5:01 AM Wake up. Check phone to see if Trump launched a missile strike last night because a teenager made a web site where you can watch a kitten scratch his face and his feelings were hurt. (Remember how he used to say that Hillary isn’t “tough enough?”) Lie in bed for half an hour listening to the news and trying to get back to sleep.

5:30 AM Get up. To the balcony with coffee and a cigarette. Wonder if the drunk guy staggering down the street is “your” drunk. (Fascinating guy–gave me a long lecture the other day on the differences between Western European and Eastern European Roma, with statistics.) Make sure you have passport & French visa.

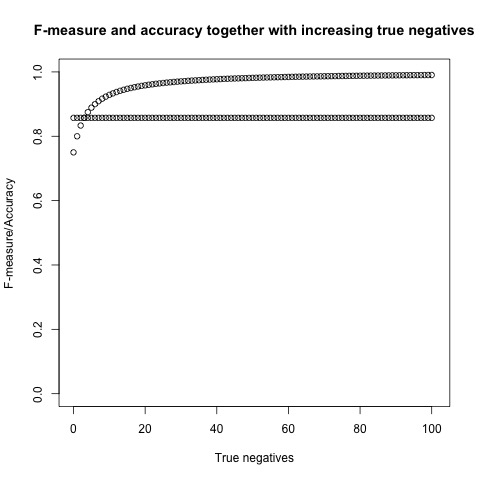

5:39 AM Check email. Find a web site that lets you tinker with minor changes to variables and watch the level of statistical significance go up and down.

6:00 AM Alarm goes off. Be happy that you’re half an hour ahead of schedule.

6:20 AM Realize that you have a plane to catch and you’ve just spent 40 minutes tinkering with minor changes to variables and watching your level of statistical significance go up and down. Into the shower. (Sous the shower, in French–I still struggle with this.)

6:30 AM Start downloading TV shows onto your phone.

7:06 AM Realize that you have a plane to catch, and you’ve just spent 36 minutes downloading TV shows onto your phone. Charge spare battery while you empty the refrigerator.

7:10 AM Take pre-flight aspirin and drink pre-flight glass of water–blood clots suck. Pack daily medications. Pack emergency medications. Pack the extra emergency medications that you need when you fly, because you just can’t take 15 hours on airplanes like you used to. Sucks getting old…

7:30 AM Update Gmail Offline. Check to see if Trump has launched a missile strike to distract from yet another revelation about members of his campaign being unregistered agents of foreign government, and a hostile one, at that. (Remember when he always called her “Crooked Hillary?”)

7:31 AM American keys: check. American dollars: check. American driver’s license: haven’t seen it in months. Whatever. Make sure you have passport and French visa.

7:35 AM Make sure you have your passport. Pack paper to edit on the plane: semantic relations in compound nouns. Download another TV show.

7:40 AM Pack gifts: poster of a skeleton playing a banjo that you bought from a bouquiniste for your father. Camembert box and a snail tray for your mother. Mustard for an ex. Remember to pick up macarons and salted butter caramel at the airport. Pack another paper to edit on the plane: inter-annotator agreement and linguistic data.

7:45 AM Stick the clothes that you pre-packed last night into your suitcase: only two days’ worth, ’cause this is a passage éclair, plus you have spare clothes pre-positioned in Denver–must pre-position stuff when you live out of your suitcase.

7:49 AM Wonder why you have 18 euros in 2-euro coins in your pants pocket.

7:53 AM Empty ashtrays. Check news again to see if Trump has launched a missile strike because he’s pissed that he can’t violate the Constitution by discriminating against people because of their religion. Empty trash. Make sure you have your passport. Second pre-flight glass of water–blood clots suck.

