You’d think that when people in my line of work–research–sit around the hotel bar at a conference swapping war stories, we’d mostly be complaining about the crappy state of research funding, pesky deans, and flying economy class–and we do. But, what we complain to each other about the most is how much reviewing we have to do. Peer review–the evaluation of articles by your fellow academics for suitability for publication–is a big part of being an academic. One of the things that makes science an exciting thing to be doing right now is that it’s booming–the amount of productivity in the world of research right now is enormous. (Booming explained in the English notes below.) In my field alone–biomedical language processing–the number of conferences has grown enormously since I got started in the field, and it shows no signs of slowing down. The thing is: lots of research activity means lots of papers being produced, and lots of papers being produced means lots of papers to review. Lots of papers. Most academic conferences in any field take place either during the summer or in early January–the easiest times to travel without having to miss the classes that you’re usually teaching. Consequently, there are a couple of periods during the year when you get slammed with a lot of reviewing requests all at once. This is on top of the constant flow of journal articles, which can get submitted at any time, plus grant reviews, which come in thrice-a-year waves themselves. It can get pretty overwhelming.

Reviewing is a big responsibility–a reviewer’s comments and recommendations about acceptance affect the progress of science, and the progress of people’s careers, too. That makes it an opportunity to make a real contribution to your community. There are some good things about the fact that you’re being asked to do it. If you’re getting invited to review, it’s a sign that your peers hold your expertise in high enough esteem that they think it’s OK to entrust you with a job that is of some importance. Reviewing is also part of how you stay on top of what’s hot and exciting in your field. If you can keep that it mind as you stare at a pile of papers on a beautiful Sunday afternoon when you’d rather be sitting on the back porch with a beer and a trashy novel, it certainly helps.

There are a lot of approaches to writing a review. I don’t claim to have the perfect one, and the specifics of how I structure a review have certainly changed over the years. However, there are a few such structures that clearly make sense, and that you can apply secure in the knowledge that they won’t leave the authors angry and frustrated or the editors that have to pass those reviews along to the authors feeling embarrassed, or worse. Here’s one structure to think about. It starts with an overview of the paper that you’re reviewing.

All quotes are from reviews of my own papers. I was either the first author or the “senior author” (in my field, that means the person who directed the research, typically coming up with the idea and then supervising the design of the experiments and the writing of the article) of the work.

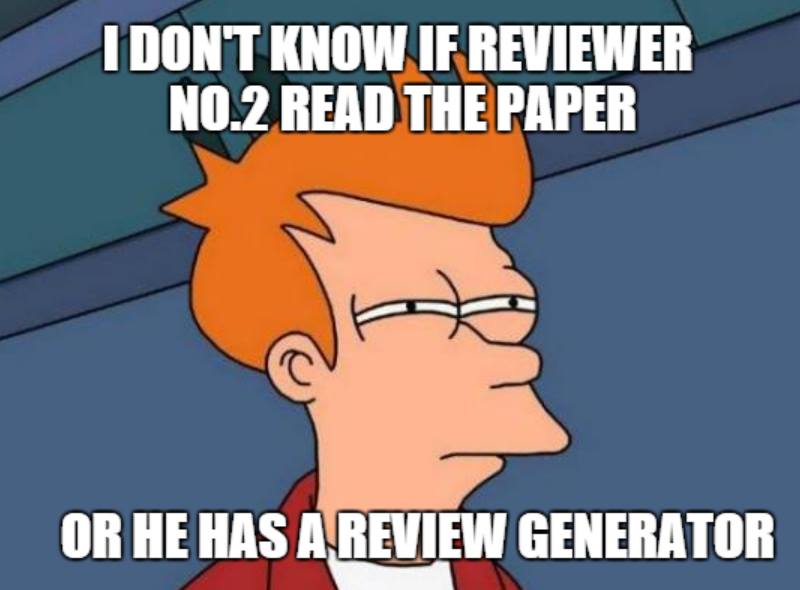

A little overview of the paper at the beginning of your paper serves a couple purposes. One is to reassure the author that you read the paper with attention. This may sound obvious, but unfortunately, it’s not that uncommon to get a review back and wonder whether the reviewer really read it. A research paper typically represents around a year’s work, and it’s Here’s a beautiful example of a summary of the paper at the beginning of a review:

This work presents a novel study of inter-annotator agreement when labelling semantic relations in compound nouns. The authors asked two annotators to annotate such relations in a subset of 101 Gene Ontology concepts according to two commonly used relation sets, namely the Generative Lexicon and the Rosario and Hearst sets, respectively with five and 38 relations. Cohen’s Kappa factor and F1-score are reported for both tasks, with a maximum of k = 0.774 and F1 = 0.90 in a relaxed evaluation of the Rosario and Hearst relation set.

What’s so nice about it? Everything. It summarizes:

- What the paper is about (This work presents a novel study of inter-annotator agreement when labelling semantic relations in compound nouns),

- …what was done, and with what data (The authors asked two annotators to annotate such relations in a subset of 101 Gene Ontology concepts according to two commonly used relation sets, namely the Generative Lexicon and the Rosario and Hearst sets, respectively with five and 38 relations),

- …and what the authors found (Cohen’s Kappa factor and F1-score are reported for both tasks, with a maximum of k = 0.774 and F1 = 0.90 in a relaxed evaluation of the Rosario and Hearst relation set).

Here’s another one that was really nicely done. The reviewer covered pretty much the same things:

The manuscript studied the ability of humans to label the semantic relations between the elements of noun compounds. Two annotators, one with a BS and the other one as a cardiovascular technologist did the annotations. The sample annotation terms were defined based on the GO. The test relations are the Generative Lexicon relations and the Rosario and Hearst relations. The F-measure and the Cohen’s Kappa value are used to measure the inter-annotator agreements. The results showed fairly high agreement even with very minimal guidelines and no real-training.

