The French 2017 presidential race is quickly coming down to a match between the far-ish right and the extreme right, it’s not clear how much longer Europe as we know it will continue to exist, and Marine Le Pen was just voted the most admired politician in France, but the main story about France in the anglophone press right now is… an explosion of the Parisian rat population.

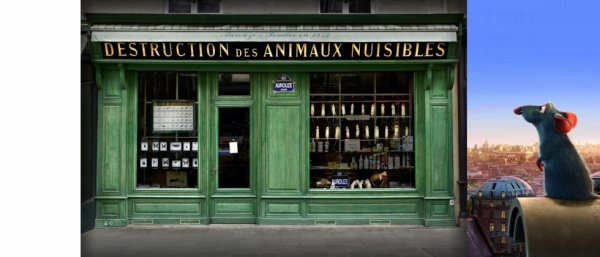

That store window in Ratatouille: it’s for real. (There’s a cool bar nearby, Le baiser salé (“The Salty Kiss”), that I stop into once in a while. I’m sparing you a photograph of the real rat window because it really is quite disgusting, and I say that as someone who once posted a picture of a grilled guinea pig here.) Friends tell me that the story has it that there is one rat for every person in Paris, but current estimates are quite a bit higher.

How would you know the size of the rat population, one way or the other? There’s a specific sampling technique that’s used to estimate the size of a population that can’t be directly observed–think about fish in a pond, or arctic ground squirrels in their little burrows, or–rats. Charming video involving goldfish crackers to be seen here.

Zipf’s Law being what it is, this brings up a linguistic oddity that I find interesting. It has to do with what’s called derivational morphology: the things that we can add to words that change their meaning or their part of speech, like the un in unlock or the ic in anemic.

French has a prefix, dé, that you can add to verbs to make them mean something like a reversal of the normal action of the verb. Alain Bentolila, in his La langue française pour les nuls (don’t mock it–it may be the best book on the linguistics of any single language that I’ve ever read) defines it and its close relatives, dés- and dis-, as contributing a meaning something like séparé de, qui a cessé de, différent. Some examples:

| visser | to screw | dévisser | to unscrew |

| voiler | to veil | dévoiler | to unveil |

| vérouiller | to bolt; to lock; to close (a brèche, in a military context) | déverrouiller | to unbolt; to unlock (a phone, a keyboard, the caps lock) |

| valoriser | to add value to, to increase the value of | dévaloriser | to devalue |

| vêtir | to dress (transitive) | dévêtir | to undress (transitive) |

This is relevant to current events because there is a set of words that have to do with removing things–mostly pestilential things, except for the last one–that have an interesting pattern with respect to this derivational prefix. To wit, I give you these examples from Bernard Fradin’s Nouvelles approches en morphologie (definitions in French when necessary, because these don’t typically show up in bilingual dictionaries)

| dératiser | to exterminate the rats in [something] (WordReference) | |

| désinsectiser | to spray [something] with insecticide (WordReference) | (I will mention here that some of the definitions of désinsectiser that I’ve come across have specified that this means to get rid of insects by using gas. I can’t find any at the moment, though.) |

| décafardiser | (not in WordReference) | détruire les cafards dans un lieu, spécialement par fumigation. (Cordial) |

| dénicotiniser | to remove the nicotine from [something] (WordReference) | |

| désodoriser | to deodorize (WordReference) | |

| dévirginiser | to deflower (WordReference) |

What’s interesting about this–a lot, actually. To wit:

- There are no corresponding forms without dé. Unlike visser/dévisser vêtir/dévêtir, we have no form of dératiser/désinsectiser/décafardiser without dé.

- These verbs seem to have both a prefix (dé) and a suffix–where does the -is- come from?

- As we will see, this gets us to an interaction that is not supposed to happen in language: between pragmatics, and morphology.

