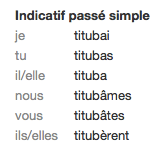

The verb to hustle can have a couple different meanings in English, one of which is good, and one of which is bad.

- The good meaning of hustle: behaving with what the Merriam-Webster dictionary calls “energetic activity.” Someone who’s hustling in this sense is working hard; moving around a lot; expending a lot of effort, in a good way. If you want to get into a good college, you’re going to have to hustle this year. She really hustled, and she finished the program early. Commonly said to athletes: Come on, get out there and show some hustle!

- The bad meaning of hustle: “to sell something to or obtain something from by energetic and especially underhanded activity…to lure less skillful players into competing against oneself at (a gambling game)” (Merriam-Webster dictionary again). (“Underhanded” means through trickery or dishonesty.) This is basically the same meaning as to con someone–to trick them out of money—and a hustle (it can be a noun, too) can also be known as a con, or a con game, or a confidence game (which is where the shorter name comes from).

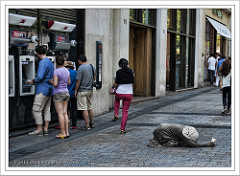

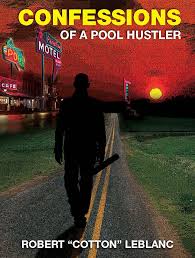

A pool hustler is more or less the archetype of the hustler. Pool hustlers are excellent pool players. They trick people into betting with them by pretending to not be very good, and then reveal their true skill after the bets are laid. Picture source: http://bankingwiththebeard.com/?p=1425. You will find people running hustles (or cons) pretty much everywhere you go in the world, including places where there are no tourists–people try to hustle the locals, too. But, there are some hustles that are especially common in Paris, and some that I haven’t seen anywhere else. Read on for descriptions of how they work.

The common Parisian hustles

There are some pretty common hustles in Paris, and you will probably see at least one of these if you go to any of the famous tourist sites (and you totally should–I firmly believe that everyone should do as many of the stereotypical Paris tourist things as they can, at least once). Here are the things that you’re likely to see:

- The ring hustle

- The friendship bracelet

- 3-card Monte, or whatever

- The fake petition

- The fake deaf/mute

What I find especially interesting about all of this is that there is a system in operation here–an ecosystem, if you will. We saw in a previous post that there are specific kinds of beggars that do their thing in specific areas–the guys who make speeches on subways, the Roma ladies on the Champs Elysées, etc. There’s a similar kind of system in effect with regard to hustles–different groups more or less own specific hustles, and specific hustles are associated with specific areas of Paris. In addition, there are some common types of robbery: picking pockets, and snatch-and-runs. You can find countless web pages on the subject of how to avoid getting your pocket picked in Paris, and I won’t belabor the point. Of course, the vast majority of people will have no trouble with thieves at all (although I do have a friend who had his pocket picked twice during the same visit to our fair city–just rotten luck). The only thing that I would add to the bazillion web pages on not getting your pocket picked in Paris is this: don’t lay your cell phone on the table while you’re talking, or even while you’re reading emails or something–you should have it in your hands at all times, and if you’re standing in the middle of the sidewalk looking at it, you should have it tightly in your hands. Now that cell phones can be worth hundreds of dollars, picking them up off of a table on the patio outside of a cafe, or even snatching them out of someone’s hands, and running off is unfortunately a thing.

The ring hustle

The basic principle of this is that you and someone else find a gold ring at that same time, and they try to convince you that you should give them money in exchange for “their share” of the ring. The ring is a piece of crap. I once had the same guy try this one on me twice within twenty minutes on the same bridge. He tried it as I was crossing the bridge in one direction, and then again as I crossed back the other way–I think he might not have been very focussed that day. How exactly you both happen to discover this thing at the same time can vary, and how exactly the person tries to talk you out of your money can vary, but the basic principle is the same: ring, money.

This is pretty much a Roma thing, as far as I can tell. In Paris, you should especially watch for this one on the bridges over the Seine–why, I have no clue.

