s an observation for you: my profession is about getting computers to differentiate between the possible interpretations in biomedical journal articles and in health records, finding the one intended interpretation out of all of the possible ones. I don’t expect to have it solved any time soon. 🙂