For the third day of National Poetry Month, here is more of the gentle humor of Henry Reed. This version of Movement of bodies, published in 1950, comes from the Sole Arabian Tree web site, where you can find a recording of Henry Reed reading the poem.

LESSONS OF THE WAR

III. MOVEMENT OF BODIES

Those of you that have got through the rest, I am going to rapidly

Devote a little time to showing you, those that can master it,

A few ideas about tactics, which must not be confused

With what we call strategy. Tactics is merely

The mechanical movement of bodies, and that is what we mean by it.

Or perhaps I should say: by them.

Strategy, to be quite frank, you will have no hand in.

It is done by those up above, and it merely refers to,

The larger movements over which we have no control.

But tactics are also important, together or single.

You must never forget that, suddenly, in an engagement,

You may find yourself alone.

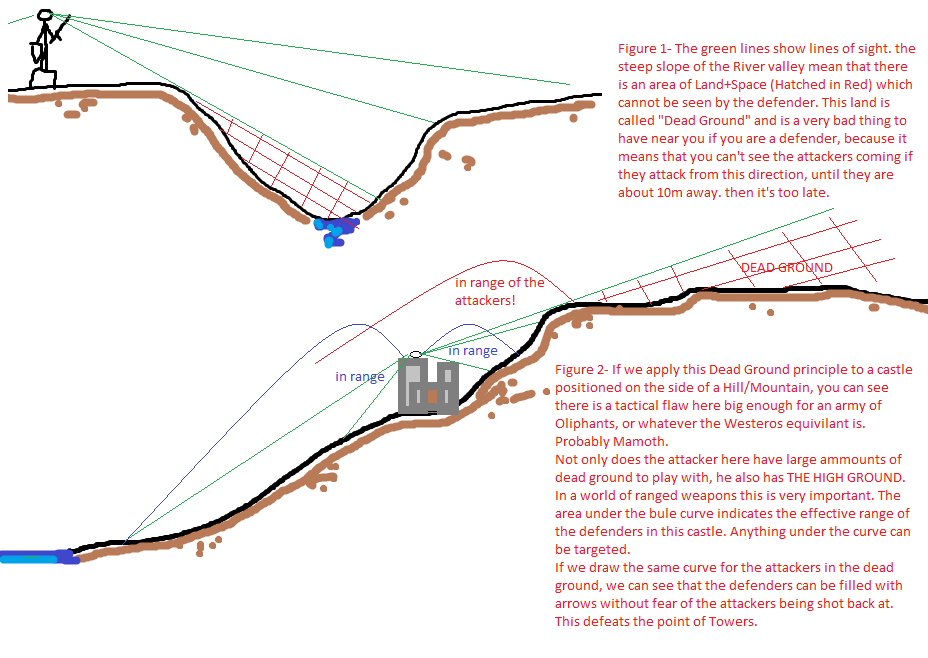

This brown clay model is a characteristic terrain

Of a simple and typical kind. Its general character

Should be taken in at a glance, and its general character

You can, see at a glance it is somewhat hilly by nature,

With a fair amount of typical vegetation

Disposed at certain parts.

Here at the top of the tray, which we might call the northwards,

Is a wooded headland, with a crown of bushy-topped trees on;

And proceeding downwards or south we take in at a glance

A variety of gorges and knolls and plateaus and basins and saddles,

Somewhat symmetrically put, for easy identification.

And here is our point of attack.

But remember of course it will not be a tray you will fight on,

Nor always by daylight. After a hot day, think of the night

Cooling the desert down, and you still moving over it:

Past a ruined tank or a gun, perhaps, or a dead friend,

In the midst of war, at peace. It might quite well be that.

It isn’t always a tray.

And even this tray is different to what I had thought.

These models are somehow never always the same: for a reason

I do not know how to explain quite. Just as I do not know

Why there is always someone at this particular lesson

Who always starts crying. Now will you kindly

Empty those blinking eyes?

I thank you. I have no wish to seem impatient.

I know it is all very hard, but you would not like,

To take a simple example, to take for example,

This place we have thought of here, you would not like

To find yourself face to face with it, and you not knowing

What there might be inside?

Very well then: suppose this is what you must capture.

It will not be easy, not being very exposed,

Secluded away like it is, and somewhat protected

By a typical formation of what appear to be bushes,

So that you cannot see, as to what is concealed inside,

As to whether it is friend or foe.

And so, a strong feint will be necessary in this, connection.

It will not be a tray, remember. It may be a desert stretch

With nothing in sight, to speak of. I have no wish to be inconsiderate,

But I see there are two of you now, commencing to snivel.