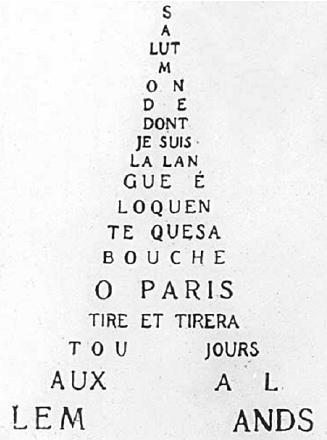

8:00 AM Out to the balcony for a cigarette. Think a lot about how well the woman who’s walking down the street’s shoes match her dress. Advantage of having a boyfriend who’s descended from a long line of women’s clothing retailers: I will notice what you’re wearing, and if you ask me what I think about it, I’ll give you my honest opinion. Disadvantage of having a boyfriend who’s descended from a long line of women’s clothing retailers: I will notice what you’re wearing, and if you ask me what I think about it, I’ll give you my honest opinion. Get into a discussion on the phone of how to say “awakeness” in French.

8:33 AM Realize that you’ve just spent 33 minutes having a discussion on the phone of how to say “awakeness” in French–and you have a flight to catch. Hang up and shave–I look disreputable enough as it is, and getting on a plane unshaven just isn’t a good idea if something should happen to go wrong with my ticket/seat assignment/United club membership/whatever.

8:55 AM Pre-flight back stretches. Sucks getting old…

9:20 AM Time to head to the airport. Realize on your way out the door that you almost left your iPhone headphone adapter on the kitchen table, without which your 15-hour trip to the US would be hell since Apple’s stupid iPhone 7 redesign. First World Problem, I know–but, still: flying without the ability to listen to podcasts is miserable. Make sure you have your passport. Carry your luggage down the stairs. The big suitcase first, before your legs are exhausted. Suitcase in your left hand even though that’s the side of your back that hurts, so that you can hold on to the railing on the tight, tight, tight circular staircase of your poor-man’s-Hausmannian apartment building.

9:24 AM Look for a taxi cab, because you see the taxi cab drivers’ point of view in the whole Uber issue. As usual, there’s no taxi, so duck into a side street and call Uber. While you’re waiting, look up at your apartment and hope that the zombie apocalypse doesn’t start while you’re gone, because Paris is definitely going to be a better place to survive the zombie apocalypse than where you’re going.

Now, I know what you’re thinking: what kind of sick bastard spends 40 minutes on a web site that lets you tinker with minor changes to variables and watch the level of statistical significance go up and down? Well: you should spend a little while watching statistical significance levels go up and down as you make minor tweaks in variables. Ever hear someone claim about how they’ve given up trying to follow the news about health or science because it seems like what’s good for you one day is bad for you the next, and then good for you again the next, and eventually they just give up and stop listening to the science and health news? Well, in fact it’s not the case that caffeine, or meditation, or oatmeal was good for you one day, and then it wasn’t the next. Rather, some thing can be true in one set of conditions but not in another. Even given the exact same data, the way that you frame the research question and do the analysis can have crucial effects on the statistics of the results. It’s not like people are running around deliberately manipulating their data or their analysis–often, it just isn’t clear what the relevant conditions are for your experiment, or how exactly you should be framing the research question, or how exactly you should be doing the analysis. Take 5 minutes to go play with this web site, where you’ll find data on the US economy going back to 1948, and a bunch of options for analyzing it. Then we’ll talk about the difference between the paper that the economist writes about this data, and how an economics journalist will talk about those research findings in the newspaper.

You’re back? Great. Let’s talk about what you saw.

You were working with the same data the entire time–the facts never changed. What you changed by making different selections was the way that you framed the question and did the analysis. This is hidden to some extent by the way that the web site explicitly frames the question: Is the US economy affected by whether Republicans or Democrats are in office?

- You’re going to have to frame that by looking at the economic numbers with either Republicans in office, or with Democrats in office. When I picked Republicans to be the party on which I did my statistics, the Presidency as the definition of “being in office,” employment as my index of the performance of the economy, and I excluded recessions, then guess what? When Republicans are in office, the economy is affected, and in a bad way. But, guess what? If I include recessions, then the answer to the question Is the US economy affected by whether Republicans or Democrats are in office? is “no.”

