If you go to PubMed/MEDLINE, the US National Library of Medicine’s giant repository of (and search engine for) biomedical publications, and look around for papers on language and suicide, you won’t find that much on what you’re probably expecting: research on the language of suicidal people. What you will find is papers on how we talk about suicide.

The major issue has to do with the ways that we refer to the act of suicide. In English, your basic options are:

- to commit suicide

- to kill oneself

- to take one’s own life

- to do oneself in

- to die by one’s own hand

The problem is that first one: to commit suicide. People who work in the field of suicide in any capacity–prevention, treatment, research, whatever–aren’t very fond of it. The reason: it stigmatizes the act. In English, things that you commit are bad.

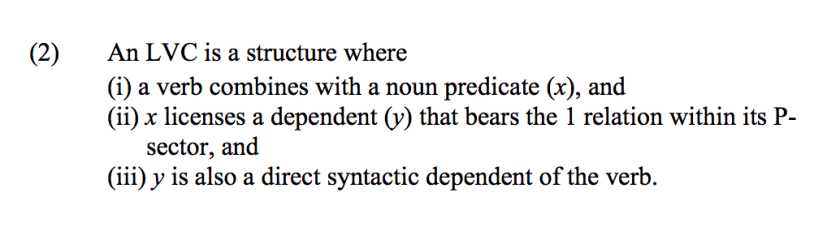

Now, you’re thinking: commit isn’t always bad, right? You can commit to doing something, commit to someone, commit something to memory. No question! But, we’re seeing two very different linguistic phenomena here. The bad commit has a very specific kind of structure: it’s what we call a light verb.

Light verbs are a special kind of verb. They don’t have very much meaning by themselves. Rather, they occur with some other verb, and it’s that verb that gives the expression its meaning. For example: in English, the verb to take can be a light verb. (It isn’t always a light verb–but, there are many times when it is.) Here are some English-language expressions in which to take is a light verb:

- to take a bath

- to take a beating

- to take a break

What does to take mean in to take a bath, to take a beating, and to take a break? I suggest to you that it doesn’t mean very much at all. Rather, it’s bath, beating, and break that contain the meanings of those expressions. (I’ve put a technical definition at the end of the page, if you are into that kinda thing.)

Light verb constructions are not a rare phenomenon. Here are a bunch more expressions in English that are what we call light verb constructions (that means the light verb plus whatever it is that it combines with–in English, typically a noun) in which the light verb is take:

- to take a breather

- to take a bus/taxi/shuttle/plane/train

- to take a dump

- to take a gander (at)

- to take a minute

- to take a pee

- to take a piss

- to take a shit

- to take a vacation

- to take a walk

- to take pity (on)

…and, it’s not like take is the only light verb in English. In fact, we have several. Some examples:

- to make a decision, to make an offer, to make haste, to make peepee

- to give a shit, to give (someone) a hand, to give a damn, to give a fuck, to give birth (plus some obscene ones that I’m leaving out)

- to get dressed, to get ready, to get angry/mad, to get nasty, to get drunk, to get high, to get sober

- to do battle, to do business, to do your business (yes, those are different)

- to have a ball, to have a blast, to have fun, to have a good time, to have a headache, to have mercy, to have sex, to take a piss

- to take action, to take a seat, to take one’s time, to take note, to take notes (yes, those are different), to take a look (at)

With that data in hand, we can see the difference between the commit of to commit suicide and the non-bad senses of commit in to commit to memory, to commit to a person, to commit to a deadline… none of those have that verb + noun structure. They’re all commit + to something.