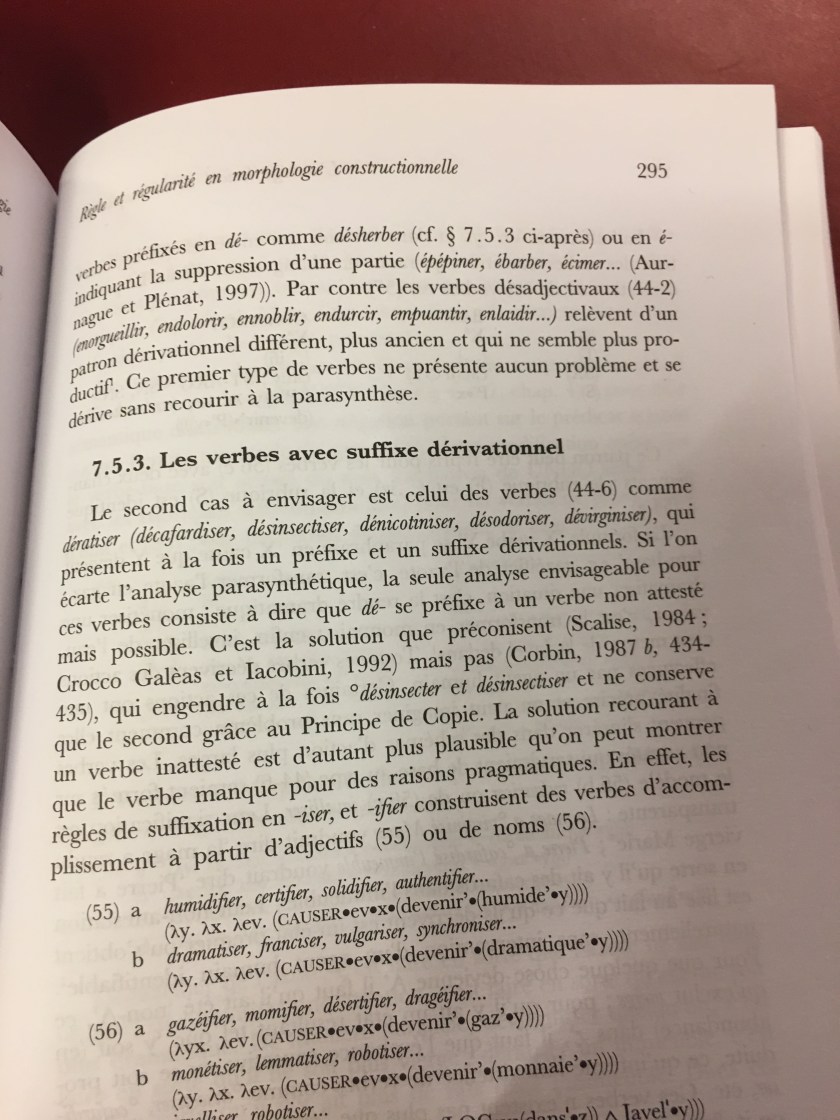

Fradin explains the pattern like this (scroll down for the translation):

The second case to consider is that of the verbs like dératiser (décafardiser, désinsectiser, dénicotiniser, désodoriser, dévirginiser) which display at the same time a derivational prefix and a derivational suffix….[T]he only analysis worth considering for these verbs is to say that here dé is affixed to a verb that is not present in the language, but is possible. The solution appealing to an unattested verb is especially plausible since we can show that the verb is missing due to reasons of pragmatics.

Fradin goes on to make the case that what we have here is a set of verbs that describe the reversal of a state that you do not create. You don’t infest something with rats, or insects, or nicotine. (Note that Molière’s Sganarelle would disagree with the notion that nicotine is something that one is infested with.) His story is that we see this bizarre combination of patterns:

- No corresponding version of the verb without dé

- There’s an -is- that doesn’t seem to have anything obvious to do with the meaning of dé

…just in the case of these verbs, in which you didn’t create the initial state of infestation.

As one of my coworkers pointed out over lunch one day: that’s not to say that you couldn’t create the initial state of infestation. He’s right: you certainly could put rats in something, or insects, or a cockroach. (In fact, that’s a famous scam, right?) It’s a nice point, because it doesn’t change the essentially pragmatic nature of the explanation for this bizarre little grouping of verbs–in fact, it highlights the involvement of pragmatics, because it argues against the possibility of an ontological explanation for this. On an ontologically-based approach, you have to have a model of reality in which it simply isn’t possible to cause something to have rats, or cockroaches, or insects, and that clearly is not the case. Rather, this is more about what’s plausible than about what’s possible. It’s not about what “is” (i.e., ontology)–it’s about what people expect to be the case. (This is a big deal (to me) because you run into people who think that the answer to every question in the world is an ontology. That doesn’t seem to be the case here. It’s also a big deal (again, to me) because the dominant school of thought in 20th-century linguistics was heavily into denying the effects of pragmatics on language. However, pragmatics appears to have a role here, if we buy Fradin’s story.)

