A very good thing about France: the French don’t really do protest votes. That’s not to say that we don’t have the ni-nis—those who say that they won’t vote ni for Macron, ni for Le Pen. A ni-ni might abstain, or voter blanc–-submit a blank ballot. But, it’s not exactly a common thing in France. France has a two-round election process, with multiple candidates in the first round, and only the top two finishers in the second (except in the unlikely event where someone takes more than 50% in the first round.) People sometimes say that you vote the first round with your heart, and the second round with your head.

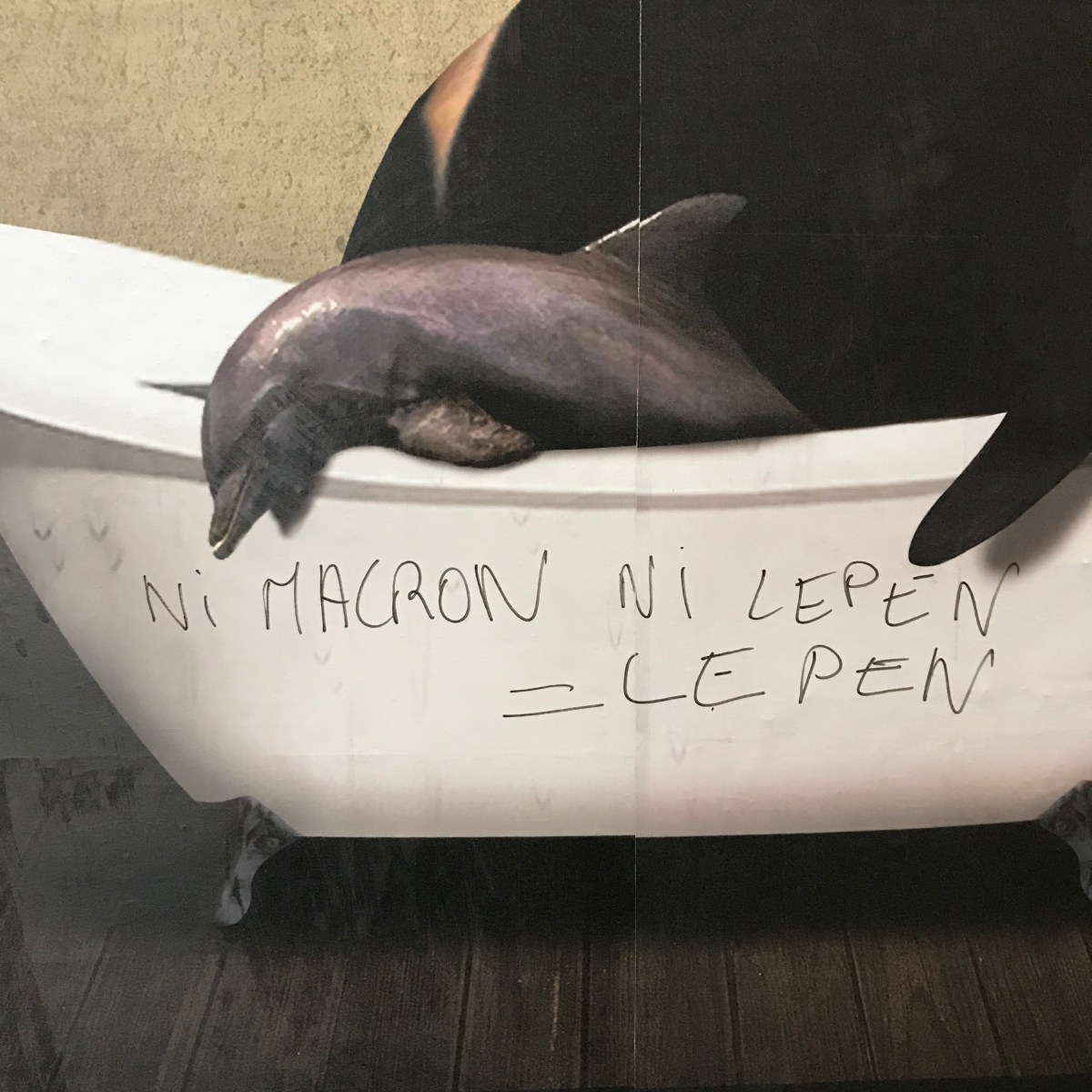

I would say that Americans vote 80% on emotion, and 20% on the basis of their takes on the candidates’ actual policies. (I don’t except myself from that; “one’s take on something” explained in the English notes below.) In contrast, I would guess that the French tend to vote 20% on emotion, and 80% on the basis of their takes on the candidates’ actual policies. I know plenty of people who aren’t at all crazy about Macron’s proposals for the economy, but given a choice between someone about whom they’re not crazy and some Nazi sociopath, of course they’re going to vote for the guy about whom they’re not crazy. The photo above–some graffiti that I saw as I walked into a metro station this morning–is representative of the opinion of everyone with whom I’ve talked: deciding not to vote for either of them is to vote for Le Pen.

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.–W. B. Yeats, The Second Coming, 1919

The worry of most of the people I know is that Macron is so far ahead of Le Pen in the polls that everyone will assume that he’s going to win, and too many people will decide that they don’t need to vote, and then the Le Pen voters all show up, and boum–Le Pen wins.

I was never really all that struck by Yeats’ poem The Second Coming when I was an English major in college. We mostly contented ourselves with showing off our knowledge of what a gyre is, and moved on to Beowulf, or Salman Rushdie. But, ever since Obama got elected and the Republican Party went insane over the sight of a black man in the Oval Office, The Second Coming has become more and more meaningful to me. With Trump in office, it has gone past “meaningful” towards “frightening”–at the very least, foreboding.