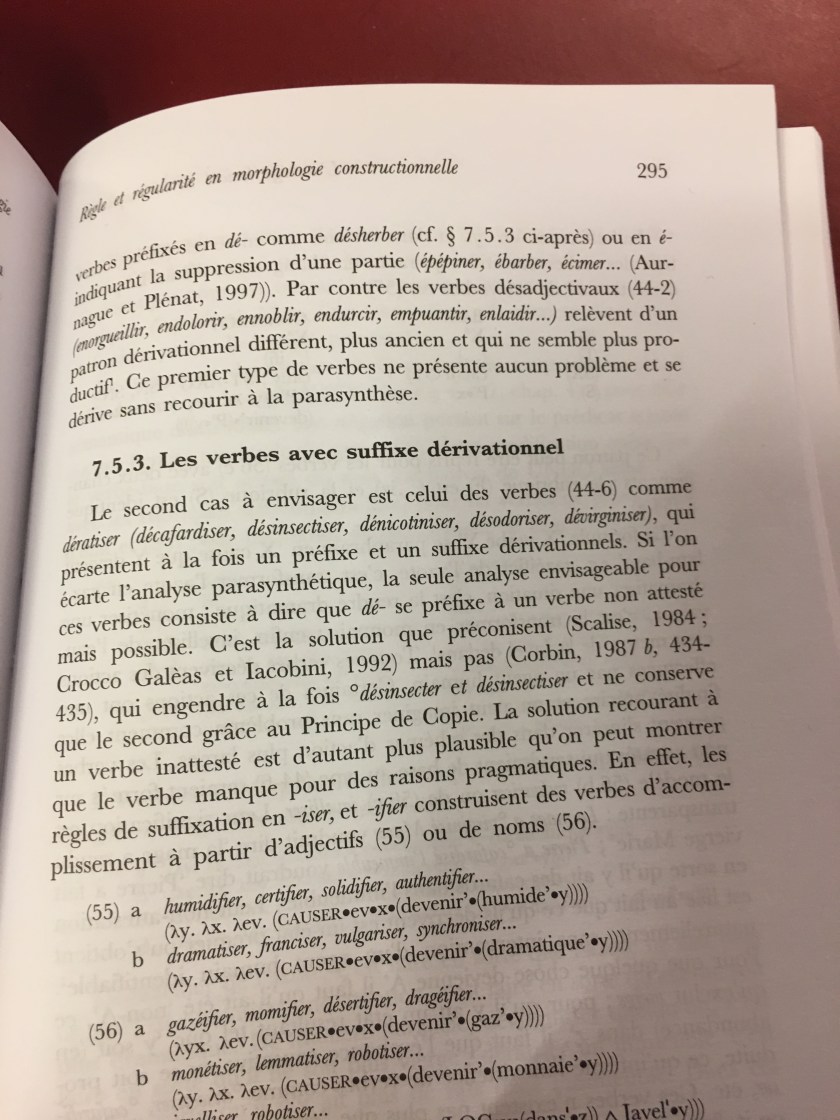

Some more (or less) useful light verb constructions in French: faire la vaisselle: to do the dishes faire la lessive: to do the laundry faire [+université]: to go to a university (J’ai fait William and Mary, I went to William and Mary) faire du [+musical instrument]: to play an instrument (as in to do so habitually) faire du diabète: to have diabetes

One of the interesting things about light verb constructions is that they don’t show a basic characteristic that we expect to see in language: compositionality. To paraphrase from a previous post:

Compositionality is the process of meaning being produced by something that you could think of as similar to addition (technically, it’s a more general “function,” but “addition” will work for our positions–linguists, no hate mail, please). Take a situation where my dog stole some butter. The semantics are: there’s a dog, it’s my dog, there’s some butter, and the butter was taken, by the dog, without permission. (You can’t believe how horrible the poo that I had to pick up over the course of the next 24 hours was.) My dog’s name is Khani, so I might say something like this: Khani stole some butter. The idea behind compositionality is that the meaning of Khani stole the butter is the adding together of the meanings of Khani, steal, butter, and the meaning of being in the subject position versus the object position of an active, transitive sentence.

So: we have this basic expectation that meaning in language will be compositional, and as linguists, as computer science people who work with human language, and as philosophers, we have a hell of a lot riding on that expectation.

In that context, the cool thing about light verb constructions is this: they’re not compositional. There is pretty much no way to get any systematic interpretation of the combinations of light verbs and their nouns. Pause and ponder:

- To make peepee and to take a piss: they mean the same thing (the difference is that one is child language and the other is too impolite to say in front of your grandmother). Peepee and piss mean the same thing–again, one is child language, and the other one is too impolite to say in front of your grandmother. Your assignment: tell me what make and take contribute to the meaning of those expressions–that is, explain to me what their contribution is to the composition of the verb and the noun. My point: peepee and piss mean the same things, and to make peepee and to take a piss mean the same things–how do you explain that, if make and take each contribute something to the meaning of those expressions?