My coworker also raised a counterargument. It’s a kind of counterargument that we really like in my line of work: positing that there is a simpler explanation for the phenomenon in question. His suggestion was that the -is- thing comes from what we call denominalization, or turning nouns into something else–in this case, a verb. (You can find a discussion of nominalization–turning a verb into a noun–here.) I don’t buy the adequacy of this hypothesis, because we can find so many French verbs that are pretty clearly denominalized–that is, derived from a noun–but don’t have the -is-. Some examples:

| dérater | Débarrasser une personne ou un animal de l’organe appelé Rate. Il se disait des Chiens à qui l’on faisait cette opération pour les rendre, croyait-on, plus agiles à la course. (L’appli Larousse Dict-français-français) | “To remove from a person or an animal the organ called Rate (spleen). It was said of Dogs to whom this operation was done in order to make them, it was thought, faster at racing.” |

| dévisser | to unscrew | ..from visser, to screw, from la vis (screw, and you pronounce the s) |

| déclouer | Détacher, défaire ce qui est fixé par des clous. (L’appli Trouve-mot) | ..from clouer, to nail, from le clou, nail |

I especially like the contrast between dérater and dératiser. The semantics of both of them involves changing the state of something (linguists are heavily into the changing of states), and they both involve changing a state that you didn’t create. So, why no -is- in dérater? If we asked Fradin, he would be likely to point out that the verbs that he mentions–that is, the ones with dé and -is–all make reference to changing a state that is in some sense noxious. In contrast, having a spleen is not something that you would think of as noxious, and so dérater–the removal of the spleen–doesn’t get the -is- part. (The technical term is morpheme.)

Now, I’ve been sorta defending Fradin here, but: I hate this kind of argument in linguistics, where you’re basically arguing on the basis of examples and counterexamples. I’m aware of the venerable history of this form of rhetoric in theoretical linguistics, but I also am more and more aware–as is much of the field–that science in general, and linguistics in particular, is less often about always and never than it is about tendencies in populations. If you look at tendencies in the population of French verbs about changing states, you can notice a group of verbs that shares a particular “behavior” (mucking about with both dé and -is-) and a particular meaning (changing a noxious state that you didn’t create). But, there are other verbs that have the dé-is- pattern that involve a change of state, but don’t involve a noxious condition–Friden himself gave us the example of dévirginiser, which I passed on to you in the second table above–and as far as I know, there’s nothing noxious about virginity in the Francophone world. Furthermore, there are:

- …verbs that have to do with changing a noxious state that you didn’t create, but have a different morphological structure that doesn’t involve dé or -is-: to delouse, which is épouiller, and likewise for to de-flea: épucer or, again, épouiller.

- …verbs with pretty much the same semantics that do take dé, but don’t take -is-. In particular, dévirginiser has another form, dépuceller, which led to a very embarrassing moment for me over lunch one day, but that’s a story for another time…

…and beyond that: who says that there are no corresponding verbs without dé, which you will recall is crucial to his pragmatically-based analysis? There are hundreds of millions of easily searchable words of naturally-occurring French-language data on the web, and I would like to see a solid effort to find those words before I bought the idea that they don’t occur in the language.

So, from my point of view, I’d want to see quantitative data. Being a minor phenomenon in a language does not by any stretch of the imagination mean that you’re not an interesting phenomenon–but, from my point of view, part of understanding anything linguistic is understanding the distribution of the phenomenon.

The mayor’s office launched a deratization campaign last month, and the story seems to have fallen out of the news. My strolls across the city haven’t run into any of the closed-off parks that you might have read about. I still stick my bread in the microwave before I go to bed at night–but, I always have. I hate rats.

English notes

rats! is a very mild way of expressing unhappy surprise. When I say “very mild,” I mean that you could say this in front of your grandmother.

- “Oh, rats!” I couldn’t find it. I had copies of other stories and poems that I’d written in the past, but couldn’t find this particular one. (Marcus Mebes, Rats! And other frustrations)

rat: an informer. This is slang.

- That Richard’s been badmouthing me to the boss behind my back; he’s a rat. Ce Richard dit du mal de moi au patron derrière mon dos ; c’est une ordure. (WordReference.com)

- We’ve used the term “rat” to refer to an informer since approximately 1910. (Mentalfloss.com)

to not give a rat’s ass: to not care (about some fact).

- I don’t give rats ass, my niece and her boyfriend met in church but she a hoe. (Twitter, in response to a tweet asking Guys!! Can you marry a girl you met at a Club? Not standard English, obviously (I don’t give rats ass, she a hoe).)

I first heard about the 9/11 attacks while sitting in my office. I’d just eaten my peanut butter sandwich–3 hours before lunch. Crap. My wife called: a plane had flown into one of the World Trade Center towers. Private plane? Airliner? Accidentally? On purpose? No one knew. Soon she called back: the other tower had been hit, too.

I first heard about the 9/11 attacks while sitting in my office. I’d just eaten my peanut butter sandwich–3 hours before lunch. Crap. My wife called: a plane had flown into one of the World Trade Center towers. Private plane? Airliner? Accidentally? On purpose? No one knew. Soon she called back: the other tower had been hit, too.