Notre Père qui êtes aux cieux

Restez-y

Et nous nous resterons sur la terre

Qui est quelquefois si jolie

Avec ses mystères de New York

Et puis ses mystères de Paris

Qui valent bien celui de la Trinité

Avec son petit canal de l’Ourcq

Sa grande muraille de Chine

Sa rivière de Morlaix

Ses bêtises de Cambrai

Avec son Océan Pacifique

Et ses deux bassins aux Tuilleries

Avec ses bons enfants et ses mauvais sujets

Avec toutes les merveilles du monde

Qui sont là

Simplement sur la terre

Offertes à tout le monde

Éparpillées

Émerveillées elles-mêmes d’être de telles merveilles

Et qui n’osent se l’avouer

Comme une jolie fille nue qui n’ose se montrer

Avec les épouvantables malheurs du monde

Qui sont légion

Avec leurs légionnaires

Aves leur tortionnaires

Avec les maîtres de ce monde

Les maîtres avec leurs prêtres leurs traîtres et leurs reîtres

Avec les saisons

Avec les années

Avec les jolies filles et avec les vieux cons

Avec la paille de la misère pourrissant dans l’acier des canons.

Our Father who art in heaven

Stay there

And we’ll stay here on Earth

Which is sometimes so pretty

With its mysteries of New York

And then its mysteries of Paris

Which are worth every bit as much as the Trinity

With her little Canal of the Ourcq

Her Great Wall of China

Her Morlaix River

Her stupidities of Cambrai

With her Pacific Ocean

And her two fountains of the Tuileries

With her good children and her bad apples

With all of the wonders of the world

That are here

Just right here on Earth

Free to all the world

Scattered

In wonder over being such wonders

And who don’t dare admit it to themselves

Like a beautiful naked girl who doesn’t dare show herself

With the dreadful calamities of the world

Which are legion

With its legionnaires

With its torturers

With the masters of this world

The masters with their priests, their traitors, and their mercenaries

With the seasons

With the years

With the pretty girls and with the old jerks

With the straw of misery rotting in the steel of the cannons.

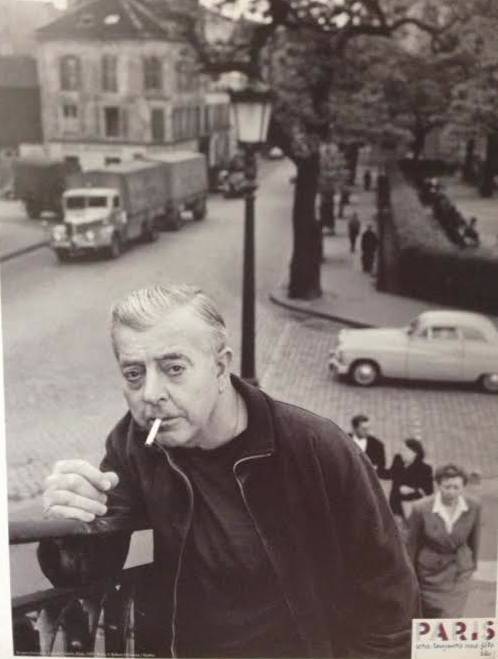

As someone smarter than me first observed: love poetry tends to be pro-love, while war poetry tends to be anti-war. This one is by Jacques Prévert, a veteran of the First World War who was a major figure in French poetry, theater, and cinema after the Second World War. There’s a lot of love in his poetry, a lot of Paris in his poetry–and a lot of war. Like almost everyone who has ever been in a war, he hated it. This poem follows a common pattern of Prévert’s war poetry: start off with something sweet and funny, and then…the war comes along.