I do not know where such emotional privates can come from.

Try to behave like men.

I thank you. I was saying: a thoughtful deception

Is always somewhat essential in such a case. You can see

That if only the attacker can capture such an emplacement

The rest of the terrain is his: a key-position, and calling

For the most resourceful manoeuvres. But that is what tactics is.

Or I should say rather: are.

Let us begin then and appreciate the situation.

I am thinking especially of the point we have been considering,

Though in a sense everything in the whole of the terrain,

Must be appreciated. I do not know what I have said

To upset so many of you. I know it is a difficult lesson.

Yesterday a man was sick,

But I have never known as many as five in a single intake,

Unable to cope with this lesson. I think you had better

Fall out, all five, and sit at the back of the room,

Being careful not to talk. The rest will close up.

Perhaps it was me saying ‘a dead friend’, earlier on?

Well, some of us live.

And I never know why, whenever we get to tactics,

Men either laugh or cry, though neither is strictly called for.

But perhaps I have started too early with a difficult task?

We will start again, further north, with a simpler problem.

Are you ready? Is everyone paying attention?

Very well then. Here are two hills.

English notes

This poem is full of delightful plays on multiple meanings of words, most of which I’ll skip to focus on the lexical field of geographic terms. Reed uses a bunch of terms that refer to elements of topography (Merriam-Webster: the art or practice of graphic delineation in detail usually on maps or charts of natural and man-made features of a place or region especially in a way to show their relative positions and elevations) as metaphors for a woman’s body. Many of these are terms that a typical native speaker (including myself) wouldn’t necessarily be able to define specifically, although I would guess that most people would at least know that they refer to elements of a terrain, and might even be able to group them into two classes: ones that refer to elevations (high points), and ones that refer to depressions (Merriam-Webster: a place or part that is lower than the surrounding area : a depressed place or part : hollow ). I’ll split them out in that way, then follow them with a few miscellaneous terms. (All links to Merriam-Webster are to the definition for that word.) For a reminder, here’s a paragraph from near the beginning of the poem:

Here at the top of the tray, which we might call the northwards,

Is a wooded headland, with a crown of bushy-topped trees on;

And proceeding downwards or south we take in at a glance

A variety of gorges and knolls and plateaus and basins and saddles,

Somewhat symmetrically put, for easy identification.

And here is our point of attack.

Elevations

knoll: Merriam-Webster: a small round hill : mound. The term grassy knoll, a small hill covered with grass, is closely associated with the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, particularly with conspiracy theories about it.

headland: Merriam-Webster: a point of usually high land jutting out into a body of water : promontory

plateau: Merriam-Webster: a usually extensive land area having a relatively level surface raised sharply above adjacent land on at least one side : tableland

Depressions

gorge: Merriam-Webster: a narrow passage through land; especially : a narrow steep-walled canyon or part of a canyon

basin: Merriam-Webster: a large or small depression in the surface of the land or in the ocean floor. As I speak a bit of French, it’s difficult not to make the association here with le bassin, the pelvis.

saddle: Merriam-Webster: a ridge connecting two higher elevations; a pass in a mountain range. In English, this has the same connections with sex as it does in French: J’en ai-t-y connu des lanciers, // Des dragons et des cuirassiers // Qui me montraient à me tenir en selle // A Grenelle!

Others

wooded: Merriam-Webster: covered with growing trees

engagement: In the context of the poem, the most obvious meaning is the military one of a hostile contact between enemy forces (Merriam-Webster). Presumably Reed is also playing here on the more commonly-used meaning of a commitment to marriage (my best guess on all of the crying trainees).

tactics versus strategy: tactics are short-term–a tactical nuclear weapon is one that you would use on the battlefield. (Not very fun to think about, is it? When I tell people that some aspects of the peacetime military seem kinda silly and they ask me for examples, I always tell them about our “what to do in case of nearby nuclear weapon explosion” drills.) In contrast, strategic nuclear weapons are meant for the bigger picture–the stuff that you would use to hammer the other guy’s country in such a way that he becomes unable to continue fighting at all. My tactics in my professional life mostly consist of making schedules to ensure that I don’t miss deadlines, while my strategy is the set of papers that I plan to publish in the next few years. From the poem:

Strategy, to be quite frank, you will have no hand in.

It is done by those up above, and it merely refers to,

The larger movements over which we have no control.

But tactics are also important, together or single.

You must never forget that, suddenly, in an engagement,

You may find yourself alone.