The friendship bracelet

The basic principle of this is that you are offered a free friendship bracelet by a friendly guy. In fact, you don’t even have to accept it–he’ll just grab your hand and start putting it on you, if you don’t avoid him well. Once it’s on you, it’s no longer free, and he demands a lot of money for it. Part of what makes this work is that the guy uses the bracelet as a handle to keep you physically under control–in the best (for him)/worst (for you) case, by using your finger to make the thing for you (see below). This is almost entirely a West African thing, and the hotbed is the steps of the Sacré Coeur basilica. Why? I have no idea.

The shell game

Make no mistake: the people who are doing the things that I’m describing on this page are scumbags. They steal–they just mostly don’t use violence to do it. In the case of the shell game (and its card-based relative, known as 3-card Monte in English) though, I have to admit that I find it somewhat difficult to feel as much empathy for the victims as I usually do. This is despite the fact if you fall for this one, you are probably going to lose much, much more money to this con than you would to anything else on this page. More on that in a minute.

The basic idea here is that the guy running the con has three cups. He’ll put something under one of them, move the three cups around, and then give free money to anyone who can guess which cup it’s under. It’s easy–you see the guy just giving money away. He gets you to put up some of your own money. You do, and all of a sudden you guess wrong. I watched a guy doing this a couple weeks ago–he was trying to get people to put up 100 euros.

The reason that I find it harder to empathize with people who get caught by this one than with people who fall for the other cons that I describe on this page is this: people have been pulling this shit for over 2,000 years. The shell game existed in Ancient Greece. It was already all over Europe in the Middle Ages. How can people not have heard of this?? I have no clue.

This is mostly a Roma thing, although I saw what appeared to be a South Asian guy doing it once. I’ve often seen it in Paris in the near surroundings of the Eiffel Tower–mostly on the Iena Bridge, and I don’t remember seeing it anywhere else. I have to say that this is the rarest of the Paris hustles–it requires a fair amount of set-up, and a number of confederates (when I was watching the other night, there were four adult males involved, one of whom was pretending to be a stranger playing the game, and the other two of which were hanging around discreetly nearby and watching–if you get pissed and try to take your money back from the guy, good luck duking it out with four adult males at the same time). It’s also super, super illegal, so although the potential benefits to the crooks are large, the potential costs are, too.

The fake petition

The basic idea: a pretty girl asks you to sign a petition. For no reason that I understand, it’s typically about better treatment for the deaf, and indeed, she pretends to be deaf. Once you’ve signed, you’re pressured to donate some money for the cause. She’s not deaf, nor are the other pretty girls who are with her with their own identical petitions, nor are the other pretty girls who you’ll see in other parts of Paris with their identical petitions on the same day. In a variant of the usual approach, while you’re signing the petition, someone is picking your pocket. This is mostly a Roma thing, and it’s common in front of Notre Dame and the surrounding areas, as well as the Hôtel de Ville.

The fake deaf-mute

This one happens on the local trains. A guy gets on board and walks up and down the train leaving little printed notes on the empty seats, explaining that he is deaf/mute/whatever, and do you have a little spare change? These guys are actually the least objectionable of all of the folks who I describe on this page–they don’t pester you. I saw a variant of this in Slovenia last week–the guy went through restaurants, leaving his little cards (trilingual–Slovenian, Italian, and German) on the tables, with a couple little trinkets that you were invited to buy.

The free flower/rosemary/herb of some variety or another

This is a variety of the here’s-something-free-that-suddenly-isn’t-free-anymore scam. I haven’t actually seen it in France, but I include it for completeness. In the Spanish version, it’s a little old lady on the steps of a church. If you don’t give her money, you are threatened with a Roma curse. (I actually find this somewhat charming–who gets cursed anymore?) I ran into a wonderful version involving an attractive woman in an extremely short dress in Turkey. Wonderful mostly not in that there was an attractive woman involved, but in that I was able to participate in the ensuing mess with only as much knowledge of Turkish as you get from the Pimsleur course:

There are indeed lots of guys wandering through the restaurants in tourist areas trying to sell you roses in Paris, but there’s no deception involved (at least, not that I’ve experienced, and I did double-check this with a local), and they’re typically not pushy (pushiness being an identifying feature of hustling in its bad sense–see above)–it’s not really a hustle (in the bad way), per se. I would call it the good kind of hustle–see a later post on the subject.

