Until the 1960s or so, there were basically two ways to do linguistic research.

- If you were into historical linguistics and/or dead languages, you looked at ancient texts.

- If you were into living languages, you went and camped out on a reservation, in a village, or whatever, and you sat with native speakers and your notebook and you collected data. You transcribed things, and then went home and copied out your notes, and then you thought about them a lot.

In either case, the underlying philosophy was that there was some body of data in your hands, and your task as a linguist was to come up with a description/explanation of what was in that body of data. Seems straightforward enough.

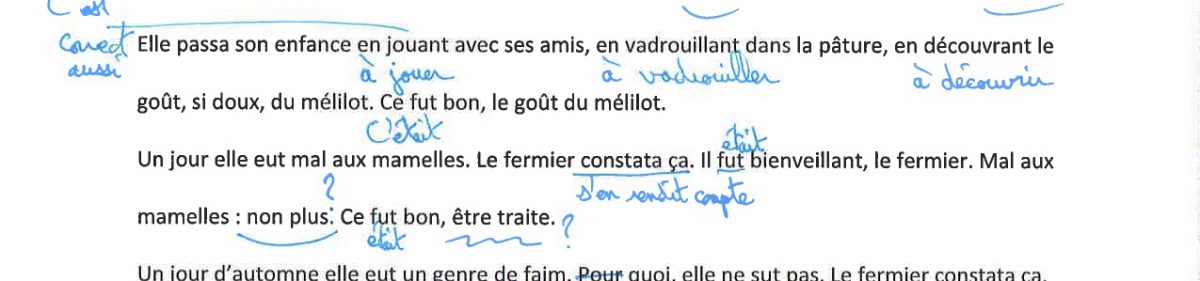

In the 1960s or so, the American linguist Noam Chomsky turned the world of linguistics upside down with the idea that what you should be doing is describing/explaining native speakers’ intuitions about their language. Intuition is a technical term here–it refers not to “what Kevin happens to think is the case about his native language,” but to native speaker judgements about questions like Is the sentence “I saw the man on the hill with a telescope” ambiguous? This changed the conception of what constitutes “data” enormously. On this view of linguistics, there’s no need to go freeze on the Siberian tundra to get your data–you can do it in your living room. Les données, c’est moi !

Today linguists are less likely to talk about binary “yes it is/no it isn’t” questions than they are about gradient judgments–“Sentence X is more acceptable than sentence Y”. For a really good discussion about the issues from a perspective I think you’ll like, see the work of John Sprouse under the general heading of “experimental syntax.”

–Philip Resnik

From a philosophical perspective, this was a radical shift–from empiricism (sometimes a very extreme empiricism, as for example in the case of Leonard Bloomfield (leading American linguist of the first half of the 20th century, author of the first article published in the journal Language, and Yale professor who was refused membership in the Faculty Club because they didn’t let Jews join in those days), who was of the opinion that mental states are not observable, and therefore semantics is not a fit topic for science) to rationalism, and a rather extreme rationalism at that. Not everyone was happy about this, and in fact most older linguists weren’t–from a methodological point of view, it’s hard to see how you could falsify a hypothesis when the evidence that’s being presented is some version of yes it IS ambiguous–but Chomsky took the grad students by storm, and linguistics underwent a radical change. It swept the world of academia in a way that it never had before, too. (Check out Randy Allen Harris’s The linguistics wars for details.)

Meanwhile, Henry Kučera and W. Nelson Francis were thinking about the potential for computerized analysis of language, and in 1967 they published Computational Analysis of Present-Day American English, based on the study of a bit over one million words of American English that they had had typed up by keypunch operators. They were at Brown, and called their data set, which they made available to the public–now you could check someone else’s data–as the Brown Corpus. As far as I’m aware, that data itself didn’t lead to any earthshaking discoveries, but it did make people’s ears perk up: it was clear that there were possibilities for doing defensible studies of language when you could search a large body of text with a few keystrokes that just weren’t there if your data were whatever you happened to need to intuit that morning. Or whatever your grad student happened to need to intuit that morning. Or, in a pinch, whatever you happened to need to intuit in the heat of your dissertation defense.

There were some issues with the Brown Corpus, or at any rate, with trying to make similar corpora (the plural of corpus) on your own. One was copyrights. The Brown Corpus was what is called a stratified sample: it deliberately tried to structure its contents. Those contents included fiction, non-fiction, personal correspondence, books, newspaper articles–all sorts of stuff, much of which required getting permission from someone or other. Then there was the matter of those keypunch machines–all 1,014,312 words had to be entered by hand. People continued to pursue the construction of corpora, and cool things came out of that work, both in terms of linguistic theory and in terms of designing computer programs that could do things with language. But, it was slow going–people realized that bigger and bigger corpora would let them do cooler and cooler things, but typing is neither fast, nor inexpensive.

Then a miracle happened: the Internet. All of a sudden random people around the world were vomiting forth massive quantities of linguistic data, and it was mostly copyright-free, and they were typing that shit themselves. Nectar! Now you can get access to billions of words of text in an amazing variety of language. Is it necessarily clean, pretty, or legible? No. Is it real? Yes, and that’s what matters, at least to linguists. My colleague Graciela Gonzalez at Penn has done amazing things with social media data, ranging from monitoring medications for previously unknown adverse effects to monitoring prescription medication abuse.

