One evening I was riding the metro home when a guy got into the car with some used books to sell. A man sitting across the aisle from me asked to see them. He flipped through one of them, then took a pen out of his jacket pocket and began circling words–in this book that the other guy was trying to sell. Are you going to buy that?, the would-be bookseller asked the guy with the pen. They exchanged words–the bookseller was not happy about having his books marked up. The bookseller said something that Mr. Pen apparently thought was obvious or stupid. Il est fort, lui, he snorted–he’s a sharp one.

The central meaning of fort/forte is “strong,” but it can also be used adverbially. You hear it a lot that way, and I’ve been trying to figure out exactly when you can use it in that way–it’s often the case that there are word combinations that are possible in a language, but that don’t sound right. Rather, there are particular words that are conventionally used in very specific combinations. Violeta Seretan of the University of Geneva gives some examples of English words that are used to describe the magnitude of various nouns. The semantics of each of these is the same, but the words that are typically used are quite different. We talk about big problems, heavy rain… How about injury? (Answer below.) It would certainly be possible to say large problem, but it’s nowhere near as likely, and it sounds odd, as a native speaker. For example, you could say large problem, but it seems odd. I wanted to be able to demonstrate that this corresponds to some actual statistical tendency, not just my intuitions, so I searched the enTenTen corpus, a collection of almost 20 billion words of written English, looking for big problem and large problem. Here are the frequencies:

- big problem: occurs 6 times per million words.

- large problem: occurs 0.5 times per million words.

Big problem occurs twelve times more often than large problem–the latter is possible, but it’s not really what you would expect to hear from a native speaker. We call these things like big problem “collocations”–combinations of words that occur statistically more often than you would expect by chance.

You can find collocation dictionaries for English, and they’re quite useful for second-language learners. I don’t know of any for French, though, or at least not where to find them in the US, which is where I am at the moment. (I’ve seen similar things in Canada.) I additionally want to know how these adverbial uses of fort should be translated into English, so I need a way to figure this kind of thing out for myself.

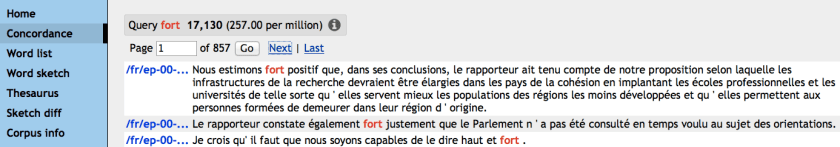

First step: find a whole lot of French text in some easily searchable form. I started with the French section of EUROPARL–a collection of documents from the European Parliament, translated to/from a wide variety of languages. The French section of EUROPARL contains about 59 million words–so, a whole lot–and you can access it through the Sketch Engine web site–so, easily searchable. A quick search showed me that fort is quite common in that data set:

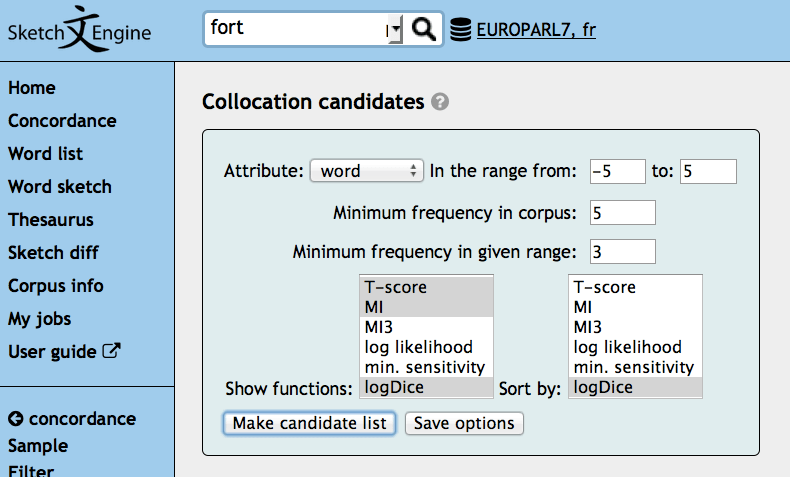

Once I know that, I know that there will be enough data to calculate the collocations–recall that this is a statistical thing, so you need plenty of data. The Sketch Engine interface gives me a number of options for how to do the calculations (scroll down to get past the screen shot):

…which I show you just so that you’ll see that there are a lot of approaches to doing this. I just went with the defaults.