Videos of these folks in action

Here are some videos of these folks in action. I didn’t shoot these–more on why you shouldn’t try to, either, below. This is all stuff that I found on YouTube.

First, some pretty good footage of the friendship bracelet thing, shot in Italy. I haven’t seen the shoulder thing in France, but the principle is similar–the guy does whatever he can to establish a situation such that you are physically in possession of the bracelet. Other interesting points: notice the repeated use of a question that the guys know you’ve been answering automatically several times a day, and that it feels rude not to respond to: where are you from? It’s also a question that lets the guy quickly establish some sort of rapport with you. Another cute thing about this: notice the guy who keeps saying waka waka? That’s not a Sesame Street thing–it’s Cameroonian English (Cameroon is a country in West Africa with two official languages: French, and English.) It’s an exhortation–literally, it means something like “walk while working.” You can hear it in Shakira’s theme song for the 2010 soccer (football, sorry) World Cup.

There’s a lot of dead footage in the beginning of this next video, but right about at the middle there’s some great footage of an attempt to snatch someone’s bags as they’re boarding the subway. It’s a good view of how proximity to the door of a metro car is used to snatch stuff. Atypically, these young ladies were unsuccessful, but you get the picture of how it works.

Don’t try to film these guys in action

Don’t try to film any of this shit! I think it’s great that people can get footage of this kind of shitty behavior and then post it on YouTube for the edification of the rest of us, but photographing or shooting video of a criminal in action is an excellent way to get punched a couple times and to have your expensive cell phone stolen. Déconseillé, as we say in these parts.

Final words: don’t berate yourself, don’t be scared, don’t let it ruin your vacation, and don’t feel obliged to be polite to these folks

If you get snagged by the evil kind of hustler, it’s really easy to berate yourself afterwards for being a fool, a sucker. Don’t. Unless you go for the shell game, you’re not–these people are pros, they make their living this way. This kind of incident can really sour you on wherever you happen to be, too, and really cast a cloud over your trip. Don’t let that happen! These people are the tiniest, tiniest, tiniest, tiniest fraction of the people you’ll meet, and they’re pretty unlikely to be Parisians, or even French. Plus, unless you fall for the shell game thing, these guys don’t actually take that much money off of you, and there are far, far more expensive hustles being worked in China and Turkey right now. It’s also worth pointing out that there is very little violent crime in this country. In America, you can get shot to death in a road rage incident pretty much any day of your life–it’s just a fact of life in our gun-cursed country. In France, you might get robbed, but the chances of your being physically attacked if you’re not visibly Jewish are very, very low (and even if you are visibly Jewish, your chances of being physically attacked are still pretty low). So, use some common sense, be aware that all you have to do is ignore these people, or in the case of a friendship bracelet guy handing you something, feel free to drop it on the ground and walk off without a word. The truth is, these people are trying to rip you off, and you do not owe them one single tiny bit of the typical American friendly politeness to strangers. You should also realize that there are plenty of people out there on the streets of Paris trying to make a living via the good meaning of “hustle”–just getting out there and working long hours in all kinds of weather, perhaps not totally within the law, but not hurting anyone, either. We’ll talk about those in another post.

- un tour de passe-passe: one French expression for the shell game–can native speakers help me with others?

- l’arnaque (n.f.): rip-off, swindle, fraud, con.

- arnaquer qqn: to rip off, swindle, or con someone.

- c’est de l’arnaque: that’s highway robbery!

- se faire arnaquer: to get ripped off, to be had.