The polls in France close in four hours. We’ll see what happens.

The Second Coming

W. B. Yeats, 1919

Turning and turning in the widening gyre

The falcon cannot hear the falconer;

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

Surely some revelation is at hand;

Surely the Second Coming is at hand.

The Second Coming! Hardly are those words out

When a vast image out of Spiritus Mundi

Troubles my sight: somewhere in sands of the desert

A shape with lion body and the head of a man,

A gaze blank and pitiless as the sun,

Is moving its slow thighs, while all about it

Reel shadows of the indignant desert birds.

The darkness drops again; but now I know

That twenty centuries of stony sleep

Were vexed to nightmare by a rocking cradle,

And what rough beast, its hour come round at last,

Slouches towards Bethlehem to be born?

English notes

One’s “take on” something is your opinion, or analysis of, it. Note that this is entirely different from the verbal idiom to take something/someone on.

- I want to comment on Trump’s take on the Civil War and Andrew Jackson… but, seriously, it hurts me. READ A BOOK! (Twitter) (Context: Trump recently said something about a former populist president, Andrew Jackson, that is consistent with either (a) Trump being an uneducated idiot who, in particular, doesn’t know anything about American history, or (b) Trump being a very bad person.)

- Gr8, some sources just hav a screwed up set of priorities. Who cares about Trump’s take on med marijuana when the health care plan sucks?! (Twitter) (Context: the Republican-controlled House of Representatives just voted to repeal Obamacare and replace it with a disaster.)

- Trump’s take on Andrew Jackson isn’t astonishing; what is astonishing is that this country elected an ignorant pussy-grabbing Richie Rich. (Twitter)

- My take on Trump is that he just wants to be liked by whoever is in front of him, which makes him inconsistent and unreliable. (Twitter)

- My take on Trump’s worse-than-worthless briefing to every senator on the North Korean problem. (Twitter) (Context: here’s a link to the Tweeter’s article on Trump’s attempt to swing the Senate in his favor with respect to whatever crap he’s brewing concerning North Korea.)

How I used it in the post: I would say that Americans vote 80% on emotion, and 20% on the basis of their takes on the candidates’ actual policies.