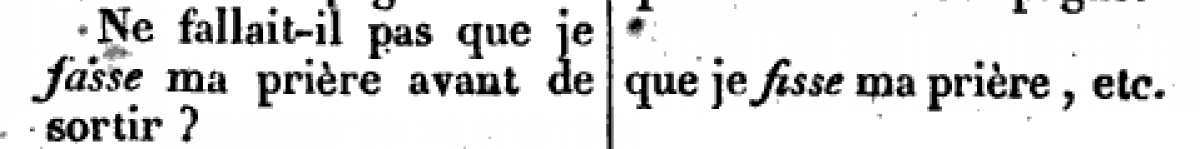

Reading Prévert was the first thing that ever really made me grasp “the impossibility of translation.” Most good poets will, at some point or another, play around with the sounds of the language; most of the time, I don’t notice it. Prévert pushes it far enough for even me to get it. For example, here are my second-favorite lines of the poem:

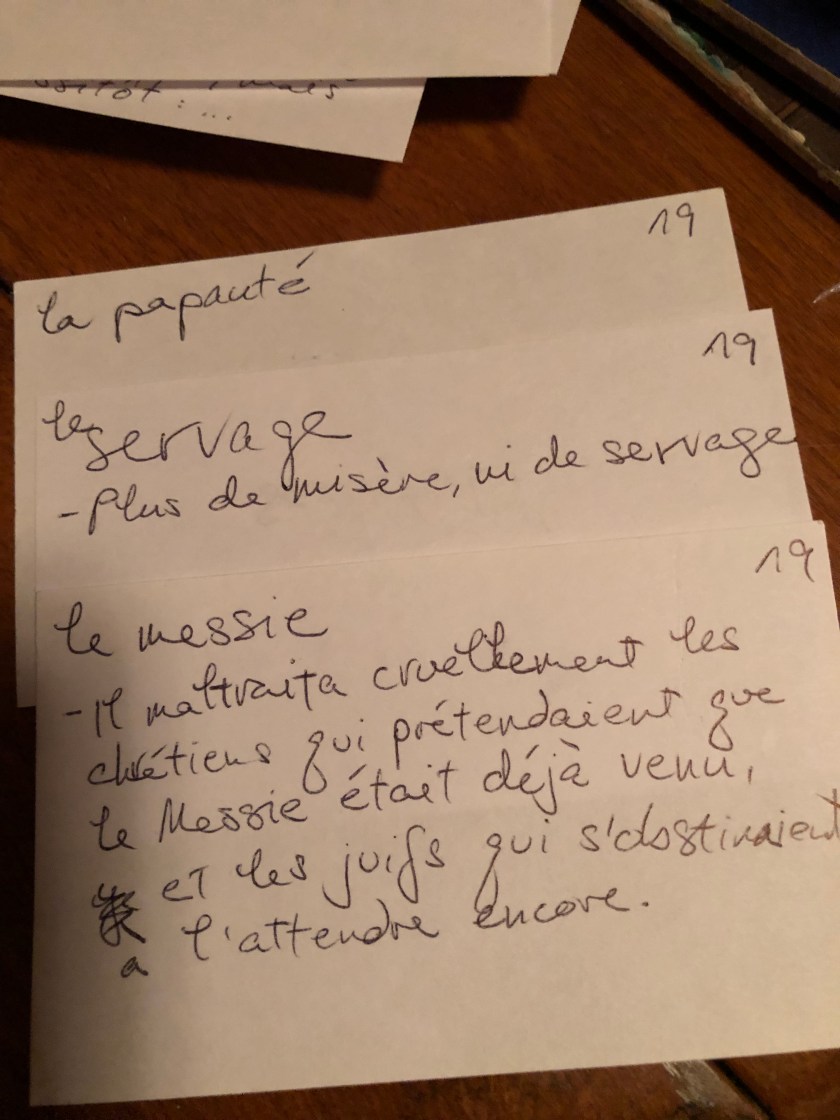

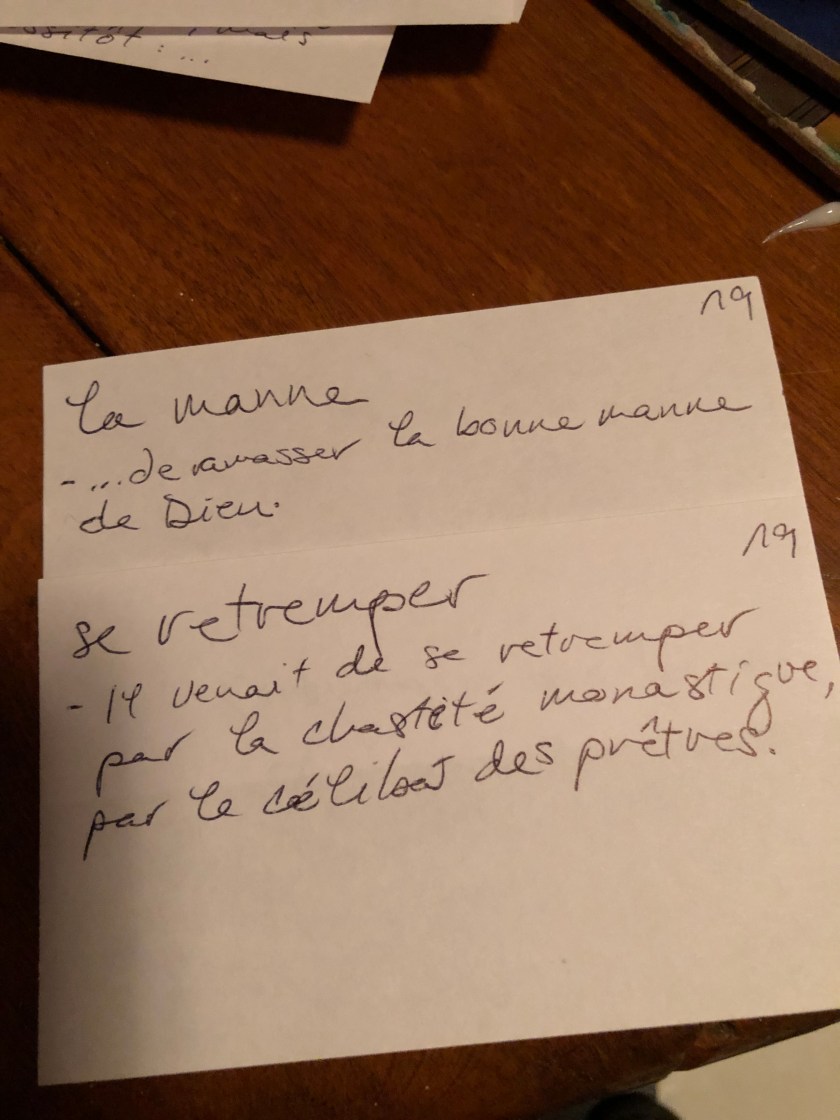

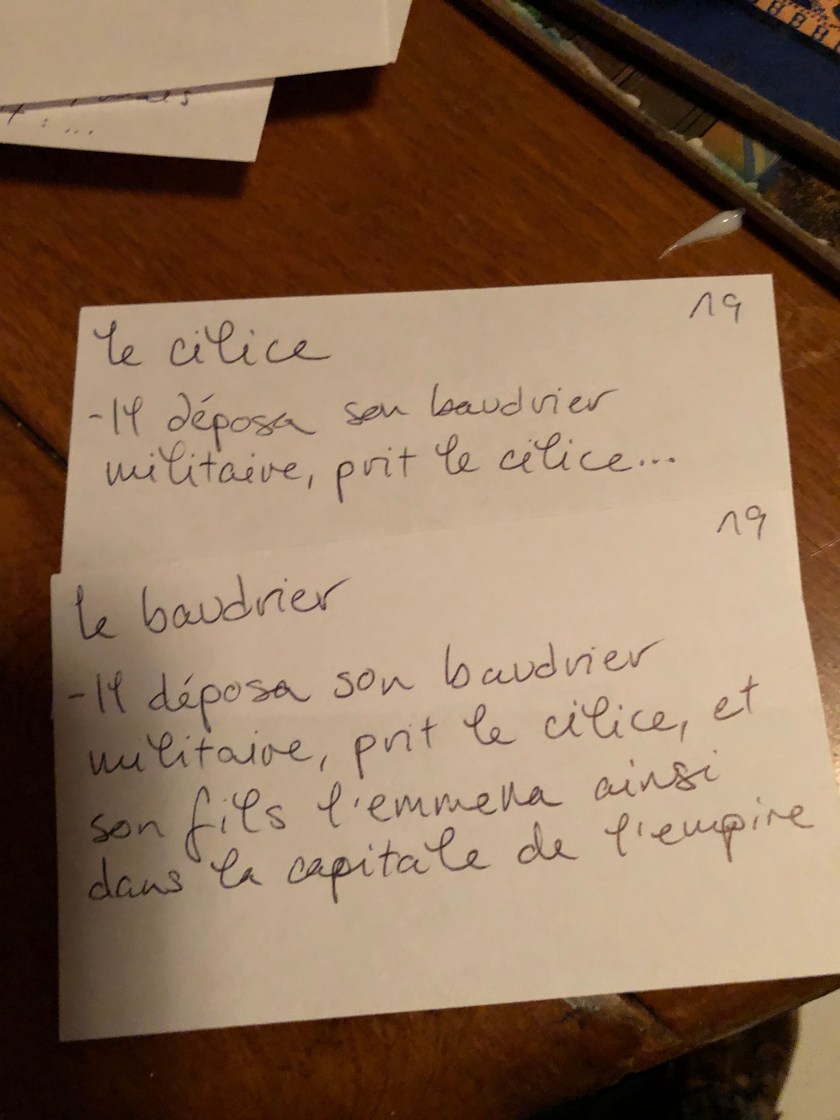

Avec les maîtres de ce monde

Les maîtres avec leurs prêtres leurs traîtres et leurs reîtres

The bolded words are all rhyming monosyllables. I’ll just note in passing that when spoken, the lines have the effect of someone beating on a drum. I’ll just note in passing that there is no way to translate that while maintaining that beautiful rhythm, that repetition of the internal rhyme. I’ll just note in passing that as someone who loves the circumflex accent about as much as anything else he loves about the French language, the fact that each of those words has one is… a joy. But, I’ll dwell a bit more on the vocabulary.

