I’ve been struggling to get up the hill on the way to work lately. I decided that this was due to my proteinless French breakfast of coffee, bread, and Nutella, and stopped at the little store just outside the train station and picked up a can of sardines for after the climb. Zipf’s Law being what it is, this set off a three-day struggle to figure out how to read the label on the can. I spend a lot of time in France trying to differentiate and remember the meanings of words that look alike, and this was one of those occasions. After three days of this, I still don’t have it all figured out. At its base, this is an issue of various and sundry words that look or sound like forms of the word arrêter. Read on if you want to feel my pain.

arrêter: The basic meaning of this verb is “to stop,” which is simple enough, but there are some subtleties involving the pronominal form of the verb (s’arrêter) and “direct” versus preposition-specific forms of the verb.

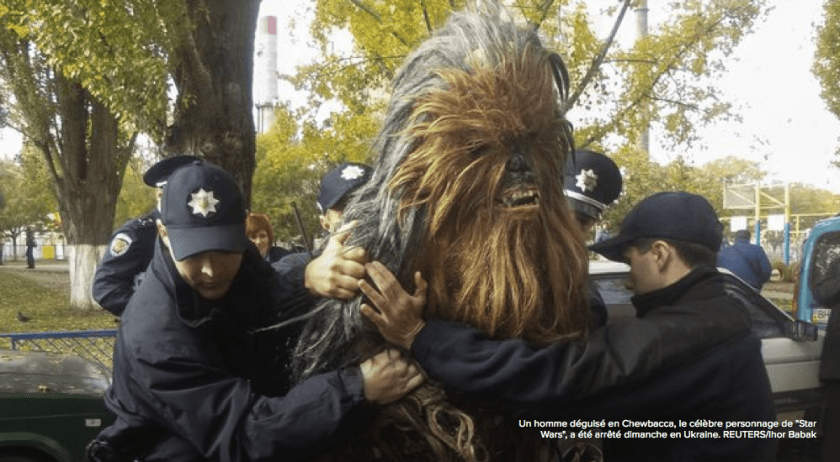

arrêter: The verb can also mean “to arrest,” as in taking someone into police custody. Scroll down–this picture is too good to shrink.

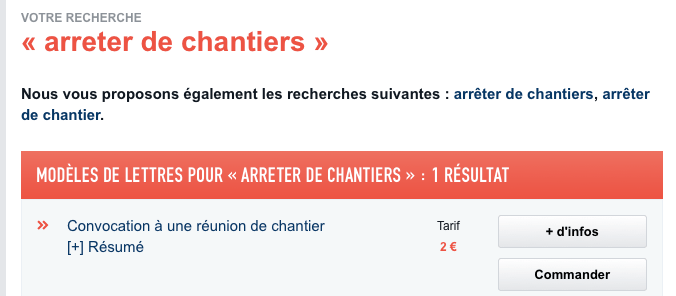

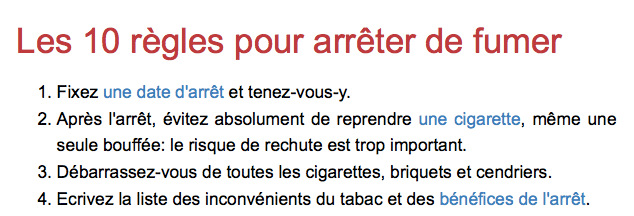

arrêter de: this is followed by an infinitive, and would translate as “to stop verbing.”

l’arrêt: a stop, as in a bus stop, a work stoppage, etc. Also: a decision, as of a court.

Medical-care-specific: The verb arrêter can have a very specific meaning, which is to put someone on sick-leave. The subject of the verb presumably has to be someone who is capable of putting you on sick-leave. (Linguistics geekery: this kind of behavior, where the meaning of a verb can change substantially depending on the subject and/or object of the verb, is probably best accounted for by the Generative Lexicon theory, pioneered by James Pustevosky of Brandeis, and more recently elaborated by Elisabetta Jezek of the University of Pavia.)

However, just because “doctor” is the subject doesn’t mean that the verb necessarily has that meaning:

Here, the m’ is an indirect object pronoun, and it’s la pilule (“The Pill”) that is the direct object. (That bit of extra information probably doesn’t help much–sorry!)

l’arrêté (n.m.): this is a noun meaning “order” or “decree.” It shows up quite a bit in official communications of various and sundry sorts–see below.

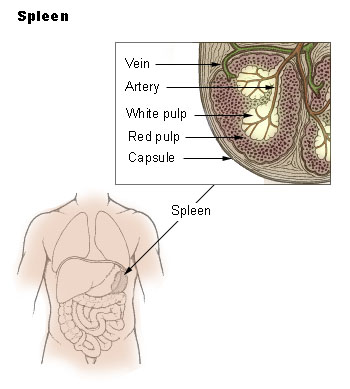

l’arête (n.f.): another noun, meaning (among other things) “fishbone.” This is the one that finally drove me over the edge to look up all of these various and sundry meanings. I would’ve gotten this one a lot quicker, but it took me, like, three days to realize that there was only one R.

- un arrêt: a judgement or decision, in a legal context. Un arrêt de la cour: a court ruling.

- un chien d’arrêt: a pointing breed of dog.

être à l’arrêt:

- to be on point (of a dog).

Le chien est à l’arrêt:

- the dog is on point. (Thanks to native speaker

- for these.)

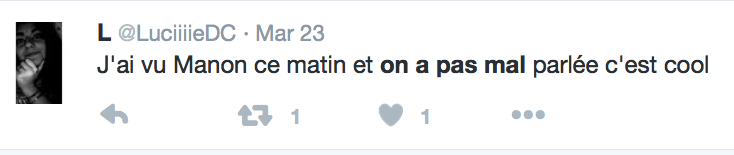

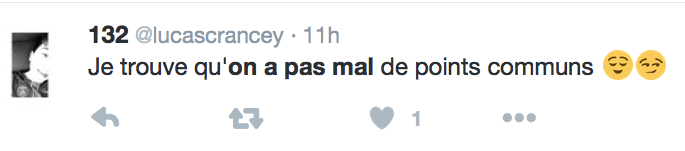

Even after this in-depth investigation, I don’t understand all of the various and sundry permutations of these words with their as, their rs, their ês, and their ts. Here’s an example that I came across–I have no clue whatsoever what it means. (Various native speakers have suggested that it’s an error–see the Comments section.) PS: in the end, sardines aren’t that great of a solution to the whole I-need-more-protein problem–they smell, and I do have office mates. Time to ramp up my already-enormous cheese consumption yet again, perhaps…