- Consider to take a bath and to take a bus. One of those is what you might think of as event–an act of bathing. The other is a big, smelly thing that takes you to work. (See how I slipped another take in there? Different take–nobody said that linguistics was going to be easy.) In take a bath and take a bus, your relationship with the two things is pretty different. In the first case, you’re participating in an event, while in the second case, you’re making use of a mode of transportation. Your assignment: tell me how that difference comes from the verb to take.

The answers:

- Trick question: as far as I know, make and take don’t contribute anything to the meanings of those expressions. The meanings of the expressions are not compositional.

- Trick question: as far as I know, take doesn’t contribute anything to the meanings of those expressions. The meanings of the expressions are not compositional.

So, back to to commit suicide. As you might have noticed, the relationships between light verbs and their nouns are things that a child learning their native language just has to remember. There’s nothing that the kid learns about their language that would let them infer or guess that they’re making peepee now, but they’ll be taking a piss when they grow up: they have to remember it when they’re exposed to it. (I don’t mean to suggest here that children learn language by remembering stuff to which they’ve been exposed–we’ve talked about how very little of language-learning for children works that way.)

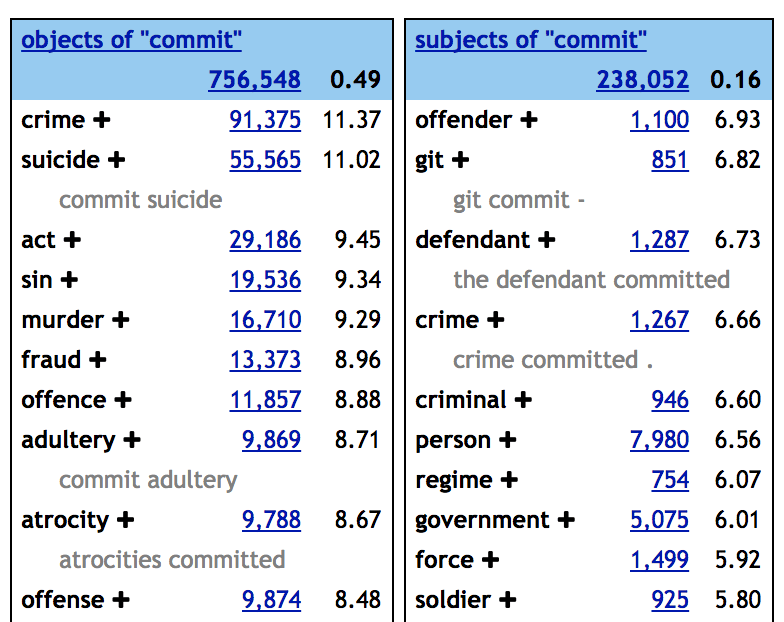

So, the verb + noun combinations in light verb constructions are pretty random. The thing about commit is this: it’s a light verb, too, in constructions like to commit suicide. Its noun is of a very specific kind, though: its verb is something bad. Compare that with the light verb to have. You can have a heart attack, you can have a migraine, or you can have a good time, or have sex. No particular semantic consistency there–could be bad (heart attack, migraine), or it could be good (a good time, sex). Here’s a list of the words that are statistically most closely associated with the verb to commit in the enTenTen corpus (a collection of 19.7 billion words of written English, available on the Search Engine web site; git is a computer science thing. See this post.)

What kinds of things get commited? Crime, sin, murder, fraud, atrocity. Who commits things? Offender, defendant, criminal. Not good.