…which is to say:

- what the paper is about (The manuscript studied the ability of humans to label the semantic relations between the elements of noun compounds),

- …what was done, and with what data (Two annotators, one with a BS and the other one as a cardiovascular technologist did the annotations. The sample annotation terms were defined based on the GO. The test relations are the Generative Lexicon relations and the Rosario and Hearst relations. The F-measure and the Cohen’s Kappa value are used to measure the inter-annotator agreements),

- …and what the authors found (The results showed fairly high agreement even with very minimal guidelines and no real-training).

This paper investigates on the assumption that inter-annotator agreement (IAA) can be used as an upper bound for NLP systems performance. The authors make a review of the literature to extract papers that support this assumptions and papers that instead have found opposite results, concluding that there are several works where NLP systems have demonstrated to outperform inter-annotator agreement. The authors also correlate IAA with the performance of the systems as reported on the papers, finding that in general there is a positive correlation among the two.

This very nice summary doesn’t talk about what was done, or to what data, but it goes much more than the preceding ones into what the authors found, and the reviewer’s assessment of whether or not, and why, that matters.

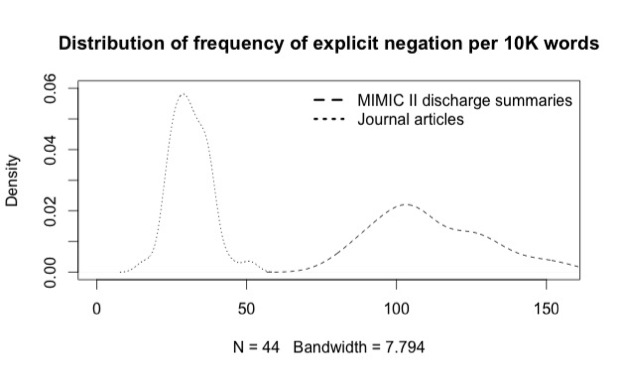

The manuscript titled “Translational morphosyntax: Distribution of negation in clinical records and biomedical journal articles” discusses differences in the use of negation between journal articles and clinical notes. Clinical notes are found to be much more explicit in their use of negation than journal articles, while journal articles use morphological negation significantly more often than clinical notes. The results have significant impact on mining clinical notes and combining information in clinical notes with background information found in literature.

This one takes the approach of the first summaries that we read–what the paper is about, what was done and with what data, and what was found:

The authors present a study on the distribution of negation (explicit at the syntactic/lexical level and morphological at the sub-word level) in two document types (clinical text and scientific journal articles). They investigate whether there are significant differences in the distribution of these two levels of negation between the two types of texts. Distributions are calculated from clinical progress notes from the MIMIC II corpus and the CRAFT corpus. The main findings are that explicit negations are more prevalent in clinical text, while morphological negation is more prevalent in scientific text.

Now, I must say: the preceding introductions are exceptionally well done. The following is more typical for an introduction to a review–if it has one at all:

The authors compare incidence of two types of negations. They use notes on the status of patients in the Intensive Care Unit and compare these with scientific journal articles on mouse genomics.

Here’s the thing: the one that you just read is enough to make it clear that you read the article and bothered to figure out what it’s about. Sounds pretty goddamn basic–but, unfortunately, it’s not. Not having a summary at the beginning of a review that you’re writing really isn’t a problem if you write a well-justified review–but, if you do a shoddy job that leaves the authors wondering whether or not you read the paper with the appropriate level of care, it’s going to piss them off; if they complain to the editor, it’s going to piss off the editor, too, as well as embarrassing them for not having caught your crappy work; and you should feel guilty. Putting a summary of the paper at the beginning of your review doesn’t just reassure the authors–it’s a good way for you to verify to yourself that you actually do have a good grasp of what’s going on in the paper. One final note on this: if the paper is so badly written that you can’t actually tell what’s going on in it, it’s totally appropriate to say so, explicitly, and this is the point in the review where you should say it–in the introduction to your review. Summarize what you can, and be explicit about what parts of the paper weren’t intelligible enough to summarize.

Since I started this piece with a description of complaining, I’ll close with an attempt at attitudinal adjustment. Ashley ML Brown on her blog:

Reviewing the work of your peers should be pleasurable. Don’t laugh. I am serious. It should be a chance to see what others in your field are doing, a chance to read cutting edge research, and a chance to share your expertise (what good is knowledge if you don’t use it?)

English notes

booming: this word has at least two senses (meanings). In the blog post, it shows up with Merriam-Webster‘s sense number 2: growing or expanding very quickly. Here’s how I used it: . One of the things that makes science an exciting thing to be doing right now is that it’s booming–the amount of productivity in the world of research right now is enormous.

There’s another common sense of this word, which Merriam-Webster gives as making a loud deep sound. Their example his booming voice is totally natural.

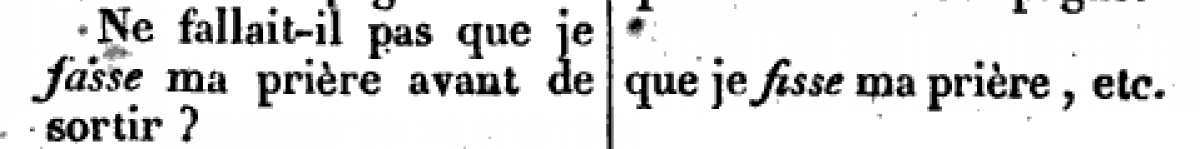

French notes

l’évaluation par les pairs: peer review.