Until recently, there was remarkably little data available on the language of suicidal people, or even on the language of people with psychiatric disorders in general. This is surprising, because with so many mental illnesses, the symptoms are, for the most part, expressed via language. As Philip Resnik, Rebecca Resnik, and Margaret Mitchell put it in the introduction to the proceedings of the first Association for Computational Linguistics workshop on computational linguistics and clinical psychology in 2014,

For clinical psychologists, language plays a central role in diagnosis. Indeed, many clinical instruments fundamentally rely on what is, in effect, manual annotation of patient language. Applying language technology in this domain, e.g. in language-based assessment, could potentially have an enormous impact, because many individuals are motivated to underreport psychiatric symptoms (consider active duty soldiers, for example) or lack the self-awareness to report accurately (consider individuals involved in substance abuse who do not recognize their own addiction), and because many people — e.g. those without adequate insurance or in rural areas — cannot even obtain access to a clinician who is qualified to perform a psychological evaluation.

Suppose you’re interested in the language of suicidal people. Until recently, if you wanted to get your hands on actual data, you could get your hands on a set of suicide notes collected and annotated by my colleague John Pestian at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center (and me and a bunch of other people). That data has been revealing, and we’ve learnt things about suicide from that data that we didn’t know. But, that data was hard to come by. Putting that data set together took years (if you can read French, you can find a paper here on some of the issues), and if you want to get your hands on it, you need to go through some hoops to demonstrate that you have a legitimate research interest, that you will not be posting people’s suicide notes on Facebook or Pinterest, and so on.

Social media has changed all of that. In fact, the past couple years have seen an explosion of work on the linguistic characteristics of mental states associated with mental illness, including suicidality. Much of it has appeared in the proceedings of CLPsych, the above-mentioned Association for Computational Linguistics workshop. To give you some examples:

- Glen Coppersmith and his colleagues at Johns Hopkins worked with tweets from people with post-traumatic stress disorder, seasonal affective disorder, depression, bipolar disorder, and psychiatricaly healthy controls. They found that based on the contents of the tweets, they could do a pretty good job of classifying which of those categories the poster belonged to. They tried various methods of representing the contents of the tweets, and found that they got the best results with what are called statistical language models. In a later paper, they looked at six more conditions, and added exploratory analysis on the distributional characteristics of emotionally relevant language.

- Margaret Mitchell of Microsoft and her colleagues worked with tweets from schizophrenics and healthy controls, and found some unexpected signals in the language of the schizophrenics. For example, the schizophrenic social media users were statistically more likely to use what linguists call hedging expressions like think, I believe, or I guess.

- In one of my favorite papers of this ilk, Munmun De Choudhury and their colleagues looked at the language of people who moved from a Reddit for people with mental health related diagnoses to a suicide watch Reddit. They found a number of differences in the language of those Reddit users who moved to the suicide watch group and those who didn’t, including differences in what is called accommodation: the ways that we (can) adjust our language to that of the people with whom we’re communicating. (A post on the subject is in the works.)

Now, there’s an issue here: just because people post their lives on social media doesn’t mean that it’s OK for you to use that stuff for your own purposes. Ethical questions abound, and that’s just as true for the tweets, posts, or whatever of the psychiatrically healthy controls as it is for those with mental illness, suicidal behavior, or whatever. And that’s where you come in.

OurDataHelps.org is a group that collects social media data, particularly linguistic data, for use in doing research like the stuff that I’ve described here with the goal of suicide prevention. They want your data if you have ever flirted with suicide, but they want your data if you haven’t, too–you always need something to compare to, and people like me need data from non-suicidal people to compare to the data from suicidal people. That could be you! Check it out: OurDataHelps.org.

Work in this space is definitely emotionally taxing. I find myself with a rule similar to John’s “no more than 10 a day” rule — enough to constantly remind me of the importance of this work, without becoming emotionally oppressive. The emotional response to spot-checking the data is qualitatively different and far more visceral than something like sentiment analysis of beer reviews.

–Glen Coppersmith

One day I needed to read through some suicide notes. I set an afternoon aside to do it. I made it through about 150–an hour, maybe–before I read one that was like being punched in the stomach. I went out and bought a pack of cigarettes, and I didn’t even smoke (at the time!). I spent a lot of time over the course of the next couple weeks trying to forget it. I mentioned it to John. All afternoon? Man, you can’t do that–10 a day, max. He was, of course, right. In this kind of work, ethical issues come up with the researchers, too. We now provide free therapy for the people who transcribe data for us on suicide-related projects, our researchers who work directly with the data are required to visit a therapist or a clergyman once a month, and we rotate research assistants off of the project every quarter. Moral of the story: I don’t recommend that you go digging around in this data out of curiosity. But, you can be the data–suicidal or not, why not donate your social media data to OurDataHelps.org and maybe keep someone else from writing one of those notes?

Thanks to John Pestian, Philip Resnik, and Glen Coppersmith for their comments and contributions. French notes follow.

French notes

le suicide: suicide

le/la suicidé(e): person who kills themself

suicider: to drive someone to suicide; to make someone’s death look like suicide

se suicider: to kill yourself

se donner la mort: to kill yourself

la tentative de suicide: suicide attempt

maquiller un meurtre en suicide: to make a murder look like a suicide

l’attentat-suicide: suicide attack

la mission suicide: suicide mission

la lettre d’adieu: suicide note

English notes

English notes