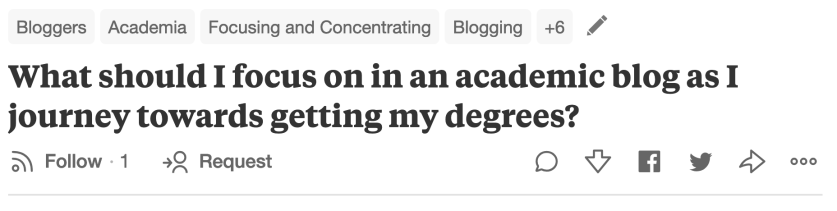

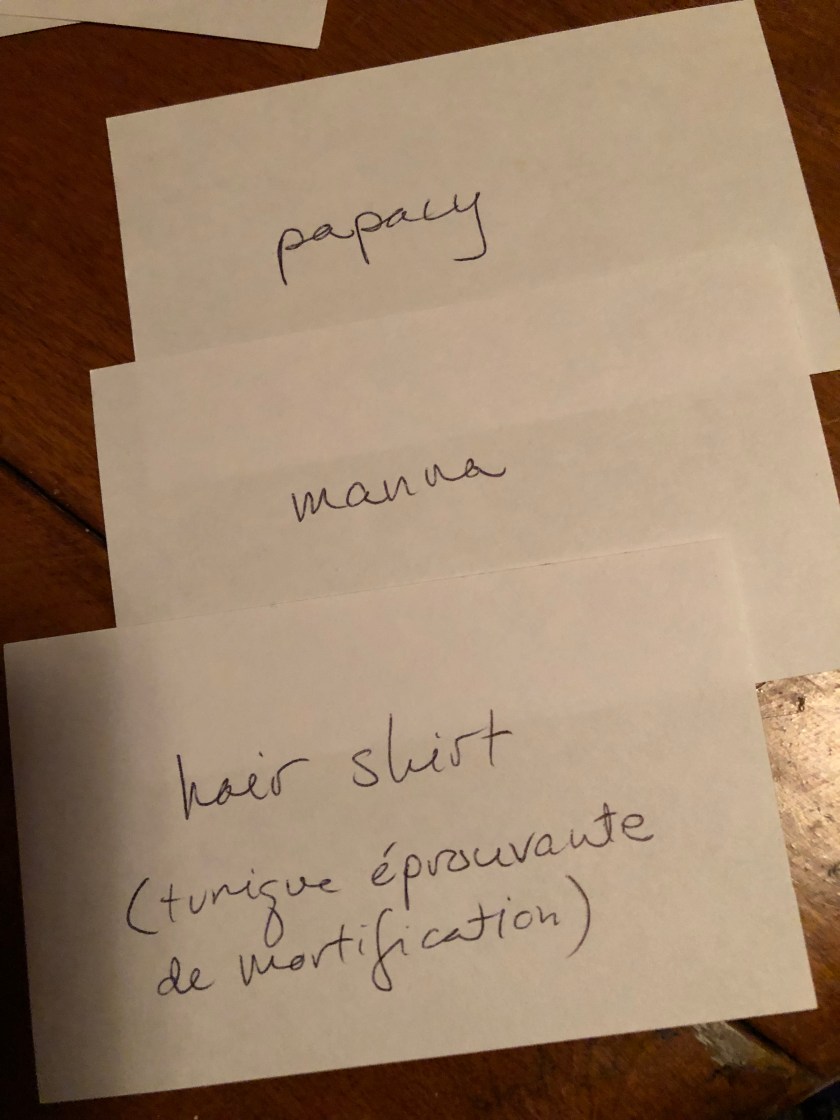

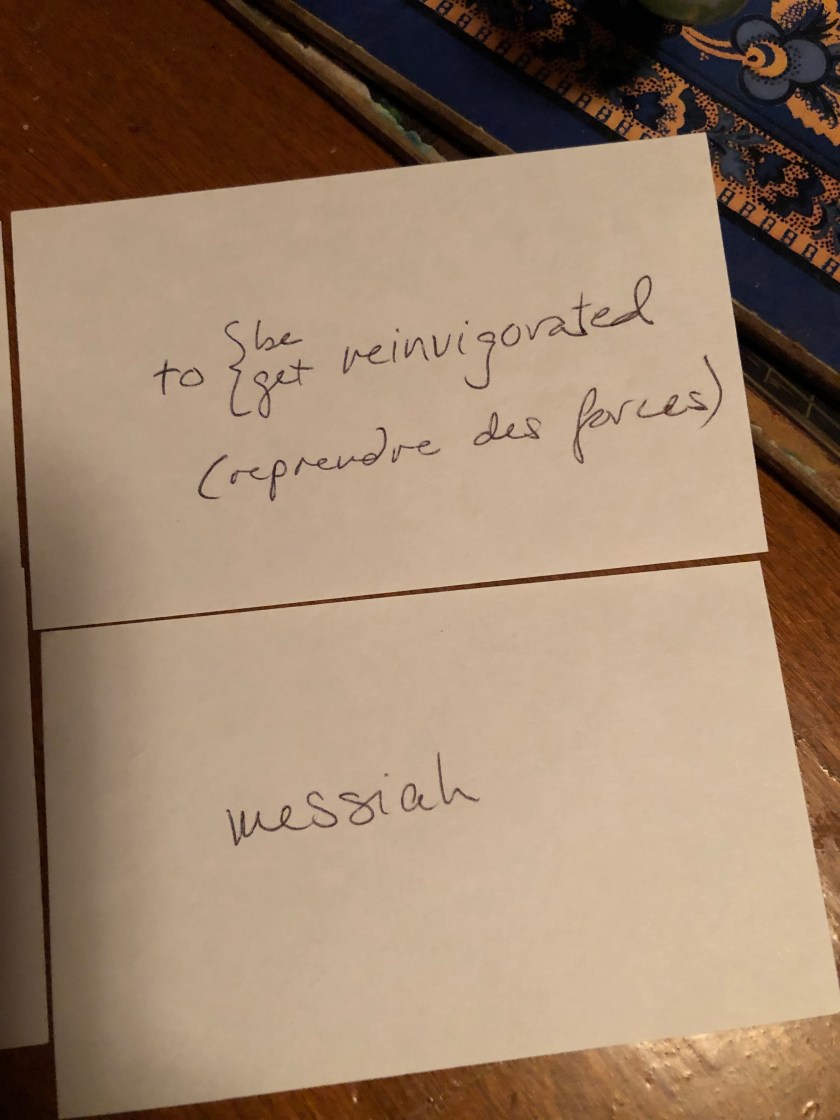

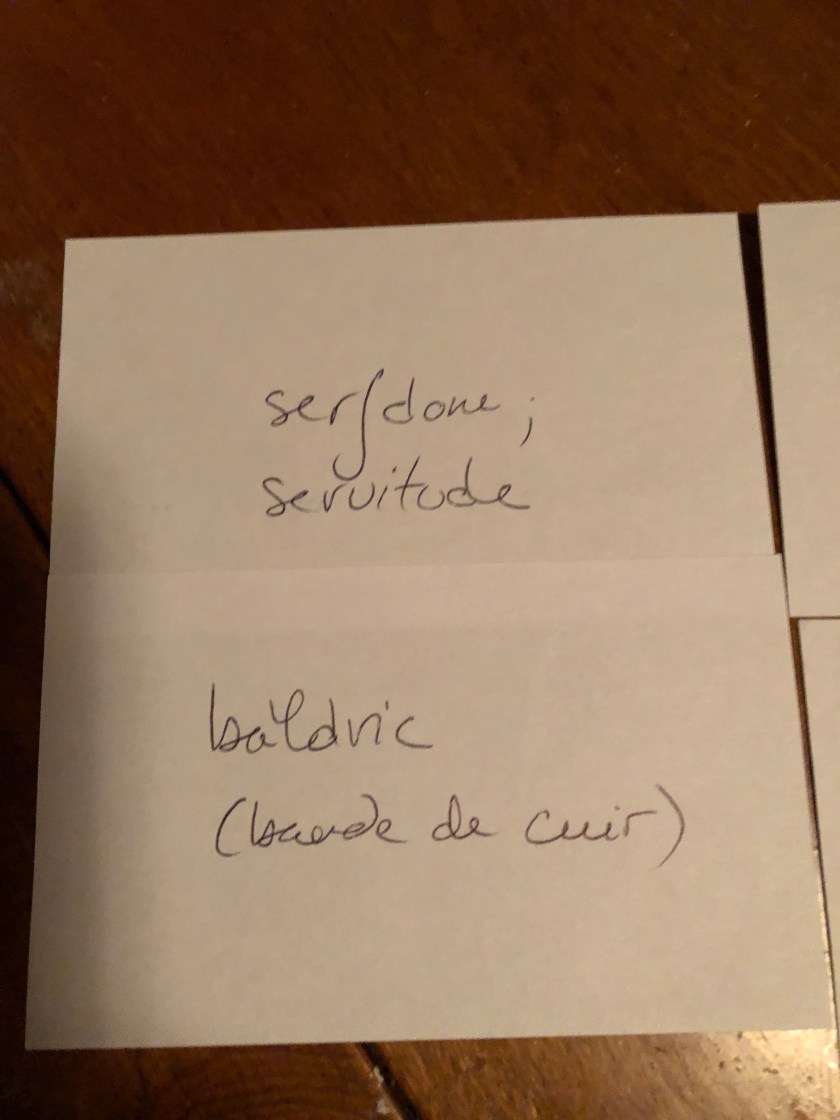

Le reître is obscure enough that even educated French people don’t necessarily know it. Here’s what I found when I looked it up:

HIST. MILIT. Cavalier allemand mercenaire au service de la France aux xveet xvies. Vainement aussi il [le roi Henri III] tenta, en négociant, d’arrêter une armée allemande, vingt mille reîtres en marche pour rejoindre les rebelles de l’ouest et du Midi (Bainville, Hist. Fr., t. 1, 1924, p. 179).

Translation: German mercenary in the service of France in the 15th and 16th centuries. (I believe it’s also a regionalism meaning something like an old (retired?) soldier. Being a fat old bald guy who spent 9.5 years in the service of his country: I can dig it.)

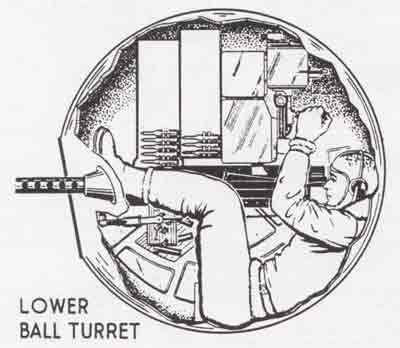

As an American, I find the word reître interesting because it opens a window on something quite topical: the US military’s low level of support for Trump. He’s at under 50% approval among service members as a whole, and at 30% in the officer ranks. Why? Lots of reasons, some of which I’ve written about elsewhere. The relevant one in this case: conscience.

When you join the American military, you take an oath. The oath is not to protect the country, or the president, and certainly not to protect the flag. (Has anyone ever been stupid enough to kill for a piece of cloth?) The oath is to protect the Constitution.

What’s the Constitution all about? Basic principles. Principles in the sense of what is right, and what is wrong. Note what is not in there: money.

We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.

Let’s go back to the definition of reître now:

German mercenary in the service of France in the 15th and 16th centuries.

Is there anything wrong with being German? No. Is there anything wrong with being in the service of France? No. Is there anything wrong with being a mercenary? Absolutely.

Being in the American military does not have much to do with the question What would you die for? That’s straightforward: in the American military, you might die if your boss makes a stupid mistake, but if your boss doesn’t make a stupid mistake, you’re probably coming home again. The question, then, is this: What would you kill for? The answer to that: basic principles. Justice, liberty, tranquility. Notice what’s not on that list: money. The American warfighter is not a mercenary.

How does that relate to President Donald J. Trump? Because he–never a fighting man himself–seems to think that we do, in fact, kill for money. Here are the kinds of quotes that make an American military person think that their Commander in Chief should not, in fact, be their Commander in Chief. They are President Trump talking about American commitments of military troops to our allies:

…why are we doing this all free?…They should be paying us for this.

President Donald J. Trump, excerpted from a Fox News interview with Greta van Susteren on April 5th, 2013: response to a question on US troop commitments in South Korea.

…they have to protect themselves or they have to pay us.

President Donald J. Trump, from an interview with Anderson Cooper, quoted here.

…they [South Korea and Japan] have to protect themselves or they have to pay us. Here’s the thing, with Japan, they have to pay us or we have to let them protect themselves.

President Donald J. Trump, CNN Town Hall on March 29th, 2016, quoted here.

My 9.5 years in the US Navy ended over 30 years ago. One of my ex-military buddies is less than 30 years old. Point being: I have some personal insight into the views of American military veterans over a wide range of time. I get why the kids in the military today support President Trump at a level even lower than the general American population. I get why my military veteran friends support President Trump at a level much lower than the kids on active duty. I don’t want to get paid to kill people. What non-sociopath does?