So, what are we to make of to commit suicide? Many people who work in the field (go do your own search on PubMed/MEDLINE if you’re interested, or just see here and here for examples) are of the opinion that use of the expression to commit suicide has the effect of stigmatizing the person who killed themself. Is that a bad thing? They think it is. I think it is, too. Now, does the person who killed themself care how you talk about them? Certainly not–they’re dead. But, that person’s mother, husband, son, daughter, cousin, aunt, uncle, best friend… They do, and they’re not dead. So, many people who work with suicide in some capacity would like to see that expression go away. Here’s a very eloquent expression of the idea, from Doris Sommer-Rotenberg:

The expression “to commit suicide” is morally imprecise. Its connotation of illegality and dishonour intensifies the stigma attached to the one who has died as well as to those who have been traumatized by this loss. It does nothing to convey the fact that suicide is the tragic outcome of severe depressive illness and thus, like any other affliction of the body or mind, has in itself no moral weight. —Doris Sommer-Rotenberg, Suicide and language

Who cares? Sommer-Rotenberg again:

The rejection of the term “commit suicide” will help to replace silence and shame with discussion, interaction, insight and, ultimately, successful preventive research.

Now, I know what you’re thinking: you’re thinking that the language that we use doesn’t affect the way that we think. You know what? I agree with you. However: even if how we talk about suicide doesn’t change the way that we think about it, I suggest to you–as a fellow student said to me in the basement of Oxley Hall one evening in our graduate student days: the fact that the language that we use doesn’t change our reality doesn’t change the fact that you can make someone feel bad with the language that you use, and you wouldn’t want to do that, right? Well, of course not. (I love my job, but my fellow ex-student’s job is definitely cooler–she’s the only speech therapist in New York City whose practice is exclusively concerned with transgendered people.)

There’s also controversy/discussion around the ways that we talk about what happens when people try to kill themselves, but don’t succeed–attempted suicide, unsuccessful attempt, failed attempt, failed suicide, and failed completion, versus completed suicide–the idea is that these expressions model suicide as a desirable act. (If you fail to have a good time, fail to get into medical school, fail to convince someone to marry you, that’s a bad thing.) See here for a fuller discussion.

So, yeah: there’s probably more stuff in the National Library of Medicine’s repository on how we talk about suicide than there is on how people who are suicidal talk. It would be great to change that, because if we knew more about how people who are suicidal use language, then we might be able to do a better job of preventing it. Now, that means that we need language data from people who are or have been suicidal, right? But, we also need data from people who aren’t suicidal–if you want to understand something, you usually need to compare it to something else, and in this case, that means comparing the language of suicidal people to the language of people who aren’t suicidal.

It happens that there’s an enormous amount of real, live language out there in the world on social media platforms. It would be great for suicide researchers to have it, but there are ethical issues involved–just because someone puts their life out there on the web doesn’t give you the right to just grab it and do stuff with it. However: you can donate your social media data to OurDataHelps.org, a group that collects language from all kinds of people for social media research. You can sign up with them here. As the character Père LeFève says in Anne Marsella’s wonderful short story The Mission San Martin:

Best wishes to all of you who are still alive. And if you’re yet alive, please give.

–Anne Marsella, The lost and found and other stories

No English notes as such today. Instead, here’s some extra stuff for those of you who like to dive deeply into the linguistics of things.

One way of defining light verb construction:

On the mechanics of how the meaning gets out of the noun and into the verb, so to speak:

Contrary to “prototypical” verbal constructions where the verb is the syntactic and semantic head of the sentence and its syntactic dependents are also its semantic arguments, in LVCs, one of the syntactic dependents of the verb, generally its direct object, functions as the semantic head, projecting its own argument structure, while the verb, which is semantically “light”, bears only inflection and projects no argument structure.

− Given the fact that the verb has no semantic contribution or rather its semantic contribution is quite weak, it cannot be selected lexically, that is on the basis of its semantic contribution. The combination of a particular predicative noun (PN) with a particular light verb (LV) is thus a matter of idiosyncrasy: The noun and the verb form a collocation that must be stored in the lexicon.

Pollet SAMVELIAN, Laurence DANLOS, and Benoît SAGOT, On the predictability of light verbs

Why would you need to posit the existence of such a thing? From Samvelian et al.:

- l’agression de Luc contre Marie (the attack of Luc against Mary)

- Luc a agressé Marie (Luc attacked Mary)

- Luc a commis une agression contre Marie (Luc committed an attack against Mary)

- l’agression que Luc a commise contre Marie (the attack Luc committed on Mary)

Note: you can also se commettre avec quelqu’un.

English notes

English notes