- Oh–what was all of that stuff about what you use as your index of performance of the economy? It turns out that how you measure “performance of the economy” has a big effect on the statistics. If you define it as holding the Presidency, then if you use employment as your index of economic performance and exclude recessions, then Republicans hurt the economy, and the answer to the question Is the US economy affected by whether Republicans or Democrats are in office? is “yes.” But, if you measure economic performance in terms of employment and inflation and Gross Domestic Product and stock prices, then there’s no effect on the economy at all, and so the answer to the question is “no.”

- Is it possible to find some set of conditions in which we can say that the answer to the question is “yes, the US economy is affected by whether Democrats or Republicans are in office,” and it’s the case that the economy does better when Republicans are in office? Yes! If you define “being in office” as controlling the Presidency and the House of Representatives (but not the Senate or the state governorships), and you measure economic by GDP or GDP and stock prices (but not any other combination of variables, including just stock prices), and you weight the Presidency more heavily than the other offices, and you include recessions, then the economy does better under Republicans, and the answer to the question Is the US economy affected by whether Republicans or Democrats are in office? is “yes.”

Now: how is that going to be reported in the newspapers? There are a number of possibilities–and, one important way that it won’t be reported.

- Here’s how it won’t be reported: it won’t be reported as the US economy is not affected by whether Republicans or Democrats are in office. The economist is not going to be able to publish that paper in the first place, and so the reporter is not going to come across it.

- Here’s one way that it will get reported: the US economy is affected by whether Republicans or Democrats are in office. Is that true? Under a very specific way of framing the question (we picked Republicans to look at, rather than Democrats) and a very specific way of doing the analysis (we defined “in office” a particular way, selected a specific way of defining economic performance, and made a decision about whether or not to include recessions), it certainly is true.

- Here’s another way that it will be reported: Republicans hurt/help the economy. Is it true? Yes, whichever way you state it–under a very specific definition of the question and set of decisions about how to do the analysis.

What should you conclude from this? Let me tell you some things that you should not conclude from it.

- Don’t conclude that the economist who published the paper is a liar. He/she/it didn’t make the claim that the reporter made. The economist laid out exactly the conditions under which it is/isn’t the case that the US economy looks like it’s affected by which party is in office. The reporter simplified it.

- Don’t conclude that the reporter is a liar. The reporter probably has no clue how to think about the contents of that paper critically. The reporter got the message that under certain conditions, it is the case that the US economy seems to be affected by which party is in office, and left out the “under certain conditions” part, not realizing that they are crucial to interpreting the finding.

- Don’t conclude that science is hopelessly screwed, or that statistics are not believable. That study is going to be done by lots of people, with lots of different ways of framing the question and lots of different ways of doing the analysis. Looking at those results in the aggregate, we’re going to end up with a decent understanding of under what conditions, and in what ways, the ruling political party does (or doesn’t) affect the US economy. Can the economist report all of those studies in their paper? No–they haven’t been done yet.

How does this relate back to reporting on science and health? It relates back to reporting on science and health in that we have exactly the same issues about framing questions and doing the analysis that the economists do. So do psychologists. So do historians. So do educators.

What to do? This: understand that when you read about a scientific result–or any study that involves numbers, for that matter–in the paper, it’s always more complicated–and almost always less clear-cut–than it sounds. Look at the overall picture. Ask yourself questions like the ones that we’ve asked ourselves here: which population, exactly, did the researchers look at? Out of all of the things that they could have measured, what did they measure? How many subjects did they have? You may not be able to design an experiment–really, we spend our entire careers trying to get really good at that–but, you can ask yourselves this kind of basic question about pretty much anything that you read. Try it–it’s empowering!

I fell asleep as lunch was being served. Two hours later, I woke up. I edited the paper on semantic relations and compound nouns. Then I edited the paper on inter-annotator agreement and linguistic data. I never got around to watching the TV shows. I didn’t get a blot clot!