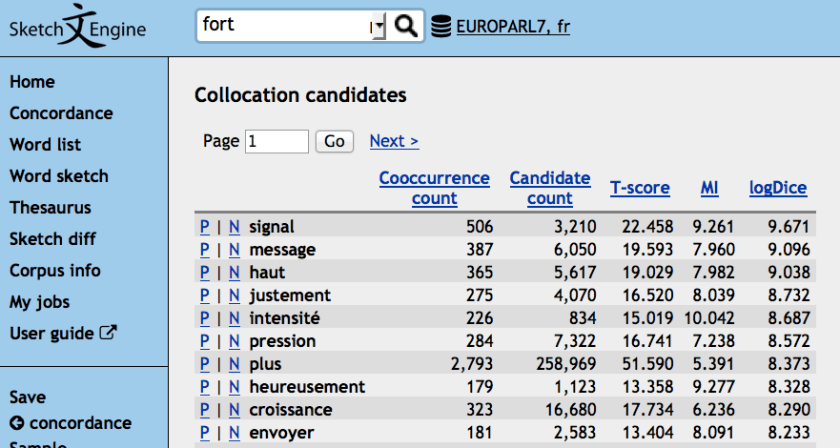

The calculations yielded quite a few possibilities. Here are some of them:

If you’re a stickler for data, you might have noticed that the collocations are ordered by the log of the Dice coefficient, which you could think of as a measure of the statistical effect, I guess. I am really looking for the most common collocations involving fort, though, so I’ll reorder by the cooccurrence count, i.e. the raw count of how often the collocations occurred:

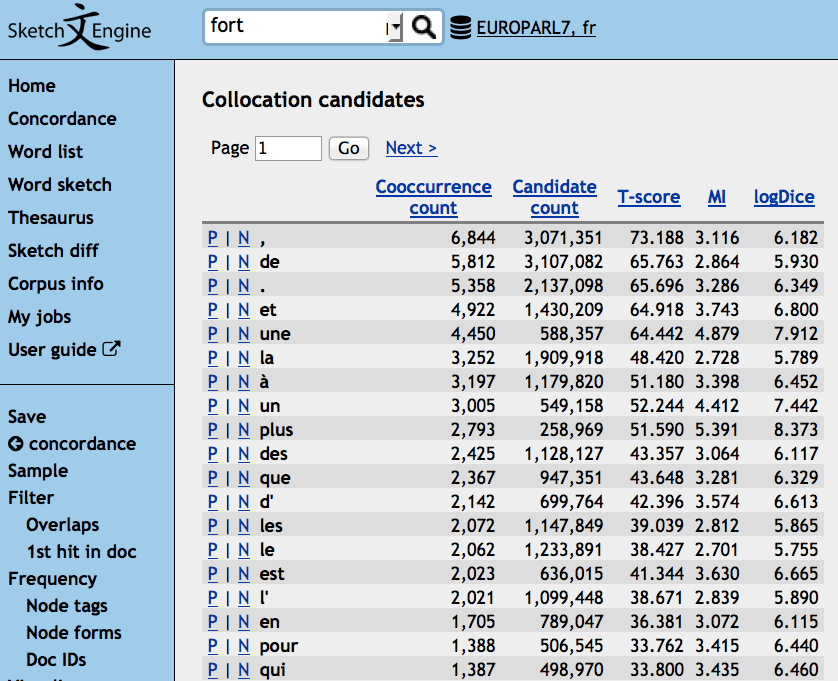

Crap–that basically tells me nothing. Why not? Zipf’s Law. Remember that Zipf’s Law tells us not only that most words are pretty rare, but also that some words are really, really common, and in French, that certainly includes de (“of”), et (“and”), une (“a”), and the rest of what we’re seeing here. (Moral of the story: don’t expect the most frequent things in a language to necessarily be the most revealing things in a language.) If I scroll down a bit, though, I see bien on the list. 683 examples of this–a frequency of 10.25 per million words. Bien is often an adjective, which would presumably make fort adverbial in these cases, so we’re on to something now. Let’s check out some of those examples:

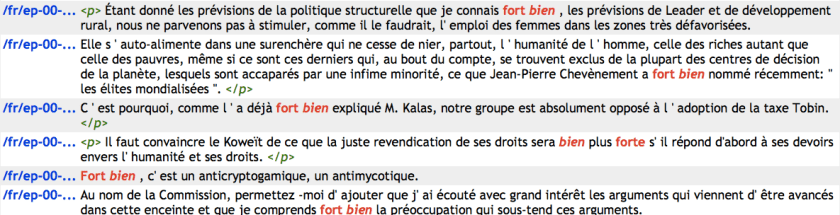

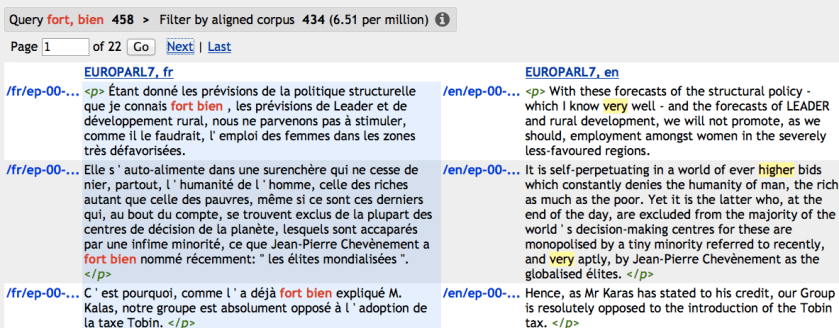

So, now I have some cases where it would make sense to use fort, but I want to know how they would correspond to English, too. This requires that I have access to the corresponding English text. No problem–recall that the EUROPARL corpus is multilingual. In particular, it is what is known as a parallel corpus, which means that it contains the same contents in multiple languages, not just similar contents (although that kind of corpus can be useful, too). I searched for the phrase fort bien. Here’s an example of the output:

So, now I have some French/English equivalents for fort bien:

- Étant donné les prévisions de la politique structurelle que je connais fort bien … With these forecasts of the structural policy – which I know very well…

- …ce que Jean-Pierre Chevènement a fort bien nommé récemment… …referred to recently, and very aptly, by Jean-Pierre Chevènement…

- C’est pourquoi, comme l’a déjà fort bien expliqué M. Kalas… Hence, as Mr Karas has stated to his credit…

- …je comprends fort bien la préoccupation… … I have a great deal of sympathy for the unease…

- Vous savez fort bien que… You know very well that…

- …non seulement parce que le président le connaît fort bien… …not only because the President is very familiar with it…

- Il est fort bien d’ organiser des réunions, mais ce sont les résultats qui comptent. Meetings are all very well, but it is the result that counts.

- …ils se tirent fort bien d’affaire. …they are managing really rather well.

- …et je les comprends fort bien. …which I fully understand.

- Ils les connaissent fort bien et un par un. They recognise each and every one of them very well.

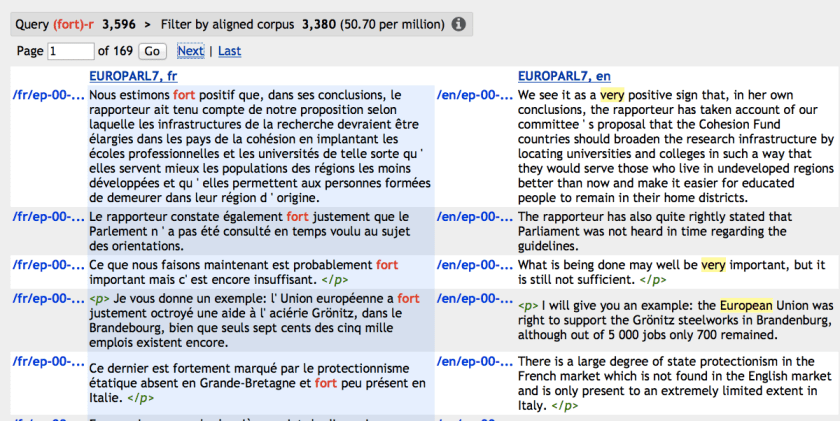

I’m feeling good about how to use fort bien now, but I want to know about other ways that fort could be used with an adjective. So, I’ll do another search of the parallel corpus (i.e. the matched French and English texts), but this time I’ll just search for fort, and I’ll specify that I want it to be an adverb. Here are some of the results:

Now I have some general examples of how to use fort:

- Nous estimons fort positif que… We see it as a very positive sign that…

- Le rapporteur constate également fort justement que… The rapporteur has also quite rightly stated that…

- Ce que nous faisons maintenant est probablement fort important… What is being done may well be very important…

- …l’ Union européenne a fort justement octroyé… …the European Union was right to support…

- …nous entretenons des relations bilatérales fort satisfaisantes avec… …We have very satisfactory bilateral relations with…

I don’t know every adjective with which it would be OK to use fort, but I know one more than I did when I got out of bed this morning, and I’m cool with that–one less time when I’ll have to use très, which is all that they teach us in school.

A colleague had some observations on this:

On top of being used in collocations, it also marks a style / genre which is somewhat formal or elevated (“soutenu”). This might explain why it remains frequent mostly in collocations and is less frequent (or more marked) in freer combinations. This gives the expression a literary turn or a pretense to a higher register. Both in speech and in writing, it is “soutenu.”

Another native speaker had this to say about it:

“Fort” is used as a synonym of “très”, before adjectives or adverbs . You can use it in about any case, it’s just more elegant than “très”, but not really literary .

The Mr. Pen guy on the subway turned out to be pretty crazy, as far as I could tell. At one point he snapped at my adorable cousin, who happened to be visiting, and I told him to cut it out. This was followed by an initially amusing conversation between him and me that at some point degenerated into a loud tirade on his part. I kept telling him that my French wasn’t that good and I couldn’t understand him, but he just kept going and going. Eventually French people around us began telling him to stop being an asshole and words to that effect, so I assume that it wasn’t very nice, but honestly, I couldn’t tell you. At some point a large and very drunk French guy got on the subway car, and started seriously getting in Mr. Pen’s face–it was clear that this was going to turn violent. Mr. Pen was a very diminutive Haitian man, and I wasn’t going to watch him get the shit beaten out of himself no matter how bizarre he was being, so I got involved. The train stopped, Mr. Pen jumped out, and Mr. Drunk Guy launched into an animated discussion with me about American heavy metal, punctuated by snatches of Metallica songs. All in all, an unusual evening on the metro, but not an unpleasant one by any means–just part of life in The Big City, as we say in English.

Oh: it’s serious injury.